California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier professional management journal for practitioners published at UC Berkeley Haas School of Business.

by Mark Esposito, Terence Tse, and Josh Entsminger

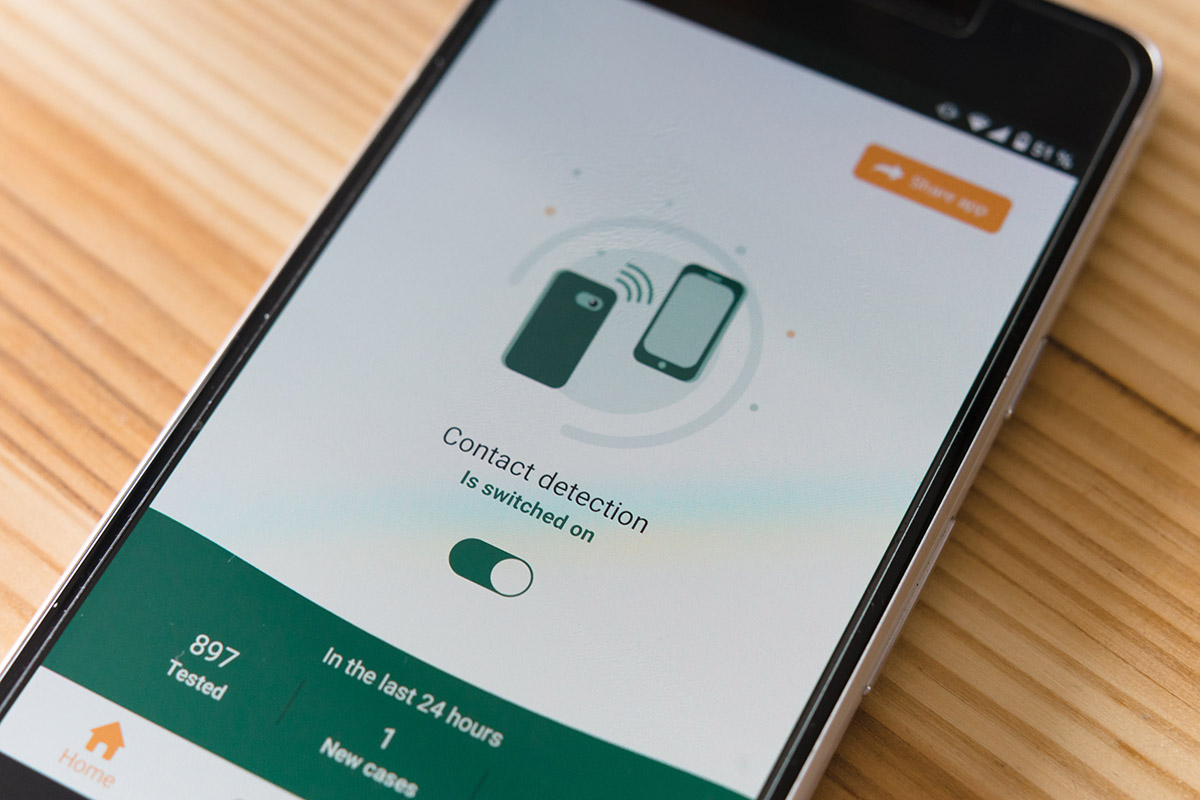

COVID-19 response has had two frontlines – one intractably physical in the handling and assistance of those infected and those uninfected, and the other in the digital sphere, centered around the way the response is managed and accentuated. The variety of digital frontline responses – from novel contact-tracing and informative chat-bots to global data cooperatives and online research paper aggregation – has helped to confirm what should be cliché: privacy is divisive, and its violation can equally become pervasive.

Fundamentally, privacy remains an argument about who should know what and why – but its scope is not exhausted by broad conversations by ethics. Privacy needs to extend to a structural question, on the kinds of digital infrastructure which empower an informed choice about what firms should know about you, through your data and analysis on that data. This structural question of privacy extends beyond the reactive approaches to pandemic management to the broader commercial structure of national digital economies and the visions of modern digital policymaking – both increasingly defined by the promise of everything-as-a-platform. As economies look towards pandemic recovery and potential re-lock down requirements, using the very digital technology at the edge of privacy and broader surveillance capacities to do so, we need to beware how new economic and competitiveness agendas make use of this expanding normalization of digital authority and what public values these agendas really serve.

Competitiveness approaches and models still defines the landscape of economic policymaking discourse, shaping how economic advantages is believed to increase standards of living across the world. But a change in the discourse is needed, as these arguments on competitiveness point not only to question of how strategy shapes living standards but how economic strategy shapes the national values are supported by businesses and those which are the first on the chopping block. The point can be put directly; the stakes of competitiveness are means the ability to resist another country using its economic power to shape domestic standards and the willingness to uphold and defense its standards – in such a data driven age, whatever shapes the privacy standards can shape the future of global commercial power. The extreme risk of COVID-19, as well as the shared nature of that risk, has driven a change in the conversation on the responsibility of different approaches to privacy when public health is at stake – but to frame the conversation as privacy or health is already a public failure.

On the surface, less privacy means more opportunities for value creation through granular, personal data sets leveraged to build algorithmic advantages. Yet the question of data is not global per se; It’s national, local, jurisdictional in the conditions of value extraction to say the least. Competing perspectives on privacy yield fundamental differences in domestic industrial activity and feasible public health planning strategies – in the day to day choices of firms as well as the baseline for national digital and economic planning. For these choices serve to shape more than the public debate – but create the legacy infrastructure and common practice by which commercial power is understood and exercised, by which governments understand assumed trade-offs between privacy and efficacy. Beliefs which, in turn, come to reflect a broader concern over the role of privacy in national strategy and economic capacity.

But such economic advantage may leave industries, as well as the wider domestic public, more susceptible to influence across a variety of levels. The strategic position of manipulation social networks is well established, but the question likewise extends to the way’s firms negotiate with one another, as well as the question not whether or not the commitment to privacy can become disadvantageous in such markets. This tension has been further pushed to the forefront with a new wave of competitiveness issues, demonstrated by the actions of American companies abroad – emerging when the actions of American institutions, like Apple, Google, Netflix, are in tension with US beliefs about rights and privacy, succumbing to commercial pressure from the potential of losing foreign market access.

Privacy is not only a choice on commercial power; rather, national choices on privacy infrastructure shape the means by which competitiveness strategies and foreign firms seek to influence one another through the data gained from respective jurisdictions. How states define their relationship to privacy stakes a claim on the nature and future of the global economic order itself in how firms and countries work with national and local data, in how value is owned and distributed, in how rights are preserved or violated. Whatever shapes the digital liberty of individuals, whether a coherent global vision or conflicting national visions, will shape the commercial pursuits underlining the structure of the new rising global economic order.

For the last generation the fight was whether the personal was indeed political - now, we need to have a more serious conversation about how the personal inexorably shapes a global order, albeit involuntarily to many. As of now indeed every day’s personal economic choices express pressure over the nature of the international order in how states choose to govern (or fail in governing) the power of data-driven practices which are responsible to frame and manipulate economic behavior and determine the rise and fall of markets and governments.

The next era of globalization needs to be understood through competing ideologies of privacy, ideologies which serve as the basis for new visions of economics and autocracy.

What is perhaps most worrying is that the best view of the divide between such ideologies may be less about markets versus the state than both in relation to the sovereignty of individuals and the increasing dystopia that the current unregulated practices over privacy tend to impose upon us.

Regardless, the reality of such a world needs to be felt and understood at the level of each individual to better establish a global public discourse on the directedness of globalization and the innovations which drive it. In a world populated by firms and governments pursuing expansive data-intensive projects, we each must take responsibility for understanding how firms and governments may compete or collaborate over the power to shape and mediate our choices. The stakes are nothing less than this: do I, as a citizen, have the right to freedom of interference and manipulation in how I make my choices? For the means by which governments and firms shape, and sell the means for shaping, those choices are growing in sophistication.