California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier academic management journal published at UC Berkeley

by Yolanda Blavo, Grace Lordan, and Jasmine Virhia

Image Credit | Francois Olwage

The way in which we work has changed drastically in the past few years, and it continues to evolve. During the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, numerous employees were required to work from home, which expanded the notion of which tasks could be done remotely.1 For example, discussing business strategies with clients and colleagues or monitoring market conditions. As the pandemic restrictions have lifted, there has been an increasing trend of employees seeking the opportunity to work remotely at least some of the time.2 Concurrently, some finance and tech organizations, such as Apple, Google, Twitter, JP Morgan, and Goldman Sachs, are requiring employees to return to the office at least three days a week.3 In contrast, organizations such as Spotify, Reddit, and UBS have continued to allow employees to work completely remotely.2,4,5

“Balanced Workplace Flexibility: Avoiding the Traps” by Ellen Ernst Kossek, Rebecca J. Thompson, & Brenda A. Lautsch. (Vol. 57/4) 2015.

Overall, the ability to work autonomously can be viewed as a job amenity in the same way that people look for high-income status or pension benefits when choosing a role. It is, therefore, no surprise that some employees have chosen to leave their organization rather than sacrifice their ability to work autonomously.6 Notably, women are more likely to leave.

Another change to the workplace that has recently been featured in the news is that several organizations have chosen to make the four-day workweek permanent.7 Although the four-day workweek does provide employees with more flexibility, we argue that even more autonomy can be given to workers who do not need to be on-site to satisfy operations. That is, we agree that the four-day workweek should be trialed where possible for roles like cashier and assembly line worker, where people have to show up at work in order to be productive. However, we believe that more autonomy to choose hours can be offered to people in knowledge work roles where hours worked do not translate to performance. Moreover, the four-day workweek may result in people working fewer days but longer hours. This has implications for the type of talent an organization can attract into a role.

We argue that leaders should place a stronger emphasis on employees’ output as opposed to focusing on hours worked. The needs of employees are varied, and where people work most productively is unique to each individual. Therefore, we posit that there is no ideal singular approach that leaders should implement regarding the organization of work and time.

Our argument is supported for professional workers in finance and professional services by our latest research on behalf of Women in Banking and Finance, which involved 100 in-depth interviews with employees of all career stages in the UK.8 We called this study 100 Diverse Voices, given that the employees differed widely in terms of self-identified diversity characteristics (i.e., race/ethnicity, gender, abilities, parenting, sexual orientation, etc.). This large and diverse sample allowed us to capture a variety of perspectives. We asked our 100 diverse voices about their perceptions of what the future of work should entail allowing for a productive, inclusive workforce. Interestingly, none of the diverse voices stated that they would choose to be in the office most of the time. In fact, 95% of the participants advocated for a more autonomous mode of working. From the participants’ perspective, working remotely did not appear to decrease productivity, and some participants even noticed an improvement in their productivity working remotely. Our research illuminated that employees would benefit from greater autonomy regarding where and how they work.

Moreover, according to many of the participants, trust was paramount to facilitating this autonomy. Our findings support that leaders take a ‘remote-first’ approach, which consists of running operations without expecting employees to commute to the office regularly. Offering remote working options has implications for the inclusion of all employees. For example, the opportunities for employees with disabilities have increased.9 Additionally, we found that a ‘remote-first’ approach can be particularly beneficial for parents or people with caring responsibilities to balance their work and non-work responsibilities better.

For a ‘remote-first’ approach to be successful, our research suggests that leaders should relinquish some control and be wary of micromanaging employees because it may negatively affect productivity. Further, we found that leaders’ desire for control can be detrimental to the mental health of employees and their sense of psychological safety. Micromanagement can manifest as excessive monitoring of employees, which is motivated by a desire for control. Monitoring can include checking up on employees very frequently through constant emails, instant messaging, and meetings. Incessant work-related communications are problematic because they may distract employees from other, more meaningful tasks. Some managers may not trust employees if they cannot see them physically working, and trust issues may worsen when employees work from home.10 This is likely due to being heavily influenced by narratives of presenteeism in the workplace.

Narratives of presenteeism have plagued the workplace in that many employees are rewarded in terms of compensation based on working longer hours.11 In this way, there is often a greater emphasis on perpetuating presenteeism as opposed to supporting actual productivity. To move away from presenteeism, leaders should focus on clear and measurable outputs instead of hours worked. These outputs should be the basis for performance evaluations, promotions, and pay. This shift can have positive implications for minimizing pay gaps because those with caring responsibilities may be unable to work longer hours. Therefore, focusing on rewarding employees based on clear outputs instead of hours worked can help reduce pay gaps.11 Although it may be challenging for some leaders to trust employees to be productive, there is empirical evidence that providing employees with more autonomy can actually help to improve their performance.12

Leaders should prioritize fostering high trust-high competency work environments by providing employees with more autonomy. We propose that leaders give employees autonomy regarding where and when they work. This means providing employees with time to attend to their non-work responsibilities and also to take a break when it is necessary. Allowing employees to take a break can support employees’ mental health and work engagement.13 According to 51% of our participants, they experienced stabilized or increased productivity as a result of increased autonomy. A ‘remote-first’ approach allows leaders to create a truly flexible environment that supports autonomy and trust. Numerous studies have shown that trust is essential for remote working to be advantageous.14-15

Also, for employees to thrive with a great amount of autonomy, leaders should give employees clear objectives, and they should be empowered to be innovative and take risks without receiving backlash. If they are unsure about something, they should feel psychologically safe enough to raise this concern to their leader. Thus, a high-quality working relationship between leaders and their subordinates is essential to building mutual trust.

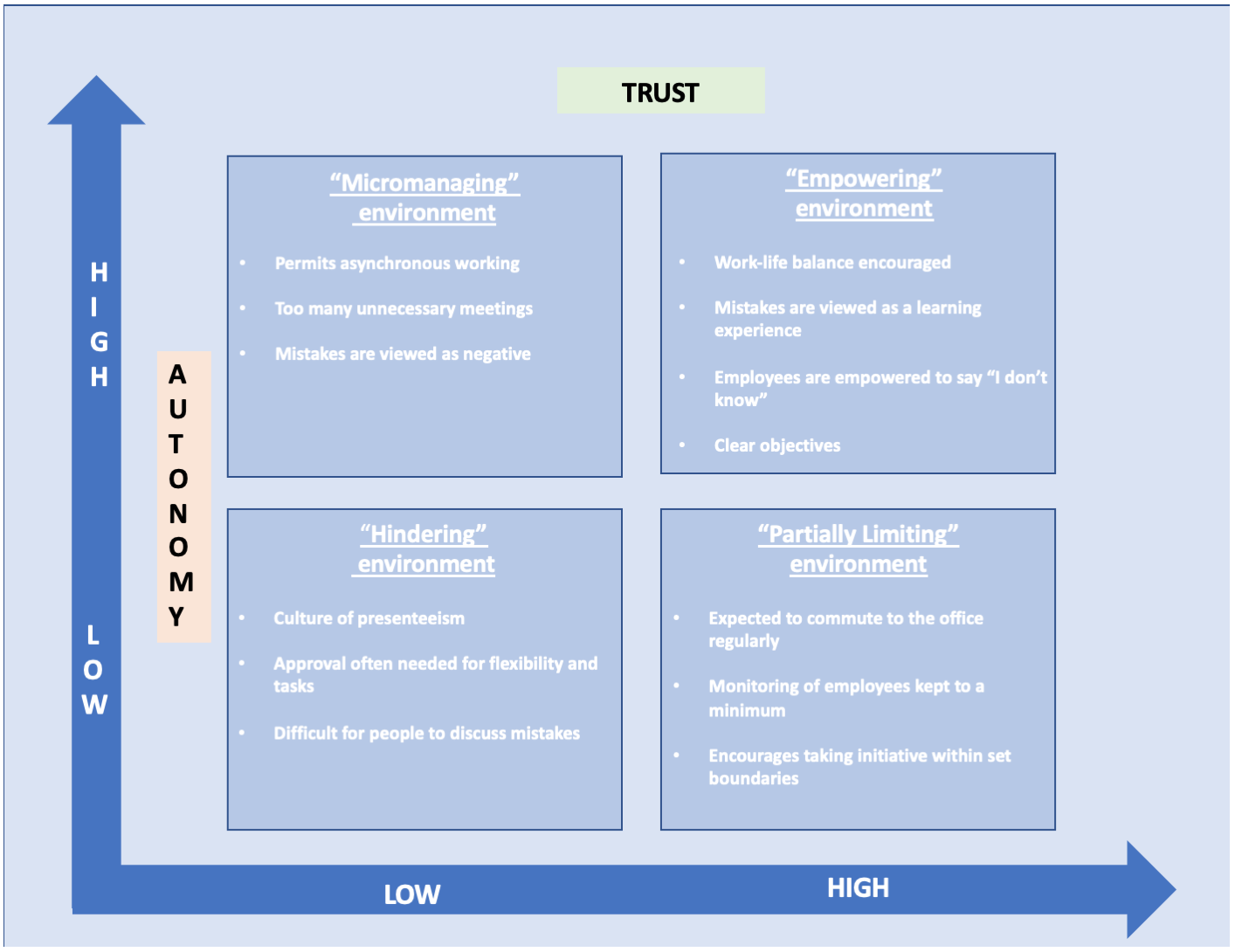

Figure 1. Autonomy-Trust Environment

To engender trust in remote work environments, leaders should make time for the socialization of employees and team building.16 Socialization is generally discussed in reference to new joiners; however, it should continue to be a priority for all employees. To support team building, leaders should make sure that team members are very clear on their roles and what is expected of them. Moreover, leaders should know their employees well and should connect them to the team’s mission.

The importance of employers fostering a sense of belonging in a hybrid or remote work environment was raised by 30% of the participants. The participants acknowledged that it could be more challenging to bond with team members when working remotely. Perceived organizational support is critical to employees’ sense of belonging. To support employees in a remote environment, leaders should be mindful of the quality of feedback they give to employees and should be there to advise and support employees if they experience challenges.17 When employees feel supported by their organization, it can strengthen their commitment to their organization and can lead to improved performance.18

Another aspect of team building could also include more voluntary, informal, and inclusive activities that allow team members to bond, such as virtual escape rooms, coffee chats, and book clubs. It is noteworthy that the ‘remote-first’ approach does not suggest that there are no times at which it is beneficial for employees to come to the office. In fact, 36% of the participants expressed that they enjoyed coming into the office for collaboration with team members and for problem-solving purposes. It could be helpful to be in the office at the same time on some agreed-upon days, but the option to work remotely should still be available for employees who may need it.

To determine whether ‘remote-first’ is suitable for an organization, leaders should experiment. For experimentation to be useful, leaders must clearly define the ideal outcome of the ‘remote first’ intervention. Leaders may opt for a ‘before-and-after’ approach consisting of implementing a ‘remote-first’ strategy and observing whether there is an upward or downward trend in employee performance over time. It may take an extended amount of time to examine the effects of the intervention on productivity. Thus, leaders could evaluate the intervention at six-month intervals.

Additionally, it could be useful for leaders to document their observations at the team, function, and firm levels to see whether there are differences in performance and work engagement. Instead of relying on their instincts, leaders should seek advice from team members to see how they can improve operations. It could be worthwhile for leaders to ask team members how they organize their work and time. If any challenges arise, they may also consider upskilling by receiving training to support remote teams better.

Leaders could also allow teams to experiment with how many days they work remotely compared to how many they work in the office and see what works best for them and their productivity. It is imperative that leaders continue to check in with employees as they make these changes to determine what the optimal approach is for a particular team. Allowing for experimentation with modes of working enables leaders to make decisions that support the productivity of a team and to deviate from presenteeism.

Key takeaway: Implementing a ‘remote-first approach’ and empowering employees with more autonomy can be advantageous for both firms and employees. However, more autonomy is unlikely to lead to favorable outcomes if leaders do not foster a high-trust environment. Therefore, leaders should get comfortable with having less control and should focus on what their employees are actually achieving.

Lund, Susan, Anu Madgavkar, James Manyika, and Sven Smit. “What’s next for Remote Work: An Analysis of 2,000 Tasks, 800 Jobs, and Nine Countries.” McKinsey & Company. McKinsey & Company, November 23, 2020. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/whats-next-for-remote-work-an-analysis-of-2000-tasks-800-jobs-and-nine-countries.

Estrada, Sheryl. “Finance Employees See the Future of Work as Hybrid, a Study Finds.” Fortune. Fortune, November 29, 2022. https://fortune.com/2022/11/29/finance-employees-future-of-work-hybrid-return-to-the-office/.

Emily Canal, Marguerite Ward. “Here’s a List of Major Companies Requiring Employees to Return to the Office.” Business Insider. Business Insider. Accessed March 27, 2023. https://www.businessinsider.com/companies-making-workers-employees-return-to-office-rto-wfh-hybrid-2023-1.

Pratt, Louron. “Reddit Introduces Remote-Working Policy.” Employee Benefits, November 9, 2020. https://employeebenefits.co.uk/reddit-introduces-remote-working-policy/.

| “Work from Anywhere: Life at Spotify.” Work From Anywhere | Life at Spotify. Accessed March 27, 2023. https://www.lifeatspotify.com/being-here/work-from-anywhere. |

“Women in the Workplace 2022.” McKinsey & Company. McKinsey & Company, October 18, 2022. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/diversity-and-inclusion/women-in-the-workplace.

“A Hundred UK Companies Sign up for Four-Day Week with No Loss of Pay.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, November 27, 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2022/nov/27/a-hundred-uk-companies-sign-up-for-four-day-week-with-no-loss-of-pay.

Virhia, Jasmine, Yolanda Blavo, and Grace Lordan. “Www.wibf.org.uk.” Accessed March 27, 2023. https://www.wibf.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/WIBF-ACT-100-Diverse-Voices.pdf.

Alexiou, Gus. “Remote Work Boosts Employees with Disabilities, Research Shows.” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, October 29, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/gusalexiou/2022/10/27/new-research-confirms-boon-of-remote-working-for-disabled-employees-in-the-us/.

Sewell, Graham, and Laurent Taskin. “Out of sight, out of mind in a new world of work? Autonomy, control, and spatiotemporal scaling in telework.” Organization studies 36, no. 11 (2015): 1507-1529.

Boustan, Leah Platt, Carola Frydman, and Robert A. Margo. “Introduction to” Human Capital in History: The American Record”.” In Human Capital in History: The American Record, pp. 1-14. University of Chicago Press, 2014.

Johannsen, Rebecca, and Paul J. Zak. “Autonomy Raises Productivity: An Experiment Measuring Neurophysiology.” Frontiers. Frontiers, April 19, 2020. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00963/full.

Kühnel, Jana, Hannes Zacher, Jessica De Bloom, and Ronald Bledow. “Take a break! Benefits of sleep and short breaks for daily work engagement.” European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 26, no. 4 (2017): 481-491.

Richardson, Julia. “Managing Flexworkers: Holding On and Letting Go.” Journal of Management Development. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, February 9, 2010. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/02621711011019279/full/html.

Bailey, Diane E., and Nancy B. Kurland. “A review of telework research: Findings, new directions, and lessons for the study of modern work.” Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior 23, no. 4 (2002): 383-400.

Blanchard, Anita L., and Joseph A. Allen. “The entitativity underlying meetings: Meetings as key in the lifecycle of effective workgroups.” Organizational Psychology Review (2022): 20413866221101341.

Liu, Yanyan, Nan Xu, Qinghong Yuan, Zhaoyan Liu, and Zehui Tian. “The Relationship between Feedback Quality, Perceived Organizational Support, and Sense of Belongingness among Conscientious Teleworkers.” Frontiers in psychology. U.S. National Library of Medicine, April 6, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9019059/.