California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier academic management journal published at UC Berkeley

by Mokter Hossain and Steven A. Creek

Image Credit | NeONBRAND

Crowdfunding is a promising way for individuals and start-ups to raise funding from a large number of people, using an online platform to turn their dreams into reality. It is an alternative to conventional options such as angel investors, venture capital, and banks for securing funding. No doubt, it has emerged as a blessing for business ventures, charitable causes, or personal needs [1]. Crowdfunding involves three main types of actors – founders, platforms, and funders. Founders initiate crowdfunding campaigns, platforms provide necessary support to connect founders and funders, whereas funders provide the funding.

“The Present and Future of Crowdfunding” by Valentina Assenova, Jason Best, Mike Cagney, Douglas Ellenoff, Kate Karas, Jay Moon, Sherwood Neiss, Ron Suber, & Olav Sorenson

“The Prospects for Enlightened Corporate Leadership” by James O’Toole

The global crowdfunding market is surging. It drew 13.9 billion dollars in 2015 and is forecasted to reach one trillion dollars by 2025. Platforms like Kickstarter, Indiegogo, and GoFundMe have raised money for millions of ideas. However, with rapid growth comes an influx of problems. While bright stories of crowdfunding are more prominent, unethical behavior and fraud are abundant. It is essential to unveil the dark side of crowdfunding, both to have a balanced understanding of this phenomenon and to begin fixing the problems.

Crowdfunding has been misused for a range of reasons [2]. From fake cancer to phony funerals to counterfeit gadgets, the dark side of crowdfunding sometimes turns naive funders into victims. Despite the good intention of funders to help others, lack of transparency and loopholes jeopardize the reputation of crowdsourcing. Some of the more common frauds in crowdfunding include funding misapplication, impersonation, faked illness, and failure to deliver promised rewards [3].

Source: gamersheroes.com

Crowdfunding platforms are often blamed for their lack of due diligence regarding founders and crowdfunding projects. The most popular platform, Kickstarter, has been implicated in numerous frauds. Another prominent platform, GoFundMe, is liable for thousands of frauds, even prompting the spin-off website GoFraudMe, which compiles instances of fraud within crowdfunding. For example, the site tracks instances where founders run away with the raised funds or where specifications of the project may be misrepresented [4].

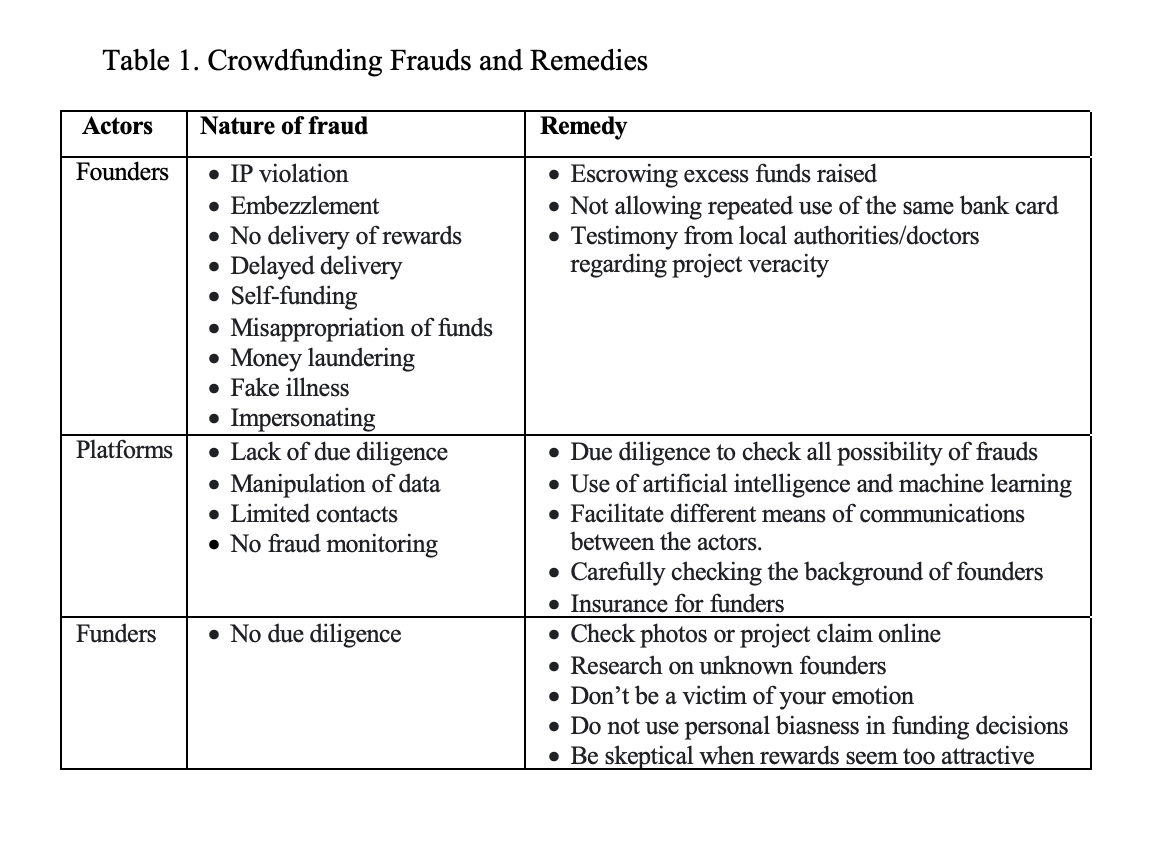

Several other types of fraud are prevalent in crowdfunding. First, crowdfunding opens the door for violations of intellectual property (IP) rights. This occurs when a campaign uses another person’s IP without permission. For example, Ron Forbes started a campaign on Indiegogo to raise money to produce the short film “DON’T MOVE”. During the campaign, the original film creator alerted about this fraud on Twitter and eventually got the campaign down. Second, crowdfunding has seen cases of payment fraud, investment fraud, embezzlement, or money laundering. Stolen credit cards are used to fund own campaigns. To increase success in all-or-nothing campaigns, founders often fund their own projects to boost the funding momentum despite rules against it. In other cases, funds are diverted for personal purposes. As many as 10% of funded campaigns on Kickstarter suffer from fund misappropriation. Third, some crowdfunding causes are questionable at best. For example, the license of a nurse was temporarily suspended due to his involvement in murdering two patients and injuring several others. He went to the GoFundMe platform to raise money to cover his legal fees and fight the case to restore his license. Thomas Lane, a police officer charged for the death of George Floyd, raised $750,000 for his bail via crowdfunding. While these issues plague crowdfunding in a general capacity, more problems arise within specific types of crowdfunding, such as rewards-based, equity, and donation-based as listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Crowdfunding Frauds and Remedies

Rewards-Based Crowdfunding.Rewards-based campaigns entice backers with early access to new products, collaboration regarding design, or other rewards. However, it is not uncommon for founders to delay rewards or provide no rewards at all. Reasons for this can include procurement problems, regulations, rewards complexity, shipping costs, or campaign cancellation. Delays can also occur due to unexpected volume – when founders raise far more money than anticipated. For example, when Altius Management’s Kickstarter campaign raised 60% more than their goal, the promised rewards were delayed since demand exceeded supply. Eventually, the Altius Management stopped communicating with the funders. A court later ordered Altius Management to recompensate the funders. Unfortunately, there is no established mechanism to track the founders. Funders are often left in the lurch.

Donation-Based Crowdfunding.Funders using donation-based platforms rarely expect anything in return. Campaigns for charities and medical issues are common on these platforms. Unfortunately, fraud is prevalent in this context as well. Numerous project founders fake illness to supplement income. For example, Jenny Cataldo claimed in her fraudulent campaign that she had terminal cancer and needed money for medical expenses. After raising over $23,000, a court investigation revealed her claim fake. Others have gone so far as to shave their heads to fake cancer, fabricate medical reports, or alter billing statements. Some use images of relatives or from online sources to make false claim. For example, photos from the online sources of a sick child or a pet are widely used to raise funding. Impersonating is an easy way to play with the emotion of the funders.

Equity-Based Crowdfunding.Entrepreneurial crowdfunding projects are typically in early stages of business and their failure rates are high. Therefore, equity crowdfunding is highly risky. Equity backers are not guaranteed a return even if the project is fully funded. Advocates of equity crowdfunding argue that online platforms provide adequate channels to interact between founders and funders to judge a venture before investment. In reality, this is rarely the case and information asymmetry abounds. For example, ZeekRewards lured in more than 900,000 victims, including 1500 locals and even sophisticated investors, with a promise of a 125% return on their investment. The CEO responsible for this 900 million dollar internet Ponzi scheme was sentenced 14 years in prison. However, equity crowdfunding in the real estate sector has lower risk as funders can easily do due diligence to check some basic facts, such as properties.

The long-term viability of crowdfunding and eliminating fraud go hand-in-hand. To reduce the regularity of this darkness, a collective effort from founders, platforms, and funders should be sought after.

Brighter Platforms.Arguably, the party with the greatest potential for brightening crowdfunding platforms are the platforms themselves. Platforms should regularly be screening for fraud—before, during, and after campaigns. A recent study argues that at least some portion of projects should be screened for fraud [5]. Other experts suggest that 90% of frauds can be identified by analyzing campaign descriptions based on machine learning classifiers. While some platforms use automation to identify fraud, artificial intelligence has not been widely applied despite its enormous potential.Screenings should take place not only within but also between platforms. Certain founders have been documented to use multiple platforms for the same project. Crowdfunding platforms don’t scan for such occurrences.

Due diligence should be increased by crowdfunding platforms. Prior to launching projects, platforms should verify the information provided by founders. During campaign creation and fundraising, a system of check and balance should be implemented to identify misleading or false product descriptions. After the campaign, platforms should have standards and policies regarding delayed or nonexistent delivery of rewards. Platforms currently argue that due diligence in preventing fraud is difficult for them to enforce. They leave the job to funders who typically have very little leverage. More due diligence to combat fraud at the platform level would clearly benefit funders in the short-term, but it would also help platforms in the long run by establishing trust with funders and founders alike.

Brighter Founders. Many founders put the proverbial cart before the horse by launching campaigns shortly after idea generation. Instead, founders should take actions to protect themselves. First, thorough research should take place in regards to funding requirements. Business plans of ideas should subsequently be shared with potential funders. Using milestones helps the crowd understand what the funds will be used for and how much is needed to accomplish different tasks. Second, for campaigns involving novel products, patent protection must occur prior to campaign launch. Placing a product prototype or a design on a crowdfunding platform exposes founders to imitation. This lesson was recently learned by the founder of Fidget Cube, who raised more than $6 million on Kickstarter to produce a small desk toy. Knock-offs of this product were available on Amazon for nearly one-third the price.

Brighter Funders. Funders also have a role to play in due diligence. Beyond the information provided by the founder and the platform, additional questions should be considered. What is the founder’s crowdfunding history? Is the amount requested reasonable? Does the founder have the skillset required to embark on this endeavor? Can this project be completed in the advertised time?

Funders also need to educate themselves on the contractual obligations of the founder and their minimal rights. For example, Kickstarter states that if projects are unable to deliver on promises, they may be subject to legal action by the backers. In extreme cases, funders have used the law to force fraudsters into partial rewards, repayment, or even bankruptcy.

Snyder, J.; Mathers, A.; Crooks, V.A. Fund My Treatment!: A Call for Ethics-Focused Social Science Research into the Use of Crowdfunding for Medical Care. Social Science & Medicine 2016, 169, 27–30.

Siering, M.; Koch, J.-A.; Deokar, A.V. Detecting Fraudulent Behavior on Crowdfunding Platforms: The Role of Linguistic and Content-Based Cues in Static and Dynamic Contexts. Journal of Management Information Systems 2016, 33, 421–455.

Zenone, M.; Snyder, J. Fraud in Medical Crowdfunding: A Typology of Publicized Cases and Policy Recommendations. Policy & Internet 2019, 11, 215–234.

Belavina, E.; Marinesi, S.; Tsoukalas, G. Rethinking Crowdfunding Platform Design: Mechanisms to Deter Misconduct and Improve Efficiency. Management Science 2020, 66, 4980–4997.

Ellman, M.; Hurkens, S. Fraud Tolerance in Optimal Crowdfunding. Economics Letters 2019, 181, 11–16.