California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier professional management journal for practitioners published at UC Berkeley Haas School of Business.

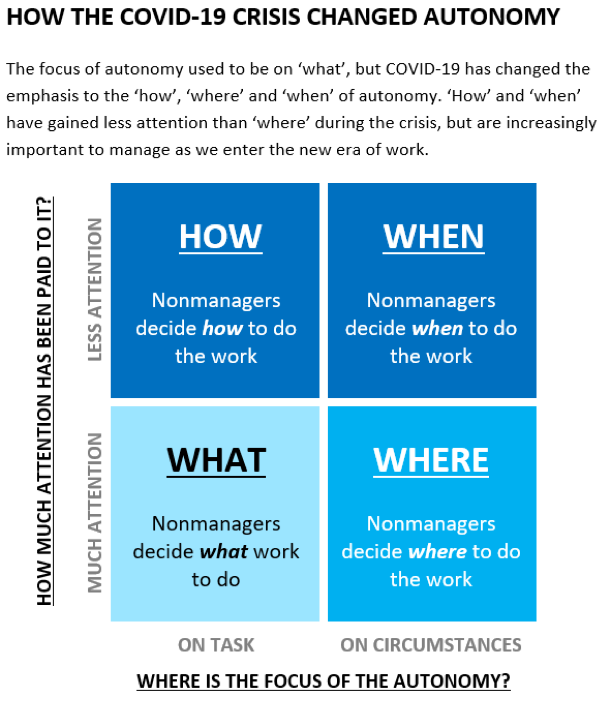

The COVID-19 pandemic is changing the modern workplace as we know it at an unprecedented amplitude and pace – and employee autonomy (i.e., an employee’s capacity to make choices on their own) is particularly illustrative of how work is changing in response to the pandemic. Specifically, we observe that the traditional emphasis on what work autonomous employees do (the content) has been complemented by where employees work (the location – e.g., from home, from a summer cottage, from a sailing boat), but even more interestingly employee autonomy now also extends into how (the process) and when (the time) employees contribute to their organizations. In theoretical terms, employees are given more ‘work method autonomy’ (how) and ‘work time autonomy’ (when) on top of their ‘content autonomy’ (what) and ‘location autonomy’ (where) in the new normal. Hence, managers need to understand this shift and prepare for how best to use it during and after the crisis (see ‘How the COVID-19 crisis changed autonomy’).

Beyond the traditional what autonomy, most employees and managers have already gained experience in terms of deciding for themselves where to work due to the sudden shift to remote workplaces and virtual collaboration. However, less attention has been paid to employees deciding on their own how and when to work. Here, we want to guide managers into this new era of work by (1) demonstrating how employees have gained autonomy during the COVID-19 crisis, particularly in how and when work is done, and (2) providing specific recommendations for how managers can best take advantage of the shift to more autonomy in how and when both now and going forward. Our work is based on our ongoing research on how companies adapt to COVID-19 and the role of employee autonomy during and after the crisis (see ‘About the research’).

The COVID-19 crisis has allowed employees to be more autonomous, as the pandemic has forced employers to distribute decision rights to a remote workforce. The increased level of autonomy is not only demonstrated by companies such as Google, Facebook and Twitter allowing employees the choice of where to work in the coming years on top of their world-famous autonomy for what to work with (as seen with Google’s 20% rule or Twitter’s hack week allowing employees to work on the pet projects of their choosing) – it is also evident in employees gaining a say in how and when to work.

For instance, Google has allocated each employee an allowance of 1,000 USD for equipment for home office—and employees are free to experiment on how to spend the money. They can also make the work experience more fun, with examples counting fitness with gfit instructors, cooking lessons by Google chefs and Kids@Home Storytime (all related to the how of autonomy). In rethinking how they could help staff with families, Facebook has announced that it would provide up to four weeks paid leave while schools are closed and encourages managers to offer flexible work hours and additional time off (related to the when of autonomy).

This trend is not solely restricted to Silicon Valley creativity: Around the globe, managers have found themselves in a new and uncertain situation without any blueprint to guide them. As a consequence, they have been forced to trust their employees in making work-related decisions on their own.

Around the globe, managers have found themselves in a new and uncertain situation without any blueprint to guide them. As a consequence, they have been forced to trust their employees in making work-related decisions on their own.

Therefore, the typical day at the office, or rather a day at work somewhere, may also look very different once the crisis is over: a research report of 8,000 employees, managers and C-suite executives found that autonomy in work schedules tripled during the pandemic and 3 in 4 of the respondents not only want to retain flexibility over working hours once the pandemic is over, they similarly demand more flexibility in how and where they can work. The report similarly found that employees have used the lockdown to build up new skills for addressing work tasks in a new manner. Simply put, the future of work is flexible and 9-to-5 might be ending, as employees demand that results, not hours, get tracked in measuring productivity – and that employees maintain the license to experiment with new ways to solve tasks. Below we elaborate further on these new dimensions of autonomy emerging from the crisis.

Employees decide how to work: Work method autonomy allows employees to decide on their own how they want to conduct their work. During the pandemic, many employees have been granted freedom in how to best approach tasks, and many changes in work design and processes are being driven by newly autonomous employees. For instance, freedom to learn and apply new digital tools for driving projects has resulted in up to 54% of the workforce stating that their digital skills have improved during the crisis with resultant increases in both productivity and quality levels of the work.

Consider the impressive rate at which universities around the world almost overnight transitioned to online teaching. At our own university, Copenhagen Business School, over 90 teaching videos had already been produced and uploaded within a day after the national lockdown. Such a rapid transition could only be possible by allowing teachers and administrative employees decision authority of how to transform classes to a digital context. As a result, many new and creative changes to work design/processes have been introduced. Studios have been built for online teaching, online forums have been developed for faculty to share best practices with each other, and the use of digital tools to test, engage and facilitate learning has been introduced, most often at the discretion of the teacher of the class. Teachers who have never taught an online class prior to the crisis are now Zoom-experts, and have been able to by-pass administrative bureaucracy in (re)developing their classes. Coordination has taken place through email, phone, or videoconferencing —even in the absence of physical meetings — and, partially, outside the official IT systems. It is difficult to imagine that employees want to give up this new-gained work method autonomy once the crisis is over. After the BYOD (bring your own device) and shadow IT have challenged many IT departments over the years, the newly emerging DIY (do it yourself) work processes will for sure create headaches in compliance departments around the world. But the lack of standardization, compliance, and control is rewarded by creativity and engagement and, subsequently, increased corporate performance.

Employees decide when to work: Work schedule autonomy allows employees the discretion to decide when they want to conduct the work. As people have worked from home during the pandemic, many have found themselves needing to work at odd hours in order to balance the tasks of the household with those of the workplace. Specifically, many employees have found out that they have the capacity to orchestrate work and keeping schedules and deadlines – despite not necessarily fitting into the 9-to-5 template. Autonomy over work schedules has tripled during the pandemic – and it is expected that the future workplace needs to emphasize meeting business deliverables rather than working a fixed set of hours when measuring personal productivity. A BCG COVID-19 employee sentiment survey with over 12,000 respondents found that over 50% indicate that they want some flexibility in when they work in the future – and Zoom has stated that it has tallied a 700% increase in weekday evening meetings and a 2,000% increase in meetings in the weekend. All of this suggests that employees have decided when to work during the pandemic, and that they expect to continue to do so once we reach a new normal.

Consider how Silicon Valley tech companies have been forced to reconsider its ‘always-on(site)’ working culture. While they became famous for a non-stop 24-hour onsite work culture, employees are increasingly allowed to set their own work schedules. Companies such as Apple, Google, Facebook, LinkedIn, and Uber have new policies in place to help employees with managing their time while they work at home: Google, for instance, has issued a plan giving up to 14 weeks paid time off (or 28 weeks of half time off) to help care for loved ones – Facebook has introduced a similar model and offered flexible working hours – and Apple has similarly been proactive in providing more flexibility in how employees structure their worktime. While these efforts are put in place to address the emergencies unfolding in the current pandemic, it should be expected that they will evolve into a new pattern of working in Silicon Valley and beyond. A NBER study reports that working hours have been extended by 48 minutes on average (measured by email activities) but with overall less time allocated to meetings—thus indicating employee autonomy during working hours.

It should also be noted that employee discretion of how and when can be combined. In our research on autonomy during the pandemic, we’ve collaborated with Volvo Construction Equipment in Denmark, where such a how-when combination took place. Here, employees ‘on the floor’ took the initiative to cope with the pandemic and at the same time kept operations running. As a result, they restructured the work in the rep and prep shop (how) into two distinct shifts (when). By so doing, they maintained safe, and constant, operations – and they did so on their own, without managerial orders. Consequently, they decided how and when to do the job in the midst of the pandemic. 1

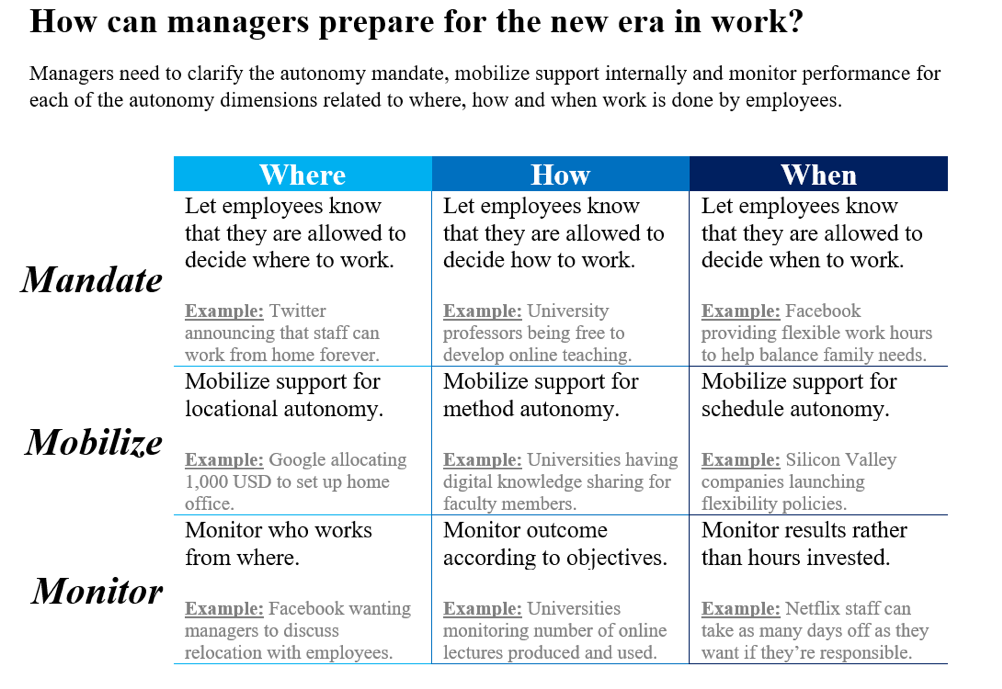

COVID-19 is not only changing what and where but also how and when we work. Consequently, it is imperative that managers adapt to this new era of work and prepare for how best to use it during and after the crisis. Below we provide recommendations for how managers can best take advantage of the shift to more autonomy in “how” and “when” both now and going forward – recommendations that are backed up by examples of managers currently working through these scenarios. Specifically, we suggest the following recommendations (See ‘How can managers prepare for the new era in work?’).

Mandate: First and foremost, managers need to be clear what the mandate is for employees to be autonomous. Twitter illustrated this perfectly for the ‘where’ dimension by announcing that their staff could work from home in perpetuity noting that “opening offices will be our decision – when and if our employees come back will be theirs”. Volvo Construction Equipment similarly demonstrated this capacity by being clear that floor workers were allowed to change how and when to work if they deemed this useful for securing ongoing operations in a secure manner. Most college and university professors were also provided a formal mandate to act as they saw fit when they had to transition their teaching to an online universe. Hence, clarifying the mandate is key.

Mobilize: Merely delegating decision rights is not enough to obtain success – managers also need to mobilize support internally in their organizations. Mobilizing support refers to both employee support and organizational support. For instance, when Facebook gave its staff better opportunities to decide when to work, they made opportunities executable by launching a paid leave model, mobilizing discussions between managers and staff on flexible hours and clarifying whether or not these actions make sense for the work situation that the employees find themselves in. Moreover, when universities transitioned towards online learning, they needed to mobilize support internally. Faculty needed to be on board to take on this new responsibility – but technical and knowledge sharing support also needed to be launched. For instance, The University of Florida has started a ‘Student Plaza’, where it is possible to connect with academic advisers and form study groups – and Pennsylvania’s Muhlenberg College has so-called ‘digital learning assistants’ who have remote drop-in hours to coach faculty and students to use online tools.

Monitor: Setting employees free does not preclude that managers monitor them. On the contrary, we’ve found that autonomy requires more, not less, active engagement from managers. For example, in terms of when to work, it requires that managers focus more on tracking results rather than hours invested when assessing individual productivity. However, when weekend meetings on Zoom rise by 2,000%, it is clear that managers also have a responsibility in monitoring if their employees can manage the newly gained freedom without feeling pressured to always be online. Here, companies such as Facebook have shown that frequent follow up on work time autonomy is important. Work method autonomy also needs to be monitored, as it is important that employees are held accountable for their autonomous actions. Netflix has made this a key value in their organization by incorporating a ‘freedom and responsibility’ principle in their culture. It’s also important to be cognizant of the fact that when you delegate responsibility it won’t necessarily be perfect to a start. When universities started to convert classes into a digital format, many deans explicitly used an “OK is good enough for now” mantra to evaluate the quality of online lessons.

The bottomline is that we’re all going to be affected by the current pandemic. Work as we know it is changing – and employers need to adapt to this new reality. Those who’ll master the where, when and how of autonomy will succeed in attracting skilled employees and achieving great results.

Our research draws on the combination of two ongoing areas of interest: (1) How companies deal with the COVID-19 crisis and (2) how companies deal with employee autonomy. Consequently, we combined these two research efforts to better understand the changes that COVID-19 brings to workplace autonomy.

For more on our work on the coronavirus crisis see:

For more on our work on employee autonomy see:

Personal communication with Jens Ejsing, Managing Director, Volvo Construction Equipment Denmark ↩

Spotlight

Sayan Chatterjee

Spotlight

Sayan Chatterjee

Spotlight

Mohammad Rajib Uddin et al.

Spotlight

Mohammad Rajib Uddin et al.