California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier professional management journal for practitioners published at UC Berkeley Haas School of Business.

Dr. Yusaf H. Akbar

Image Credit | Ales Nesetril

US President Joseph Biden issued an executive order (EO) on antitrust policy in July 2021 declaring: “We’re now 40 years into the experiment of letting giant corporations accumulate more and more power. I believe the experiment failed.”[1]. Over that period, price-cost markups have tripled[2]; the rate of new business formation fell by fifty percent[3]; In three quarters of U.S. industries, concentration is higher than two decades prior[4] and wages have decreased by more than fifteen percent in key sectors of the US economy[5]. The Biden Administration argues these are prima facie evidence of the need for action in antitrust policy. The EO launches seventy-two actions to address these concerns. The EO orders a “whole-of-government competition policy” requiring coordination of federal agencies that influence competition policy. This, the EO claims, is to address “overconcentration, monopolization, and unfair competition in the American economy”[6].

“’Digital Colonization’ of Highly Regulated Industries: An Analysis of Big Tech Platforms’ Entry into Health Care and Education” by Hakan Ozalp, Pinar Ozcan, Dize Dinckol, Markos Zachariadis, & Annabelle Gawer

“How to Compete When Industries Digitize and Collide: An Ecosystem Development Framework” by Michael G. Jacobides

In this paper, we analyze potential impacts of the EO on companies, offering guidance on how to respond. The EO is the most important evolution in US antitrust since the Reagan administration, inspired by the work of Robert Bork[7], rejected interventionist competition policy of previous administrations. If the EO is comprehensively implemented, the implications for US firms and the economy are significant. Given the US’ leadership role in antitrust policy worldwide, it may also encourage a more interventionist approach to competition policy in other countries and jurisdictions.

The EO has three key implications for business.

Half a century of antitrust traditions by the federal judiciary do not change overnight. The federal judiciary may challenge aspects of the EO shielding companies from some of its far-reaching aspects. A recent decision of a US federal court to dismiss a lawsuit that was seeking to require Facebook to divest Instagram and WhatsApp supports this. The judge stated the complaint was “legally insufficient” failing to show that Facebook had monopoly power.[9]

Our discussion is organized as follows. First, we examine the origins of the current “antitrust counterrevolution”[10] that has influenced the formulation of the Biden EO. Second, we offer guidance on how firms should respond to key areas of the EO. Third is a conclusion considering how the EO may impact antitrust worldwide.

As 21st century industry consolidation has risen there has been a rethink of antitrust policy[11]. Three antitrust scholars have played a key role in this rethink – Jonathan Kantar, Lina Khan, and Tim Wu. In 2003, Wu coined the phrase ‘network neutrality’[12] serving as the basis for thinking on regulation of internet access. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) enshrined net neutrality into its rules, but the Trump administration later repealed them[13]. Upon Biden’s election, Wu was appointed to the Administration as Special Assistant with responsibility for Technology and Competition Policy. Net neutrality is thus likely to make a comeback.

Lina Khan’s 2016 Yale Law Journal paper on Amazon’s near monopoly of online retail argued for a reconsideration of US antitrust policy.[14] She argued it was insufficient to only consider price effects of anti-competitive conduct: while Amazon offers low prices to customers, Amazon’s integration across business lines (own online retail, marketplace platforms, media etc.) produced anticompetitive outcomes through cross-subsidy and predatory pricing. She argued that this analysis could be applied to any industry where network effects, such as those possessed by Amazon, were important. She proposed the restoration of pre-1980s antitrust enforcement applying ‘common carrier’ rights to firms active on platforms (i.e., net neutrality à la Wu). In March 2021, President Biden nominated her to be the Chair of the FTC and she was later confirmed by the US Senate in June 2021. Facebook immediately called for her recusal on any antitrust investigations that involved the company, questioning her impartiality.[15]

Lastly, the Biden Administration has nominated Jonathan Kantar to serve as assistant attorney general in the DOJ Antitrust Division. Kantar is an outspoken critic of Silicon Valley technology firms[16]. Kantar, Khan and Wu are adherents of the ‘New Brandeis’ antitrust movement. They argue that the focus of US antitrust law be broadened beyond competition and price analysis by focusing on reducing economic inequality, strengthening consumer protection, and increasing wage growth. All three appointments to the Biden administration reinforce the new antitrust posture in the Biden EO.

Executive orders issued by US Presidents are often substitutes for Congressional legislation.[17] By contrast, the Biden antitrust EO reactivates the enforcement of existing legislation creating a potentially enduring impact of the EO as future presidents would need Congress to pass new legislation to halt federal action called for in the antitrust EO.

Three characteristics of the EO stand out. First, it covers both substantive and procedural aspects of antitrust policy. Second, the EO considers monopoly abuse not just in product/service markets but also addresses monopolistic impacts in factor markets e.g., wages. Third, the EO takes a government-wide approach to competition policy asking all relevant federal agencies to explicitly consider competition policy impacts in their actions.

EO implementation

Research has considered the evolution and effectiveness of Presidential Executive Orders[18] considering several aspects of executive orders and factors influencing their implementation. First, the fewer the agencies involved and the clearer the policy direction, the greater the likelihood of implementation[19]. When action is required by one agency (typically the FTC) and there is existing legislation available, implementation probability is high. Where complex actions of multiple federal agencies in concert is required policy implementation probability is medium. Absent legislative provisions already on the statute book, policy implementation is medium.[20] Absent existing legislation, implementation probability is low.[21] Second, support among the electorate for executive action matters. The more popular an EO, the more likely a US President will issue it[22]. A President is emboldened where consistently high levels of concern expressed about corporate power in public opinion is present.[23]

There is a high probability of procedural actions by federal agencies arising from the EO. Activist roles for the FTC and DOJ in implementing existing statutes such as Merger Control and revising federal guidelines looks likely. By contrast, substantive policy implementation is likely to be mixed. We find high probability for actions making use of antitrust prohibitions in current US law to pursue firms in pharmaceuticals and agricultural equipment. In the US pharmaceutical industry new molecule pharmaceutical firms pay generic producers to not produce drugs for years after patent expiry. These practices will likely be targeted by the FTC[24],[25]. In agricultural equipment repair and after sales service markets, the FTC is expected to tackle exclusive distribution and aftermarket practices.

Medium to high implementation probabilities are also noteworthy. The Biden administration emphasizes how the federal government plays a role in improving labor market conditions for workers considering antitrust law enforcement as a potential remedy. The FTC has several legislative tools to tackle restrictive business practices which depress wages such as non-compete clauses. Compared with procedural and technocratic issues where the FTC can act using existing legislation outside of public spotlight, wages are very much an ‘above the radar’ issue. Actions taken by the FTC and related federal agencies may provoke attempts by Congressional actors supportive of corporate interests and limit federal agency efforts.

Finally, two specific initiatives with low to medium probabilities of policy implementation: federal procurement to involve more small businesses (low) and action by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) to promote account portability for retail financial service customers (medium) are relevant. We attribute low probability of policy implementation for small business opportunities in federal procurement as it is a complex multi-agency process requiring Congressional budgetary action. While the CFPB was created to strengthen financial consumer rights, robust bipartisan Congressional support for the financial services sector may slow down progress through increased congressional oversight of the CFPB. Analogously, the call in the EO to lower pharmaceutical drugs prices or combatting rising costs of healthcare services is largely aspirational requiring legislative action and would induce considerable resistance in the US Congress.

An Action Agenda for Executives

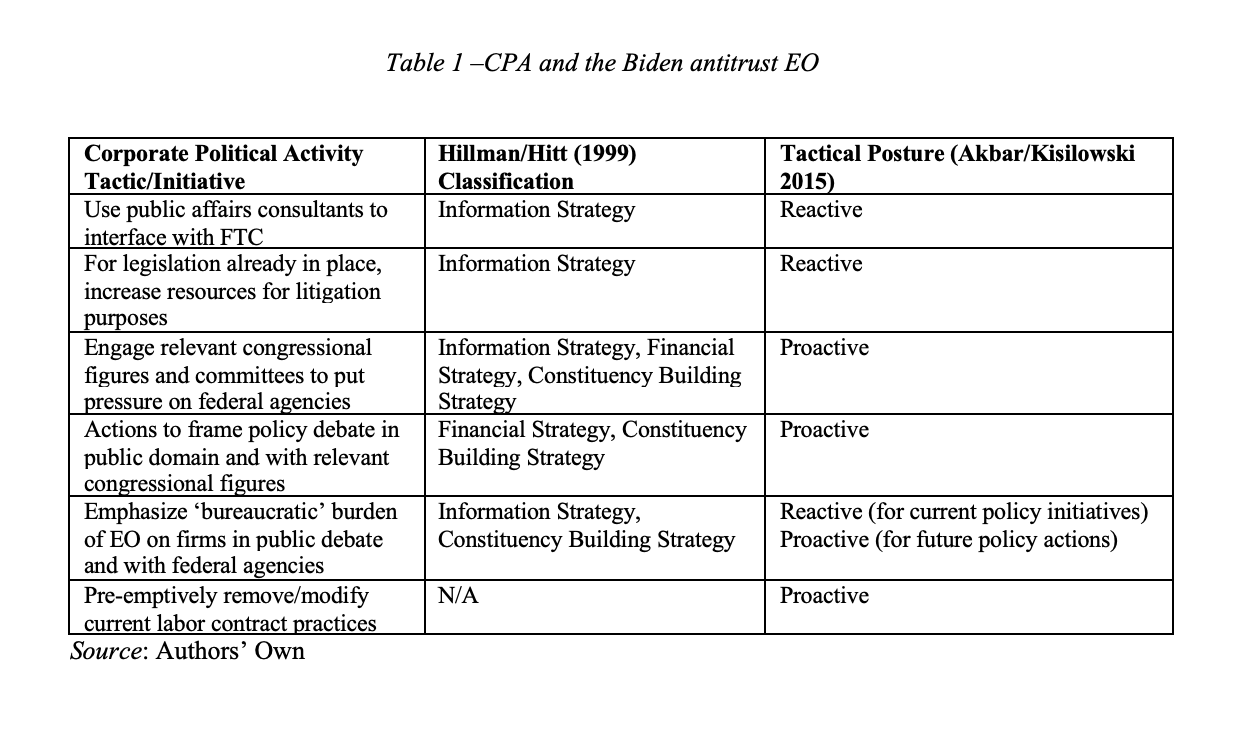

A fuller discussion of the field of corporate political activity (CPA) (or non-market strategy) is beyond this paper but a recent definition captures it well: “Corporate political activity is defined as a corporation’s efforts to influence political processes […] Forms of corporate political activity include lobbying, donating money to candidates and parties, corporate social responsibility, private regulation, and corporate philanthropy”[26]. Hillman and Hitt identified three categories of CPA: information strategies, financial strategies, and constituency-building strategies.[27] We adopt this taxonomy. In addition we draw on Akbar and Kisilowski to categorize CPA as being either proactive or reactive.Proactive actions shape emerging public policy while reactive ones limit the negative impact of the implementation of existing policy.

Table 1 categorizes corporate actions in response to the EO using these two related taxonomies. Executives should adopt a proactive posture where policy is relatively underdeveloped. Examples of this include healthcare pricing/affordability or government procurement. Technocratic expertise (information strategy), political contributions to Congressional politicians (financial strategy) and firm-level and industry association level information campaigns (constituency-building strategy) can be used to shape public debate and policy agendas.

Where policy implementation is likely, CPA should seek to limit change through information strategies directed at federal agencies supported by financial strategy and constituency-building strategies. Litigation as CPA is also important. In the areas of around merger control and regulation of restrictive business practices, executives should strengthen their legal counsel units with new hires or engage law firms with a strong reputation in antitrust. Where policy implementation probability is medium, both proactive and reactive CPA should be used. In the area of restrictive labor practices, firms should pre-empt federal action by unilaterally modifying them. This may gain support in Congressional circles and broader society by demonstrating corporate willingness to find common ground with labor unions.

A Final Caveat: The Role of the Federal Judiciary

Decades of judgements from the federal bench carry weight in the US antitrust legal landscape. There are many judges who prefer less interventionist antitrust enforcement and who remain on the federal bench. Using the Federal courts to slow changes from the EO is an option for companies. Companies and industry associations should also be prepared to challenge elements of the EO at the US Supreme Court if necessary.

In contrast with early policy responses and initiatives of the Biden administration (COVID19 recovery or federal voting rights legislation), proposed changes to the way the US handles competition policy is largely proceeding below the political radar. However, the ‘low politics’[29] of antitrust imply significant financial and strategic implications for corporates and their executives. Our study undertook the following tasks. First, we contextualized the EO within current competition policy trends being led by ‘New Brandeisian’ antitrust scholars and experts. Second, we assessed probabilities of policy implementation of policy initiatives in the EO. Lastly, we identified how companies could develop CPA in response. Companies and their executives should be a complex combination of pre-emption and defensive response on a policy-by-policy basis as follows.

While beyond the scope of this paper, significant changes in enforcement practices and procedures of US antitrust have an impact on the rest of the world. A return to pre-1980s antitrust may lead to convergence with the European Union (EU). This could facilitate greater antitrust cooperation with the EU. US competition policy as articulated by the EO may also herald a more interventionist antitrust posture for other competition policies worldwide. For global firms, this should be the focus of consideration both on an analytical and prescriptive basis

[1] Grim, R. (2021), Antitrust Makes a Comeback, Deconstructed Podcast, July 16, 2021, accessed at https://theintercept.com/2021/07/16/deconstructed-podcast-antitrust-zephyr-teachout/ (last visited on August 2, 2021).

[2] Basu, S. (2019). Are price-cost markups rising in the united states? a discussion of the evidence. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(3), 3-22.

[3] BakerHostetler (2021). President Biden’s Executive Order: A Revolution in Antitrust Enforcement? July 15, 2021. Accessed at https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/president-biden-s-executive-order-a-5558231/. (Last visited, July 28, 2021).

[4] Philippon, T. (2019). The economics and politics of market concentration. NBER Reporter, (4), 10-12.

[5] De Silver, D. (2018). For most U.S. workers, real wages have barely budged in decades. Pew Research Center, August 7, 2018. Accessed at https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/08/07/for-most-us-workers-real-wages-have-barely-budged-for-decades/. (Last visited July 26, 2021).

[6] The White House (2021), “Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy” Briefing Room, July 9, 2021. Accessed at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/07/09/executive-order-on-promoting-competition-in-the-american-economy/. (Last visited August 2, 2021).

[7] Bork, R. (1978). The Antitrust Paradox: A Policy at War with itself. New York: Basic Books

[8] US Federal Trade Commission (2020). Remarks of Commissioner Rebecca Kelly Slaughter at FTC Workshop on Non-Compete Clauses in the Workplace. January 9, 2020. Accessed at https://www.ftc.gov/public-statements/2020/01/remarks-commissioner-rebecca-kelly-slaughter-ftc-workshop-non-compete. (Last visited July 25, 2021).

[9] Bartz, D. & Elizabeth Culliford (2021). Facebook hits $1 trillion value after judge rejects antitrust complaints. June 29, 2021, Reuters. Accessed at https://www.reuters.com/technology/us-judge-tells-ftc-file-new-complaint-against-facebook-2021-06-28/. (Last visited July 24, 2021).

[10] Khan, L. M., & Vaheesan, S. (2017). Market power and inequality: The antitrust counterrevolution and its discontents. Harvard Law & Policy Review, 11, 235.

[11] Evans, D. S. (2003). The antitrust economics of multi-sided platform markets. Yale Journal on Regulation, 20, 325; Manne, G. A., & Wright, J. D. (2011). Google and the limits of antitrust: The case against the case against Google. Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy, 34, 171; Newman, J. M. (2019). Antitrust in digital markets. Vanderbilt Law Review, 72, 1497; Parker, G., Petropoulos, G., & Van Alstyne, M. W. (2020). Digital platforms and antitrust. Available at SSRN 3608397; Subramaniam, M., Iyer, B., & Venkatraman, V. (2019). Competing in digital ecosystems. Business Horizons, 62(1), 83-94.

[12] Wu, T. (2003), Network Neutrality, Broadband Discrimination. Journal of Telecommunications and High Technology Law, Vol. 2, p. 141, 2003

[13] Reardon, M. (2017). What you need to know about the FCC’s net neutrality repeal. December 14, 2017. CNET. Accessed at https://www.cnet.com/tech/services-and-software/fcc-net-neutrality-repeal-ajit-pai-what-you-need-to-know/. (Last visited July 26, 2021).

[14] Khan, L. M. (2016). Amazon’s antitrust paradox. Yale Law Journal, 126, 710.

[15] Kendall, B. (2021). Facebook Seeks FTC Chair Lina Khan’s Recusal in Antitrust Case. July 14, 2021. Wall Street Journal (online edition). Accessed at https://www.wsj.com/articles/facebook-seeks-recusal-of-ftc-chairwoman-in-antitrust-case-11626267605. (Last visited August 2, 2021).

[16] Hirsch, L. & David McCabe. (2021). Biden to Name a Critic of Big Tech as the Top Antitrust Cop. July 20, 2021. New York Times (online edition). Accessed at https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/13/opinion/biden-executive-order-antitrust.html. (Last visited July 23, 2021).

[17] Johnson, K. R. (2017). Immigration and civil rights in the trump administration: Law and policy making by executive order. Santa Clara Law Review, 57, 611.

[18] Mayer, K. (2002). With the stroke of a pen: Executive orders and presidential power. Princeton University Press.

[19] Kennedy, J. B. (2015). “‘Do This! Do That!’and Nothing Will Happen” Executive Orders and Bureaucratic Responsiveness. American Politics Research, 43(1), 59-82.

[20] Deering, C. J., & Maltzman, F. (1999). The politics of executive orders: Legislative constraints on presidential power. Political Research Quarterly, 52(4), 767-783.

[21] Rudalevige, A. (2021). 1.“On My Own”? Executive Orders and the Executive Branch. In By Executive Order (pp. 1-24). Princeton University Press.

[22] Christenson, D. P., & Kriner, D. L. (2019). Does Public Opinion Constrain Presidential Unilateralism?. American Political Science Review, 113(4), 1071-1077.

[23] Riffkin, R. (2016). Majority of Americans Dissatisfied with Corporate Influence. January 20, 2016. Gallup News. Accessed at https://news.gallup.com/poll/188747/majority-americans-dissatisfied-corporate-influence.aspx. (Last visited July 25, 2021).

[24] Fox, E. (2017). How pharma companies game the system to keep drugs expensive. Harvard Business Review (April 6, 2017), accessed at https://hbr. org/2017/04/how-pharma-companies-game-the-system-to-keep-drugs-expensive (last visited on August 1, 2021).

[25] Feldman, R. (2021). The Price Tag of ‘Pay-for-Delay’. Available at SSRN 3846484.

[26] Bernhagen, P. (2020), Corporate Political Activity. Chapter 1 in Bitoni, A., Harris, P., Fleisher, C. S., & Binderkrantz, A. K. (2020). The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Interest Groups, Lobbying and Public Affairs. London: Palgrave, p.1.

[27] Hillman, A. J., & Hitt, M. A. (1999). Corporate political strategy formulation: A model of approach, participation, and strategy decisions. Academy of management review, 24(4), 825-842.

[28] Akbar, Y. H., & Kisilowski, M. (2015). Managerial agency, risk, and strategic posture: Nonmarket strategies in the transitional core and periphery. International Business Review, 24(6), 984-996.

[29] Keohane, R. O., & Nye Jr, J. S. (1973). Power and interdependence. Survival, 15(4), 158-165.

Spotlight

Sayan Chatterjee

Spotlight

Sayan Chatterjee

Spotlight

Mohammad Rajib Uddin et al.

Spotlight

Mohammad Rajib Uddin et al.