California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier professional management journal for practitioners published at UC Berkeley Haas School of Business.

Image Credit | Kristian Egelund

Digital transformation has given rise to open models of innovation, distributed forms of organization, and shared business models. Brands, however, have remained confined to the traditional boundaries of their firms. Considered by some as a firm’s most valuable resource, brands attract investors and talent, provide heuristics for the quality of goods and services provided to consumers, and foster loyalty.

“The Brand Relationship Spectrum: The Key to the Brand Architecture Challenge” David A. Aaker & Erich Joachimsthaler. (Vol. 42/4) 2000.

“The Boon and Bane of Blockchain: Getting the Governance Right” by Curtis Goldsby & Marvin Hanisch. (Vol. 64/3) 2022.

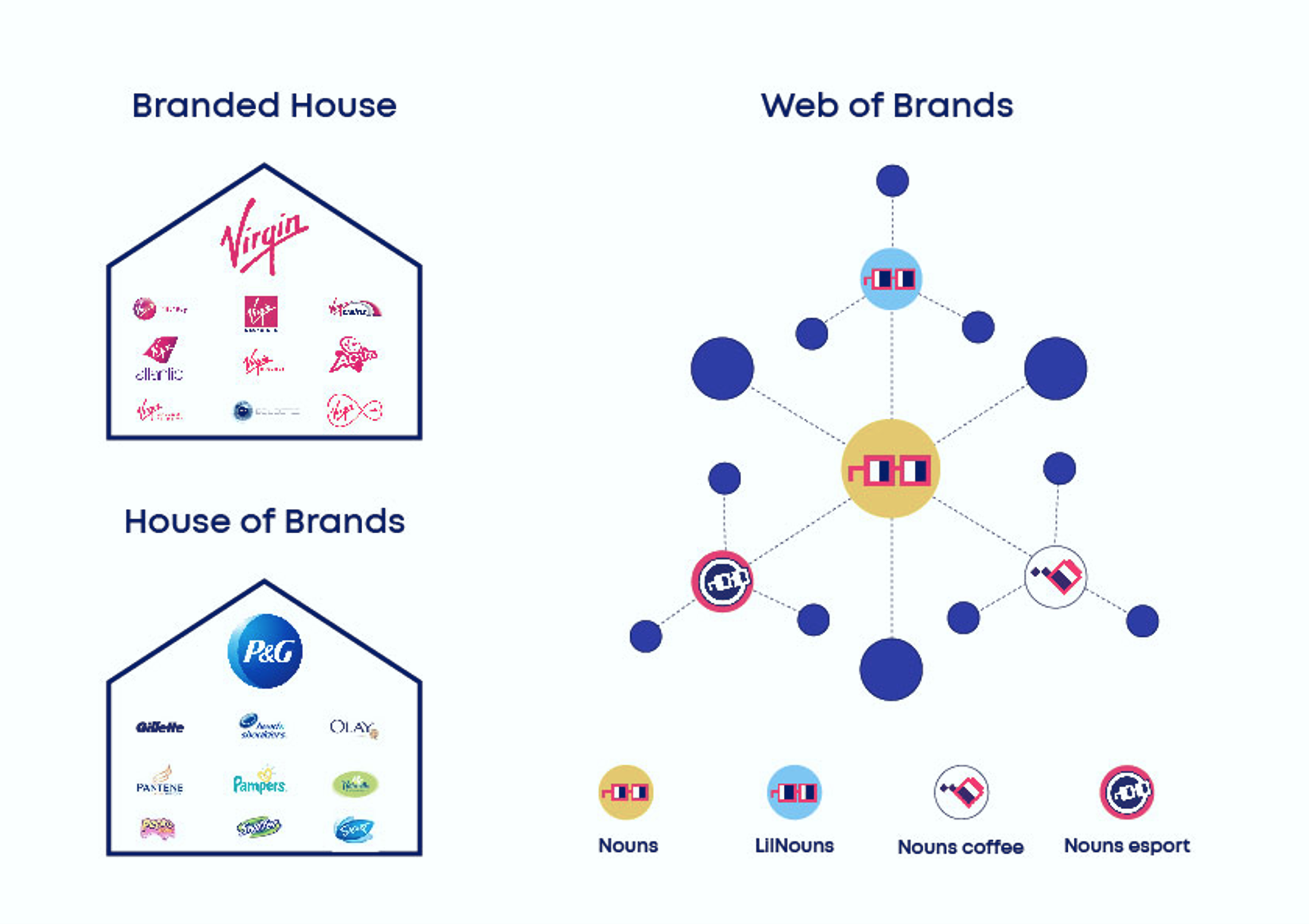

Brands are built around a name, design, color, symbol, or any artwork that serves as a cue of corporate culture, product quality, or sometimes personality. As a source of competitive advantage, firms protect these aesthetic features of their brands with trademarks and copyrights to build and maintain a brand reputation.1 This prevents third parties from using these brands in contexts other than those orchestrated by the firm or for other products and services. As they grow, firms scale their brands as ‘houses of brands’ or ‘branded houses.’1 (Figure 1a and 1b)

Figure 1. a) Branded House of Virgin, b) House of Brands of P&G, and c) Web of Brands of Nouns

‘House of brands’ architecture is organized around a core corporate brand with many subbrands. For instance, Procter & Gamble owns 65 distinguishable subbrands, such as Pampers, Gillette, and Tampax. With this model, firms can experiment with new products and markets while protecting their core brands from reputational damage. It can be difficult, however, to instill a new brand into consumers’ minds. In ‘branded house’ architecture, a core brand is directly associated with subbrands. Virgin Media, Virgin Galactic, and Virgin Mobile, for instance, all share the Virgin name. This direct association facilitates market entry by leveraging the reputation of the core brand but discourages experimentation, as any faux pas can hurt the core brand.

With both architectures, firms manage their house brands behind closed doors, taking a top-down approach to decision-making that trickles to their subbrands. Managers’ are tasked with designing an appropriate organizational structure to deploy their brand portfolios and attracting the right talent and skills to execute their decisions. In other words, the strategic management of brands is mostly performed behind closed doors within the house. We believe that emerging technologies offer new avenues to build, manage and grow brands, and we call such brands ‘open brands’.

Using blockchain technology and governed by online communities, open brands embrace open-source principles and harness the wisdom of the crowd to grow. This model turns the process of brand building upside down, akin to models of innovation that have moved from closed, top-down processes to open, bottom-up processes. First, we flesh out the main characteristics of an open brand. Second, we illustrate this model with Nouns—an experiment built on the Ethereum network, a blockchain technology. We show how Nouns provides a model for managing brands with online communities at the core. Finally, we highlight opportunities for open brands and the challenges faced in leveraging them.

The ‘open brand’ concept sounds like an oxymoron. Corporate brands are usually considered ‘closed’, that is, carefully built and protected within a firm’s boundaries. Instead of being characterized by firms, hierarchical governance, and legal protections, open brands are characterized by communities, decentralized decision-making, public-domain artwork, and the use of blockchain technology.

Whether it is organized as a branded house or a house of brands, firms traditionally own house brands. In contrast, open brands blur the barrier between firms and consumers by shifting ownership to online communities. Open brands are initially created by a small group of founders and managed by a progressively larger crowd. Members acquire affiliation with the brand—often in the form of a digital asset—and bring their knowledge and social capital, turning the exercise of brand-building into a form of collective action. As such, consumers can acquire decision rights over the common treasury and contribute to the scaling activities of the open brand.

Instead of an expanding house, open brands develop into ‘webs of brands’ (Figure 1c). Community members self-organize around a set of common assets (brand name, design, treasuries, etc.) to determine the direction of the brand.3 Protocols facilitate the coordination of the community, and any member can launch new product lines, suggest growth strategies or create subopen brands with their own communities. Each project extends the open brand in a network-like fashion by rallying a faction of the community and tapping into new audiences. Ultimately, open brands crowdsource products and strategies thereby benefit from the experimentation afforded by the house of brands model but maintain their identity as branded houses thanks to public -domain artwork and blockchain technology.

Open brands have artwork, fonts, and various distinguishable aesthetic features in the public domain. Anyone can copy, modify, and recombine them into marketable products, services or subopen brands. Effectively, public-domain artwork functions similar to open-source code or open-source hardware, providing a platform on which to experiment and innovate.4 The more relatable and remixable art is, the more likely users will be able to identify with the open brand and reuse it in various contexts. In other words, open brands use public-domain artwork with a high level of “meme-ability” potential.

While aesthetic features are available to anyone for use, open brands also have ways to build reputations and legitimacy thanks to blockchain technology. Indeed, votes cast by the community are recorded on a public blockchain, allowing any user to verify which projects have received the approval of the open-brand community. Furthermore, blockchain technology is used to track the provenance of digital assets, allowing users to distinguish official uses from counterfeited uses. As such, open brands rely on technology instead of legal instruments to protect their reputations and build a legacy.

Open brands are vested with powerful scaling and incentive mechanisms that traditional brands do not enjoy. First, open brands are more similar to memes –humorous images or videos modified and sent via the internet – than to traditional brands insofar as they actively invite experimentation with their aesthetic features instead of preventing it. As such, any iteration of this artwork increases awareness of the original one in the same fashion that academic citations give credit to and build upon foundational papers.5,6 Second, the community members of open brands are both intrinsically and extrinsically motivated to scale. Indeed, membership not only facilitates fun and social belonging but also allows owners and community members to benefit financially from the success of the open brand. This diminishes the classical agency costs present in principal-agent situations with house of brands or branded house models. Finally, and relatedly, the radical transparency and inclusiveness of open brands brings legitimacy to the direction of the brand and helps form a sense of common identity within the community that fuels participation, loyalty, and authenticity.7

Nouns is an open brand with serious ambitions. The defining aesthetics of the brand are cartoon characters with square-framed glasses—Nouns—that can be used as avatars in online communication channels and social media (see Figure 2). The project was launched by a team of 10 contributors, some of whom are anonymous, such as 4156, and some of whom are known individuals, such as Dominik Hofmann, a cofounder of Vine.

Figure 2. Eight different Nouns randomly generated and auctioned by an algorithm

Nouns have appeared on a Budweiser Super Bowl advertisement and in the contexts of e-sport teams and products such as streetwear, skateboards, and comics. The success of Nouns lies in their highly memeable aesthetics in the public domain, their use of blockchain protocols, and their decentralized governance mechanisms.

Each Noun is the product of a generative algorithm that creates ‘one Noun every day, forever’. The components (glasses, background, body, accessories, and head) of Nouns were designed by a group of artists including Gremplin and the collective eBoy Arts, among others. The algorithms can build millions of unique Noun combinations, and the experiment can run for hundreds of thousands of years. Importantly, the art used to design Nouns is under CC0 licensing, that is, ‘no rights reserved’ licensing, meaning that anyone can copy, modify, and commercially reuse the art. As such, the Noun glasses quickly became the defining aesthetic of the open brand and have been reused in a great variety of contexts (Figure 3). Hundreds of derivative (subbrand) projects have adopted a “Nounish” look by using square-framed glasses and transposing this concept to other physical and digital goods.8 The combination of CC0 licensing and remixable and distinguishable artwork is the first set of ingredients that explains the success of Nouns.

Figure 3. Noun glasses making their appearance in the Budweiser Superbowl advertisement

Anyone can right-click and save a picture of a Noun, but instead, people pay 5 figures to acquire an original one, certified with blockchain technology, through an auction mechanism. All the proceeds go to a treasury managed by a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO)—the Nouns DAO. People are willing to pay for original Nouns because the digital asset grants a vote in the management of the treasury. Additionally, if their open brands succeed, Noun owners expect the value of their Nouns to increase.

The Nouns DAO is the governing body that can change the art-generating protocol and manage the treasury resulting from sales of Nouns. At its core, the collective is an online community made of anonymous members organized as a DAO. DAOs resemble institutions in terms of collective action because they manage a common pool of resources;9 however, they differ in their use of decentralized and trustless governance mechanisms. Specifically, these mechanisms rely on smart contracts—automated algorithms executed on the Ethereum blockchain—to manage memberships and voting.

In its existence of slightly over a year, the Nouns DAO has amassed a treasury worth more than 24k ETH (approximately 40 million USD) and a core community of more than 290 members. More than 150 proposals have been made, and 117 have been executed, including donations to charities, the development of product lines such as clothing or comics using the Noun brand, and the financing of NounDAO operations. Additionally, retroactive funding has been granted for projects and individuals who have built successful initiatives for the growth of the ecosystem. For instance, 1000 ETH (approximately 1.2 million USD) has been allocated to NounsBuilder, a solution allowing anyone to replicate the Nouns model (art generation, auction, governance), thereby inviting anyone to experiment with open brands.

Nouns’ year-long experiment offers some valuable knowledge regarding open brands. First, the artwork started as profile pictures with which individuals or companies could build online identities. However, the square-framed glasses quickly proved to be a versatile resource that could be deployed in contexts as varied as software development, gaming, merchandising, or beverages. Relatable and remixable artwork in the public domain attracts large communities and invites reuse. Second, Nouns leverages digital assets on a blockchain to incorporate incentives for community participants. Members not only join the DAO for experimentation and fun but can also be financially rewarded for participation in the growth of the brands. Finally, 4156, a co-founder of Nouns, highlighted the absence of contracts signed between the Nouns Foundation and Bud Light10 in their collaboration. In some cases, blockchains could substitute for formal modes of governance such as employment or partnership agreements. Open brands can also be a tool to build legitimacy and reputation.

Open brands are here to stay, and traditional firms have two avenues to experiment with them: plug or play. The plug strategy consists of becoming a member of an open-brand community. This approach allows a firm to connect with – or to plug into - an existing audience and leverage its dedication to guerrilla marketing. It is the strategy embraced by Budweiser in its promotion of Bud Light Next – its first zero-carbohydrate beer promoted in collaboration with the NounDAO. By doing this, Budweiser displayed support for the Ethereum community and became an active member of the NounDAO, participating in 75 different proposals. The play strategy involves the creation of an open brand and experimentation with a firm’s existing audience. Firms subsidize the ingredients to bootstrap the open brand (aesthetics, governance rules, discussion platform, treasury) in the same fashion that they would provide toolkits to foster user innovation.11 They then play the role of community managers - conveying information and providing support - and let members play with their open-brand resources.

Open brands not only carry powerful promises but also come with a set of trade-offs. First, permissive licenses accompanying the artwork of open brands facilitate fast, meme-like diffusion but bring challenges in the management of brand reputation and identity. Because this artwork can be remixed by anyone, audiences may find it challenging to delineate a single culture and set of values embodied by an open brand. This leads to openness vis-à-vis the interpretation of the open brand and associated subbrands, which can prove to be a double-edged sword.12 Fortunately, the use of blockchain technology as a transparent record allows us to trace back original artwork, but it could be a barrier for less technically inclined individuals. As such, brand recognition is no longer solely guaranteed by protected aesthetics features but instead protected through the use of immutable digital records.

Second, open brands are managed by online communities known for their fluidity in membership. These allow DAOs to leverage both the knowledge and social capital of members13 for the construction and growth of brands; however, sustaining continuous and strong member engagement can be challenging. Nevertheless, the use of digital assets as membership tickets to join DAOs provides powerful intrinsic and extrinsic motivation bridges to sustain participation in the community. Furthermore, the permissionless nature of online communities potentially brings a wide variety of ideas at the expense of coordinating costs and reduced speed.14 Blockchain technology such as Ethereum render these coordinating costs tangible via the use of ‘gas fees’—up to a few hundred dollars per transaction—but scaling solutions offer promising avenues to reduce them.

Third, it remains unclear how transparent discussions on the positioning and direction of open brands—accessible by anyone—affects their competitive positioning. For instance, in the context of open innovation, it has been shown that openness benefits organizations at an early stage of development but that these organizations typically revert to more closed forms as they mature.15 In the case of open brands, it could very well be that the secret to their success is not to be found in the content of their strategies but in the competencies of the people joining the management of the commons.16

I would like to thank Prof. Scott Duke Kominers (Harvard Business School) and Prof. Patricia Wolf (University of Southern Denmark) for their helpful guidance during the writing of this article. Also, I would like to thank Andrea Lenzner and Dr. Julian Müller for their careful review and comments to improve earlier versions of this manuscript. All remaining errors are mine.

This project did not receive any funding.

The author owns Ethereum cryptocurrency.

J. Barney, “Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage,” Journal of Management 17, no. 1 (March 1991): 99-120.

D.A. Aaker and E. Joachimsthaler, “The Brand Relationship Spectrum: The Key to the Brand Architecture Challenge” California Management Review 42, no. 4 (July 2000): 8-23.

Ø.D. Fjeldstad, C.C. Snow, R.E. Miles, and C. Lettl, “The Architecture of Collaboration,” Strategic Management Journal 33, no. 6 (June 2012): 734-750.

E. Von Hippel, “User Toolkits for Innovation,” Journal of Product Innovation Management 18, no. 4 (July 2001): 247-257.

https://a16zcrypto.com/cc0-nft-creative-commons-zero-license-rights/

https://decrypt.co/106761/why-ethereum-nft-creators-are-giving-away-commercial-rights-to-everyone

J. Hautz, D. Seidl, and R. Whittington, “Open Strategy: Dimensions, Dilemmas, Dynamics,” Long Range Planning 50, no. 3 (June 2017): 298-309.

https://nouns.center/projects

E. Ostrom, “Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action,” (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

https://decrypt.co/90860/bud-light-nouns-ethereum-nft-superbowl-ad

E. Von Hippel and R. Katz, “Shifting Innovation to Users via Toolkits,” Management Science 48, no. 7 (July 2002): 821-833.

T. Meyvis and C. Janiszewski, “When are Broader Brands Stronger Brands? An Accessibility Perspective on the Success of Brand Extensions,” Journal of Consumer Research 31, no. 2 (September 2004): 346-357; S.J. Milberg, C.W. Park, and M.S. McCarthy, “Managing Negative Feedback Effects Associated with Brand Extensions: The Impact of Alternative Branding Strategies,” Journal of Consumer Psychology 6, no. 2 (January 1997): 119-140.

H. Safadi, S.L. Johnson, and S. Faraj, “Who Contributes Knowledge? Core-Periphery Tension in Online Innovation Communities,” Organization Science 32, no. 3 (May 2020): 752-775.

D.P. Ashmos, D. Duchon, R.R. McDaniel, and J.W. Huonker, “What a Mess! Participation as a Simple Managerial Rule to ‘Complexify’ Organizations,” Journal of Management Studies 39, no. 2 (March 2002): 189-206.

M.M. Appleyard and H.W. Chesbrough, “The Dynamics of Open Strategy: From Adoption to Reversion,” Long Range Planning 50, no. 3 (June 2017): 310-321.

N.J. Foss, P.G. Klein, L.B. Lien, T. Zellweger, and T. Zenger, “Ownership Competence,” Strategic Management Journal 42, no. 2 (February 2021): 302-328.

Spotlight

Sayan Chatterjee

Spotlight

Sayan Chatterjee

Spotlight

Mohammad Rajib Uddin et al.

Spotlight

Mohammad Rajib Uddin et al.