California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier academic management journal published at UC Berkeley

by Christiane Prange and Joseph A. LiPuma

The global coronavirus pandemic, like the banking crisis, or 9/11 terrorist attack, affects nearly all companies, some more so than others. Many of those most acutely impacted are those that are most internationalized, dependent on suppliers, partners, and customers in foreign markets. We argue that the success with which most players adapt to a crisis depends on how they are able to acquire knowledge beyond their core focus, and change between exploration and exploitation modes of renewing their business models.

Consider a multinational enterprise (MNE) with a well-established international supply chain, encompassing its own foreign subsidiaries and partners worldwide—an auto manufacturer, for example. Now look at a young international venture, using the power of technology to rapidly enter foreign markets with a virtual offer—maybe an e-health services provider offering remote diagnostics. Each has complex capabilities: the MNE’s capabilities are based on exploiting its size, network, and processes to drive efficiencies to deliver profits; the international new venture’s (INV) build on rapidly trying new approaches in new markets, pivoting as the industry and market evolves. One exploits, one explores, utilizing various aspects of knowledge to grow its business.

Exploitation implies maintaining a steady revenue stream from existing activities without changing fundamental assumptions in positioning. It entails adjusting procedures and activities if necessary, but returning to what worked in the past, consistent with the company’s physical and intellectual assets. The underlying assumption is that the post-crisis “new normal” should be close to the pre-crisis “old normal” as an idealized state. For instance, most global education providers were caught flat-footed by the crisis. Most of them hope to continue exploiting their business models based on high tuition and big lecture halls. However, reality shows that they are facing severe constraints in adjusting communication channels, because students—and their parents—consider online teaching as less valuable and thus, less tuition-worthy. Consequently, every university and college has to think about the future of learning and teaching, how it needs to adapt itself, even rethink its core mission, and where it delivers its value.

Exploration builds on very different assumptions. Companies learn about unfamiliar environments, discover distant consumer segments or play around with business models that may disrupt their current business. Exploration relates to experimentation with new alternatives, having returns that are uncertain, distant, and sometimes negative, and even challenging the company’s raison d’être. Typically, young companies focus on exploration because their business model is evolving and they do not suffer from constraints that may hinder experimentation. Such companies are adept at pivoting from their business model when they see better alternatives. For instance, as demand for escalator disinfectants surged during the COVID-19 crisis, a German startup that sold drinking water sterilized by ultraviolet radiation now designs a UV light box that can be built into escalators to disinfect handrails.

For the young venture focused on disinfectants, the quick adaptation of the business model promised high returns during the crisis and most likely helped it to pass the critical financial threshold for survival. In contrast, the education industry’s inertia and intention to return to normal precludes exciting trajectories in the search for new revenue streams.

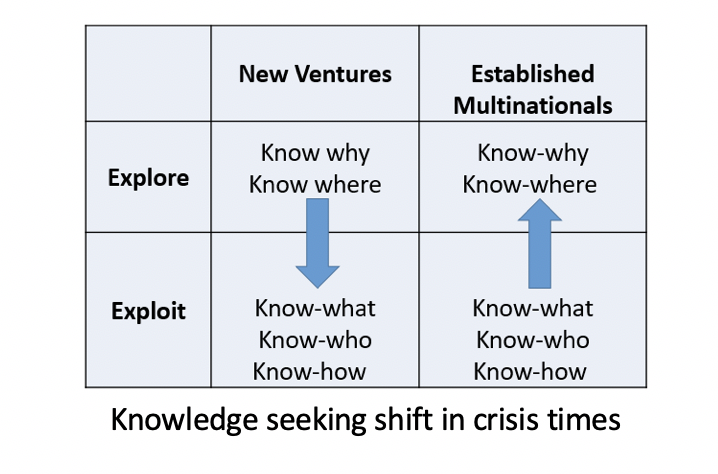

There are likely to be differences as to how and why large multinational companies deal with exploration and exploitation in the presence of external shocks as compared to smaller, younger ventures. A set of dimensions for crisis adaptation (see table) provides a means to examine the differences between MNEs and INVs.

| Multinational Enterprises | Crisis Adaptation Dimension | International New Ventures |

|---|---|---|

| Exploitation | Approach to change | Exploration |

| Gradual Change | Rate of change | Rapid pivots |

| Liability of Senescence | Key liabiility to change | Liability of newness |

| Business Model Transformation | Locus of transformation | Industry transformation |

| New Normal | Relation to normality | No normal |

| Know-what, know-who, know-how | Competitive knowledge base | Know-why, know-where |

As noted above, MNEs use exploitation as the primary means for change, in that they exploit their current resource base to extend their current business models. International new ventures, on the other hand, use exploration to seek new markets, adapting their products and business models in an attempt to capture opportunities. As such, the rate of change in MNEs is slow and incremental, whereas in INVs, rapid pivots lead to transformational changes. Large MNEs often suffer from liabilities of senescence, based on a stock of knowledge that leads them to doing more of the same rather than exploring new opportunities. In contrast, small, young ventures may suffer from liabilities of newness where they cannot rely on any pre-given sources of income, and thus must keep searching for new customers and a business model that satisfies prospective customer needs.

In the midst of crisis, these large companies seek to establish a new normal, close to the old normal and its use of company resources. INVs, however have no normal, which allows them flexibility and does not constrain them to existing resources that are often based on intangible knowledge and founders’ networks. Finally, the knowledge utilized for successful performance by MNEs is often explicit knowledge developed over time from experience, networks of contacts grown from R&D and marketing activities, and procedural knowledge related to manufacturing and service. Young internationalized companies utilize the congenital knowledge of the founders tied to their venture’s purpose, and knowledge of where that purpose may best serve market needs.

Internationalization, whether done by large MNEs or smaller, younger new ventures, depends on knowledge. The former incrementally expand to more geographically and psychically distant countries in a stepwise fashion, learning as they go, internalizing and institutionalizing that knowledge to drive them forward. The latter, INVs, quickly enter various countries, often in an opportunistic fashion, internalizing disparate market and contextual knowledge quickly due to their learning advantage of newness. Broadly, the knowledge necessary for internationalization includes knowing:

In order to understand how MNEs and INVs differ in their response to crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, let’s first explore how they utilize knowledge with exploration and exploitation under a “normal” situation.

Over time, MNEs build structures that prevent them from exploration. Age is known to negatively affect further growth by seizing opportunities that require unlearning past routines due to established cognitive, political, and relational constraints. What MNE managers know and whom they know provides the basis for their know-how, the routines that led to their prior success. These regimes create inertia and decrease alignment between the company and the crisis environment. The “Icarus paradox” MNEs face causes their success to seed their demise. A major crisis forces them to move to exploration, challenging their knowledge base and forcing them to explore their business rationale (why they exist) and where (e.g., country, industry, market) they might turn to be competitive. For example, the airline industry is deeply affected by the crisis and has come virtually to a halt (about 2% flight occurrence since March 2020). As it is doubtful whether the industry will ever return to previous passenger numbers and routes, successfully adapting airlines are considering point-to-point transportation (using know-where) to identify high-potential routes. The business model that had already been adopted by low-cost competitors, and which they had so vehemently rejected, now seems to be a valid exploratory move as it offers dramatic advantages in landing fees and other associated costs and offers better choices for customers internationally (know why).

Smaller, younger international ventures’ routines are less embedded; they can more dynamically adapt to changing environments. In short, they are much better at exploration, but sometimes lack the stability that is required for their operations; they may grow quickly, but perhaps lack consolidation in terms of leadership qualities, communication structures, or product improvement (the know-how that comes from several years of practice). Their flexibility in international business, admirable in a more stable context, can cause them to be whipsawed in a fast changing crisis situation. To grow and mature, these INVs must complement exploration with exploitation to develop routines and relationships to allow scale to actualize opportunities, building what they know, their networks, and know-how.

How do, or how should, different companies behave in a crisis like COVID-19, or others? Are either exploitative or explorative moves better to cope? Or should companies dynamically balance exploration and exploitation? While the “right” answer is industry dependent, we can provide some broad perspectives. As mentioned, large, mature companies seek a return to normal – but many of them cannot. Companies in the automotive industry, for instance, are severely affected by the crisis, as supply chains forced car production to grind to a halt—and car demand and use has declined precipitously. While automotive managers certainly pine for a fast recovery (exploitation), the pandemic will continue to shake up the whole industry—incumbents, suppliers, and customers—and their respective revenue models. Governmental subsidies were required to support sales of traditional combustion engines whereas alternative hybrid models continue to play a shadowy existence. Both the necessary infrastructure for hybrid cars and the willingness to put their development center-stage is lagging behind. Social distancing and work from home has limited automobile job commuting, the choice of 86% of American commuters. The reluctance (to explore) may soon endanger a whole industry for which “new normal” is as deadly as Icarus’ flying too high to the sun. A paradigm shift is required that builds on knowledge that is characteristically different than was used before. Past commuting statistics, relationships with auto service providers, and how to sell and service cars may be irrelevant in the future state if no one drives to offices or buys cars. In fact, realizing that the pandemic may accelerate disruption in the automotive industry is a first step towards radically implementing new mobility concepts, such as autonomous driving, the use of digital services, and electrification.

The situation is different for small enterprises that have imbibed exploration from their birth, and especially INVs that internationalized early in their lives. For example, Physee, a small, young Dutch company that produces solar-powered windows, was able to scale-up quickly by working with European developers experienced with the requirements of sustainable and carbon-independent homes. Physee utilized its know-who and built on its know-why and know-where by extending its know-what and know-how. With the pandemic affecting all households, the company is becoming increasingly more dependent on extending its network to enlarge its scope from private to business customers and to integrate solar technologies into other proven products and services to enhance revenue streams. These may include solar-powered lasers that are unique from other types in that they do not require any artificial energy source and thus, may be more applicable in countries, or to customers seriously affected by the crisis.

Crises are disruptive to companies, industries, and economies. But in these times, successful companies see these times of economic destruction as opportunities for creative destruction of old ways of doing business. New combinations of knowledge, for both large established MNEs and small, young INVs provide both incumbents and entrants means for success.

For a startup, exploration is survival; for the MNC exploitation is survival. The main message here is that MNEs should shift from exploitation to exploration in times of crisis and INVs should do the converse. This requires that MNE leaders challenge and move beyond the bounds of their knowledge and structure to explore other possibilities. INV leaders have to drive stakes down to land on emerging opportunities that will allow them to scale, developing market knowledge and networks in viable countries and establishing knowledge and processes to foster growth.