California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier academic management journal published at UC Berkeley

by Feng Li

Image Credit | Rodion Kutsaev

The organisational change literature is dominated by two prevailing models. The punctuated equilibrium model asserts that long periods of incremental change is interrupted by brief periods of radical change. The continuous morphing model illustrates continuous radical change in nascent, rapidly evolving business environment.1

“Dynamic Capabilities and Organizational Agility: Risk, Uncertainty, and Strategy in the Innovation Economy” by David Teece, Margaret Peteraf, and Sohvi Leih. (Vol. 58/4) 2016.

“How Do Firms Adapt to Discontinuous Change? Bridging the Dynamic Capabilities and Ambidexterity Perspectives” by Julian Birkinshaw, Alexander Zimmermann, and Sebastian Raisch. (Vol. 58/4) 2016.

However, neither model could adequately explain the trajectory of organizational change observed in the competition between leading global platforms and their rising native counterparts in some large emerging markets. Based on a comprehensive longitudinal study of the competition between Amazon vs JD.Com, eBay vs Taobao (part of Alibaba), Google vs Baidu, and Uber vs Didi Chuxing in the largest digital market in the world by user numbers (China), a new spiral model of continuous change is developed. The key findings have accepted for publication in ‘Sustainable Competitive Advantages via Temporary Advantages: Insights from the Competition between American and Chinese Digital Platforms in China’ (Li, forthcoming).2

A systematic and nuanced understanding of the competition between these platforms is particularly relevant today as international technological competition intensifies, the global digital economy bifurcates, and indeed, as the global economy is under increasing geopolitical pressure to decouple. The underlying dynamics and the outcomes of the competition may fundamentally reshape international geopolitical patterns and future economic opportunities; and shine a light on how future technologies are developed and deployed, how business strategies are made and executed, and how policy and regulation are formulated and implemented across different countries and regions.

Digital platforms challenge traditional ways of thinking about strategy, and their distinctive features affect international competition differently when compared with conventional multinational firms or traditional manufacturing or product platforms. In the competition for market leadership between leading global platforms and rising native platforms in some large emerging markets, three intertwined mechanisms have often been deployed.

First, from one source of competitive advantage to another: Although competitive advantages can be derived from a firm’s market position, resource and capability, or institutional environment, it is unclear how competitive advantages from one source may lead to new competitive advantages from other sources. My research has found that some native digital platforms have effectively exploited their inherent institutional advantages based on deeper understanding of the local market, culture and other aspects of the institutional environment to overcome the strong competitive advantages of global platform leaders based on superior resource and capability and dominant market position. This allows a small number of native digital platforms to survive and grow. By improving their own resource and capability and market positions, some weaker native platforms have managed to accumulate competitive advantages from different sources, eventually reaching a critical level that triggers the network effect and the winner-takes-all market dynamic to displace the market leader.

Second, from transient advantages to sustainable competitive advantages: sustainable competitive advantages are often assumed to exist, but in the rapidly evolving digital economy, few competitive advantages are genuinely sustainable over prolonged period. In platform competition, however, sustainable advantages can be made up of an evolving portfolio of transient (or temporary) advantages over time. New transient advantages are continuously introduced before old advantages are eroded, therefore, sustainable competitive advantages can be achieved dynamically and cumulatively, eventually reaching a critical level that triggers the increasing return market dynamic and network effect to win the competition.

Third, from incremental innovations to radical innovations: while radical innovations make headlines and capture the attention of senior business leaders, such innovations are rare, hard to come by and often highly risky to implement. However, in platform competition, radical innovations do not have to be achieved in one big step. Instead, through successive incremental changes, radical innovations can be realized over time. In their competition with leading American platforms, some Chinese platforms followed a relentless cycle of imitation, iteration and innovation for their products, platforms and business models based on experimentation and user feedback. This enables some Chinese platforms to try out new ideas inexpensively. ‘If a new idea works, then scale it up quickly. If not, move onto other ideas and you have not lost anything.’ [Senior Executive from Alibaba]. The benefit from each change is often small, but over multiple iterations, radical innovations can be realized cumulatively, eventually triggering the increasing return to scale dynamic to dominate the local market.

These mechanisms are not limited to the competition between leading American platforms and rising native platforms in China. Similar trends have been observed in India and Southeast Asia, and increasingly in developed markets in Europe. These mechanisms offer plausible routes for weaker platforms to survive and thrive in competition with dominant platform leaders.

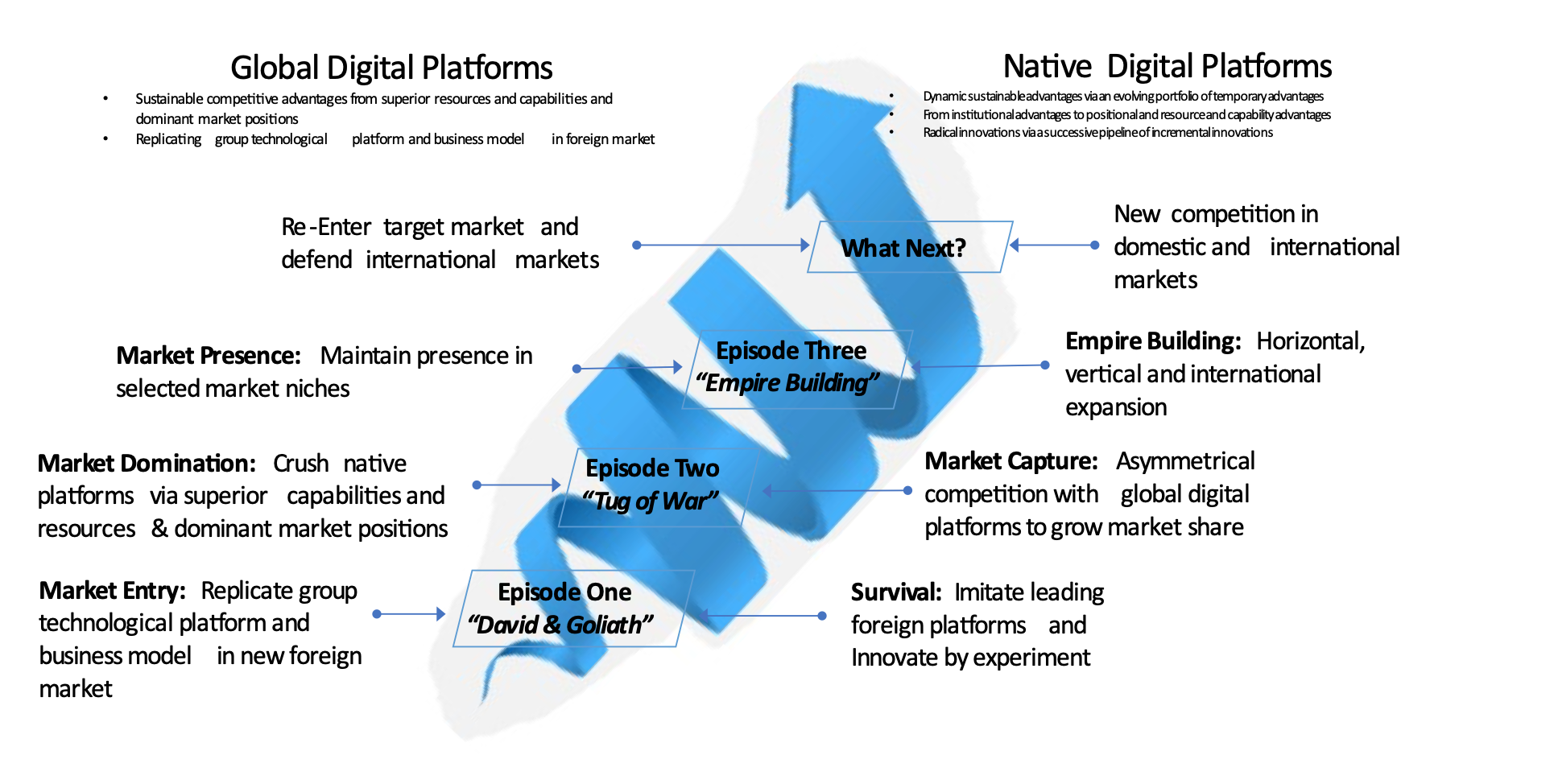

The result of the platform competition is not a punctuated equilibrium model nor a continuous morphing model of organizational change. Rather, a new spiral model of continuous change has emerged with three distinctive episodes. Unlike the punctuated equilibrium model when long periods of incremental change are interrupted by brief periods of discontinuous change, the different episodes are the result of a continuous, cumulative process. It is also different from the continuous morphing model in that the distinctive episodes – the different coils of the spiral - are clearly identifiable, with each episode calling for a distinctive strategic orientation.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, the intensity and tempo of the competition is often dictated by native platforms, leaving the dominant global platforms responding passively to different moves initiated by different challengers. The process has been described as “controlled escalation”, through which the competition spirals onward and upward into new episodes in a continuous process (Figure 1).

During the first episode, the global platform champions are often significantly stronger than native local platforms, even when the native platforms have a significant head start in the local market. Their competition can be illustrated as ‘David vs Goliath’. Some native platforms are often able to survive and grow by avoiding head-on collisions and exploiting various temporary advantages based on incremental and radical changes.

When some native platforms grow to a comparable scale as the global platform leaders in the local market, their competition evolves into the second episode characterised by ‘Tug of War’. The strategic focus of all players is on land-grabbing, as achieving a large installed base early could lead to a dominant market position. Many platforms use penetration pricing to rapidly build up an installed base in the hope of recouping early losses later through secondary revenue streams. This is largely driven by the increasing return to scale dynamic and network effect, which leads to “winner-takes-all” markets.

In the third episode, some native platforms build on the momentum to dominate the local market. Their focus shifts to ‘Empire Building’ to consolidate their local dominance. In addition to forming strategic partnerships with key service providers or via direct investment in support services, some native platforms often expand beyond their core business by investing in promising new start-ups in adjacent or new markets, and expand internationally. A particularly interesting observation is the increasing investment in asset-heavy business models by native platforms to serve as entry barriers, which diverges from the asset-light business model preferred by many global platform leaders.

It is still not clear what might happen next, but platform competition is likely to further escalate with the re-entry of global platforms in local market; and the international expansion of some native platforms into other developing and developed countries dominated by leading global platforms. The newly dominant native platform leaders in local market may experience similar disruptions from other challengers through a similar process.

The spiral model challenges traditional views that radical change does not happen slowly or cannot be accomplished gradually or piecemeal. It highlights a distinctive trajectory of organizational change in platform competition and a plausible new path that native digital platforms from large emerging markets could follow when competing with leading global platform leaders. The rapid rise of TikTok to erode the market dominance of Facebook in a number of international markets around the world suggest that no one is immune to such disruption. The spiral model of continuous change offers practical mechanisms and plausible trajectories that weaker platforms adopt to survive and thrive in competition with dominant global platform leaders.

Figure 1: A Spiral Model of Continuous Change in International Platform Competition

Source: Adapted from Li (forthcoming)

Three new insights can be drawn from this research for business leaders and entrepreneurs.

First, the new spiral model shows that competitive advantage is associated with an eclectic process of renewal based on favourable market positions, superior resources and capabilities, and familiar institutional environment. Competitive advantages from one source can be leveraged for new competitive advantages from other sources. The study also reveals the nonlinear dynamics at work in platform competition; and highlights the strategic role of temporary advantage when change and continuity are simultaneously attained. It reveals how small changes can emerge and spiral into something more significant through a cumulative process. Specific intended and unintended actions often led to other emergent changes, amplifying the initial small change into something much bigger.

Second, the new spiral model challenges the traditional linear process of strategy making and execution, as strategy is increasingly made and recalibrated through execution using emerging intelligence, particularly when both the path and destination for the platforms need to be continuously reassessed in the rapidly changing business environment.

Third, this new model exposes the limitations of traditional competitive practices, where much of the emphasis is on rivalry, head-on competition, and attack and response among players within an industry. Native digital platforms often seek victory not in one single decisive battle in a clearly defined market niche, but rather through successive incremental and radical moves designed to improve their positions gradually through a continuous process of controlled escalation, eventually winning the competition by triggering increasing return and network effect.

These new insights can help business leaders and entrepreneurs to survive and thrive in platform competition in the rapidly evolving digital economy.

Organisational change can be continuous or episodic in pace, and incremental or radical in nature. By combining these two dimensions, four types of organizational changes can be identified. While radical change is frame-bending and typically episodic, incremental change is regarded as conforming to existing practice and hence does not lead to radical change.

Li, F (forthcoming). Sustainable Competitive Advantages via Temporary Advantages: Insights from the Competition between American and Chinese Digital Platforms in China. British Journal of Management. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1467-8551.12558