California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier professional management journal for practitioners published at UC Berkeley Haas School of Business.

Kimberley Breevaart, Barbara Wisse, and Birgit Schyns

Image Credit | Christina @ wocintechchat.com

Psychological abuse by supervisors occurs when employees are subjected to verbal and non-verbal aggression over an extended period (Tepper, 2000). This includes behaviors such as outbursts of anger, ridiculing employees, invading their privacy, falsely blaming them, as well as manipulating, ignoring, and isolating them. International research shows a prevalence of destructive leadership of 13.6% (Schat et al., 2006). It may seem wise for an abused employee to leave as soon as possible or take other actions to end the psychological abuse. However, this is easier said than done due to various barriers that make it difficult, if not impossible, to leave.

“Perfectly Confident Leadership” by Don A. Moore. (Vol. 63/3) 2021.

“Transformational Leader or Narcissist? How Grandiose Narcissists Can Create and Destroy Organizations and Institutions” by Charles A. O’Reilly & Jennifer A. Chatman. (Vol. 62/3) 2020.

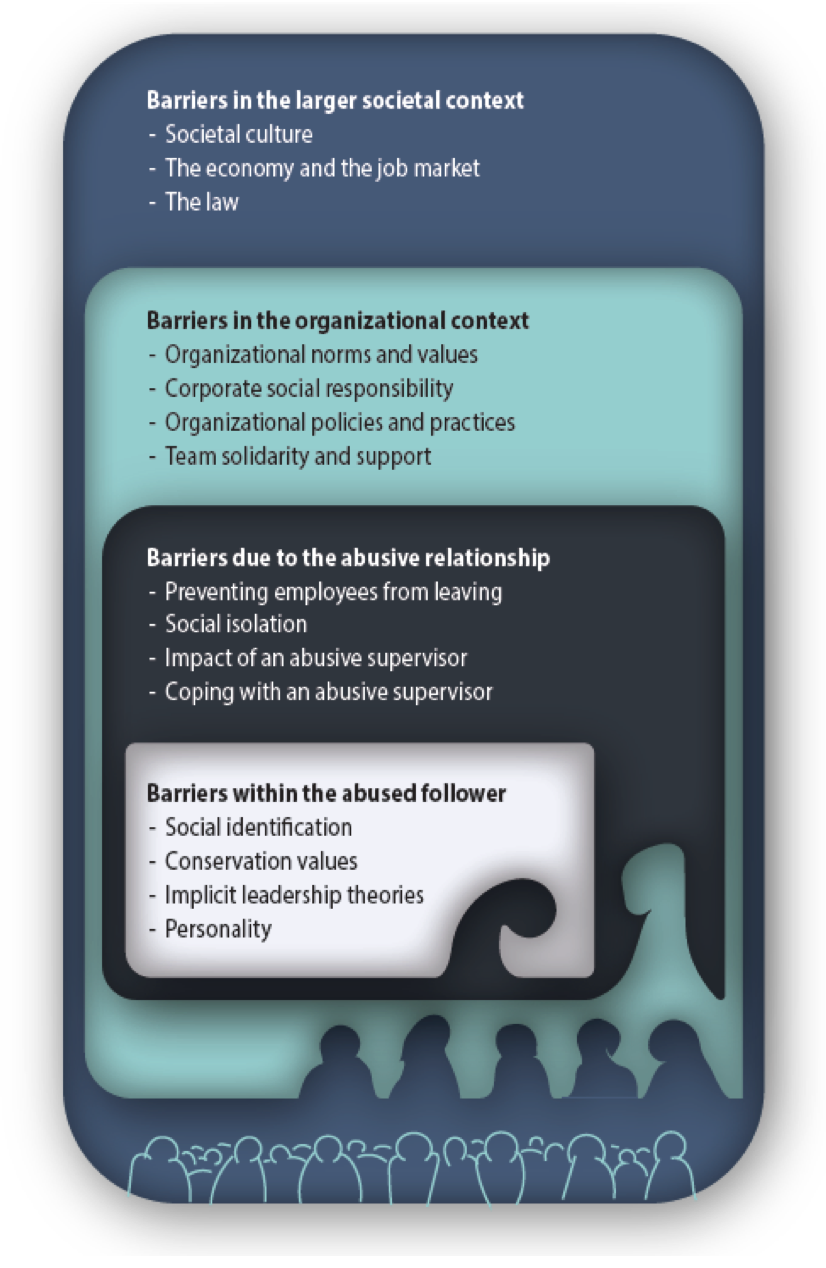

To better understand the difficulties victims face in leaving an abusive supervisor and to provide better support to victims, we developed the barrier model of destructive leadership (Breevaart, Wisse, & Schyns, 2021; see Figure 1). The model places the victim at the center, surrounded by different layers representing the increasingly broader contexts in which victims may encounter one or more barriers to leaving a destructive boss or taking actions to stop the unwanted behavior. We treat destructive leadership as a systemic problem, involving not only the perpetrator and the victim but also the organization and society at large.

Figure 1. The Barrier Model of Destructive Leadership

Layer 1: Society

There are various societal barriers that can make it difficult to confront an abusive boss, such as culture, the job market, and lack of legislation. A significant barrier is the lack of societal awareness of the problem. While we have become increasingly understanding of psychological abuse in a domestic setting and recognize the difficulties in escaping such situations, this awareness is lacking when it comes to the work context. After all, it’s just “work,” and one can simply “leave,” right? Such beliefs not only make victims doubt the severity of what they are experiencing but also contribute to the lack of attention and policy development across all layers of society to support victims. Unfortunately, in many cases, it takes a severe incident like the one at France Télécom for there to be increased understanding and attention to the issue and for things to change for the better.

The job market is also a significant barrier that may make it difficult for victims to leave their abuser. When the economy is struggling and jobs are scarce, it is not always feasible to leave. Giving up a permanent contract with the prospect of starting again on a temporary contract elsewhere can be a barrier to leaving. Many people depend on their income to support their families and pay rent, making it challenging to walk away when they are dissatisfied. Additionally, it is difficult to ask your destructive boss for a letter of reference.

Legislation is not always sufficiently supportive of victims of psychological abuse in the workplace either. While many countries now have legislation on harassment, bullying, and violence in the workplace, there are also many countries where this legislation either does not exist or is vague, such as Japan, the US, and Saudi Arabia (Lippel, 2011).

Layer 2: The Organization

The organization also plays a crucial role in determining the extent to which victims feel supported and heard. In some organizations, aggression and hostility are more accepted, particularly in bureaucratic, political, or masculine organizations, making it less likely for victims to speak up (e.g., Aryee et al., 2008). The way an organization handles destructive leadership is also relevant. In some organizations, no policies are in place regarding desired or undesired behaviors, while in others, the policies are unclear and/or not enforced. The identification of risk factors for undesirable behavior is often inadequate, leading to insufficient preventive measures being taken. This means that perpetrators are not punished. Sometimes, victims are held partially responsible for the misconduct and are forced to engage in conversations with their supervisors (based on the idea of “it takes two to tango”). This exacerbates the abuse when the supervisor retaliates and reduces the likelihood of victims speaking up or leaving in the future.

Sharing negative experiences can also serve as a barrier to leaving a toxic boss. When colleagues undergo similar experiences and find support in one another, it creates a bond that enhances cohesion and solidarity among colleagues (Pennebaker et al., 2001). Therefore, victims may hesitate to leave a toxic boss when they are not the only victim, out of fear of losing mutual support and abandoning their colleagues. Ironically, something positive can sometimes perpetuate something negative.

Layer 3: The Toxic Boss

The toxic boss sometimes prevents the termination of the relationship. Destructive leaders may derive pleasure from exerting control over their victims by isolating them (Scandura, 1998). They can make it difficult for victims by refusing to provide a reference letter or speaking negatively about them to potential new employers. By leveraging their position of power, toxic bosses can also restrict employees’ access to important information or convince them that nobody will take them seriously. Additionally, out of fear of becoming victims themselves, colleagues may exclude victims from social interactions.

There are various ways in which victims cope with psychological abuse, but these often do little to improve the situation. Victims may reach a point of exhaustion and lack the energy to change their circumstances. Some may try even harder to escape the abuse, while others may even sympathize with the toxic boss (Tepper, 2007). However, these responses only serve to further exhaust victims or blur their perception of their situation, preventing them from recognizing its abnormality.

Layer 4: The Victim

While victims are never responsible for the abuse, the individuals themselves do play a significant role in the decision to stay or leave a toxic leader. For example, individuals who place a high value on social relationships and have a forgiving nature are more likely to believe that the situation will improve and may be more inclined to forgive their boss, thus delaying their departure. Those who are cautious tend to adhere to the expectations of others, such as their boss, and strive to conform to social norms, making them less likely to leave a toxic boss.

Previous experiences with psychological abuse, such as during childhood or in prior work relationships, can also influence victims’ reactions to a toxic boss. These experiences may unconsciously lead individuals to believe that escaping psychological abuse is impossible, making them less likely to act and take control over their situation.

Because victims of abusive supervisors can face multiple barriers across different layers, a systemic approach to breaking down barriers is crucial. This means not only acting against the perpetrator but also addressing societal issues, organizational dynamics, and involving occupational health professionals, HR departments, confidants, and colleagues.

First and foremost, it is essential to take destructive leadership and its effects seriously. Destructive leadership is often downplayed because it is perceived as infrequent. However, at present, somewhere between 10 and 15% of employees are victims of a toxic boss. Moreover, the fact that something is not prevalent does not mean we should not take it seriously. Consider, for example, domestic violence. Statistics from the UK indicate that 7.5% of women and 3.8% of men become victims of domestic violence each year (Elkin, 2019). Does this mean we should not take it seriously? Of course not. Data from the World Health Organization (WHO, 2021) reveals that 1 in 3 women will be a victim of domestic violence over their lifetime. This is comparable to the prevalence of destructive leadership: eventually, many individuals will experience a toxic boss at some point in their career. Victims need our help, which means we must support them and not ignore their experiences.

Creating societal awareness of the problem is a powerful way to break down barriers. Consider the global movement such as #MeToo. This movement empowered more women to speak out against sexual violence, led to the development of laws for better protection of victims, and raised funds to support individuals in their pursuit of justice. The World Health Organization plays a crucial role in acknowledging workplace abuse and providing information for policymakers. Currently, the World Health Organization recognizes elder abuse as a hidden health issue but has yet to fully recognize abuse in the workplace. While occasional attention has been given to the problem (see Cassitto et al., 2003), hopefully, the realization that workplace abuse deserves attention will also grow within the World Health Organization.

In the field of legislation, there is still much room for improvement. Criminalizing the so-called “coercive control” – a pattern of threats, humiliation, intimidation, or other forms of abuse aimed at causing harm, punishment, or fear to the victim – is not only crucial in the workplace context but also in domestic settings. Separately criminalizing this type of violence sends an important signal that society takes it seriously and considers it significant. However, changing the law often requires collective actions from the public (e.g., protests) and/or labor unions. Professionals also need to speak out to urge Parliament to act and create positive change.

Organizations should also act against destructive leadership. However, research shows that victims of destructive leadership often cannot rely on their organization for support (Courtright et al., 2016). Organizations that do not enforce consequences for undesirable behavior experience more instances of destructive leadership (Zhang & Bednall, 2016). It is crucial to have clear guidelines on desired and undesired behaviors and the consequences of inappropriate conduct. Ideally, leaders engaged in psychological abuse should be removed from their positions of authority. Having a clear policy is a win-win situation, where leaders are less likely to engage in destructive behaviors, and victims feel supported to speak up.

The colleagues of both leaders and victims play a crucial role in breaking down barriers (Ng et al., 2022). Leaders need to speak out when they witness destructive behavior from their colleagues. Colleagues of victims also have a responsibility. Although they may find themselves in a difficult position as they are often dependent on the same leader, they can still support the victim by ensuring they have access to important resources (e.g., HR, confidants, company doctors). Ideally, the victim should not have to rely on the leader for access to these resources. Colleagues, especially those who are unsure how to address the issue and may avoid it, need to remain vigilant and ensure they do not blame the victim for the abuse and deny them help (Mulder et al., 2016).

Sometimes, company doctors and confidants tend to help by encouraging victims to discuss the situation with HR and/or leaders. However, there is a danger in this approach as victims may be subjected to further harm, such as when leaders shift blame onto the employee during a conversation with a mediator or when the destructive behavior continues after a discussion with HR. It is crucial to follow appropriate procedures and act with care. Victims need to feel heard and be treated as serious partners in seeking solutions. Referring them to a general practitioner or psychologist and discussing possible scenarios are also viable options. Company doctors can also refer victims (and/or the destructive leader) to a psychologist, with the confidant acting as an intermediary.

It is evident that we can only make a difference for victims of destructive leadership through simultaneous interventions at multiple levels. Installing good legislation alone will not be sufficient. The laws must also be enforced, and in some cases, for example, when aggression is the norm within an organization, victims need help recognizing that there is a problem in the first place. So, ask yourself: What can you do as an organization, as a colleague, as an HR professional, a trusted advisor, a company doctor, etc.?

While the focus of the barrier model is on the victims, leaders have a primary responsibility to change their behavior and put an end to the abuse. Research shows that in many cases, destructive leaders themselves experience negative consequences; they may feel guilty and less motivated, for example (e.g., Liao, Liu, Li, & Song, 2018). So why do they continue with their behavior? This is a question we aim to answer in future research by examining what exactly sustains the destructive behavior of leaders and how we can change it.

Aryee, S., Sun, L. Y., Chen, Z. X. G., & Debrah, Y. A. (2008). Abusive supervision and contextual performance: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion and the moderating role of work unit structure. Management and Organization Review, 4, 393-411.

Breevaart, K., Wisse, B., & Schyns, B. (2021). Trapped at work: The barriers model of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Perspectives.

Cassitto, M. G., Fattorini, E., Gilioli, R., & Rengo, C. (2003). Raising awareness of psychological harassment at work. In: R. Giliolo, M. A. Fingerhut, & E. Kortum-Margo, Protecting Workers’ Health Series No. 4, WHO library cataloguing-in-publication data.

Chrisafis, A. (2019). Former France Télécom bosses given jail terms over workplace bullying. Retrieved from: The Guardian

Courtright, S. H., Gardner, R. G., Smith, T. A., McCormick, B. W., & Colbert, A. E. (2016). My family made me do it: A cross-domain, self-regulatory perspective on antecedents to abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 59, 1630-1652.

Elkin, M. (2019). Domestic abuse victim characteristics, England and Wales: Year ending March 2019. Retrieved from: ons.gov.uk

Liao, Z., Liu, W., Li, X., & Song, Z. (2019). Give and take: An episodic perspective on leader member exchange. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104, 34-51.

Pennebaker, J., Zech, E., & Rimé, B. Disclosing and sharing emotion: Psychological, social and health consequences. In: M. Stroebe, W. Stroebe, R.O. Hansson, & H. Schut, Handbook of bereavement research: Consequences, coping, and care, American Psychological Association: Washington DC 2001, p. 517-539

Scandura, T. A. (1998). Dysfunctional mentoring relationships and outcomes. Journal of Management, 24, 449-467

Schat, A. C., Frone, M. R., & Kelloway, E. K. (2006). Prevalence of workplace aggression in the US workforce: Findings from a national study. In E. K. Kelloway, J. Barling, & J. J. Hurrell, Jr., Handbook of workplace violence (pp. 47–89). Sage Publications, Inc.

Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 178-190.

Tepper, B. J. (2007). Abusive supervision in work organizations: Review, synthesis, and research agenda. Journal of Management, 33, 261-289.van Dam, L. M. C., Mars, G. M. J., Knops, J. C. M., Hooftman, W. E., de Vroome, E. M. M. Ramaekers, M. M. M. K., & Janssen, B. J. M. (2020). National enquete arbeidsomstandigheden 2020. TNO, CBS Leiden, Heerlen.

World Health Organization (2021). Voilence against women. Retrieved from: who.int

Zhang, Y., & Bednall, T. C. (2016). Antecedents of abusive supervision: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Business Ethics, 139, 455-471.

Insight

Rajeshwari Krishnamurthy et al.

Insight

Rajeshwari Krishnamurthy et al.

Insight

Fariba Latifi

Insight

Fariba Latifi