California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier academic management journal published at UC Berkeley

by Alfred A. Marcus and Mazhar Islam

Image Credit | Redd

Disproportionately old nations such as Japan, Germany, and the U.S. start with many advantages, but they suffer from demographic deficits that arise because of rapid decline in their working-age population. As these deficits rise, they must find the resources to care for the elderly effectively while nurturing the young adequately. To manage, they need some combination of technological innovation that advances productivity with greater automation, and liberal immigration policies. Firms in these nations also have to adapt to new realities and reorganize their operations for long-term competitive advantages.

“Global Clusters of Innovation: Lessons from Silicon Valley” by Jerome S. Engel

Disproportionately old nations have demographic deficits because they have small working-age populations (15 to 64 years old) relative to the elderly. These deficits create unusual threats and may bring into being inflections and tipping points to which business must adapt and reorganize. What are the changes businesses should make? How should they innovate? In what ways must they adapt to these realities?

Seven of the world’s nations with the highest demographic deficits are Japan, Germany, Spain, Taiwan, Russia, the United States, and China. Among them, China may be aging faster than its economy is growing. It could become old before it becomes truly wealthy. Global businesses that are heavily dependent on China are already experiencing shrinking markets for goods and services, and rising manufacturing costs due to labor shortages. With rapid aging and fewer working people, old nations may not have the resources to care effectively for the elderly while nurturing the young.

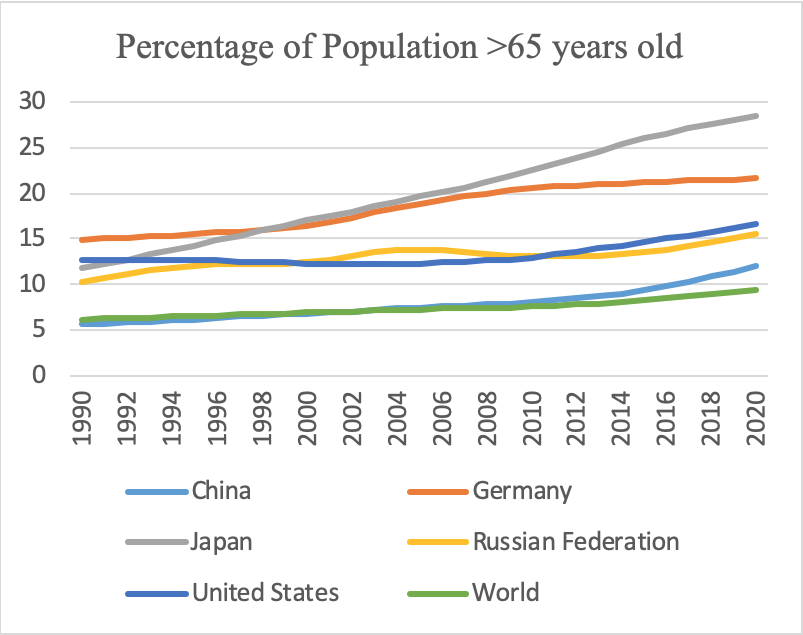

High levels of elderly dependency have reached critical states in many nations. The UN projects that, to the extent the world population is likely to grow, it will grow among people above 65 years in age. Similarly, the EU predicts that by 2025 there will be fewer than three employed persons for each retired person in the region. In Spain, about 9% of the country’s GDP went to entitlements for the aged, while education spending fell below 5% of GDP in 2015. Many countries already have skilled labor shortages because of an aging workforce. Figure 1 below shows the progression of aging in major old nations.

Figure 1: Major Aging Nations

These trends are important. Consider the quotation below from an interview with Catherine Keating, CEO of BNY Mellon’s Wealth Management Group. Keating was referring to her firm’s forecast for the decade that starts in 2020:

“… one of the things … about the next 10 years is … that market returns are going to be lower … (the) major reason for that … is that all of the largest economies in the world are aging at the same time. China, Europe, Japan, the United States. And we know what happens when an economy has aged. Inflation tends to go down, interest rates tend to go down … GDP growth tends to go down, and market returns tend to go down … actually, we’ve been seeing that through the whole 21st century inflation has been coming down. Interest rates have been coming down. GDP growth has been coming down. And market returns have come down …” 1

Keating attributes these weak economic outcomes to demographic changes.

Goodhart and Pradhan (2020) in their book The Great Demographic Reversal,2 suggest instead a rapid increase in inflation as nations age. The primary reason is a labor shortage – with fewer working people available, the cost of labor must rise, bringing with it unanticipated inflation.

However, societies with a disproportionate number of older people are exposed. The reason is the percentage of working people well positioned to support a dependent population is relatively small. Such societies may be prone to long-term stagnation in which inflation rises and GDP falls. Disproportionately old societies consume more than they produce.3 In these societies, output tends to go down. As more people age, a society’s standard of living is likely to fall if the society does not plan for coping with this eventuality.

Two major policy remedies for aging’s liabilities are liberal immigration and investment in technological innovation. However, both have limitations. Immigration, while it may foster economic growth because of an influx of workers, has stirred political debate and opposition in nearly every country in the world. Technological innovation may not advance at a rapid enough pace to increase productivity sufficiently to compensate for fewer workers.

Immigration. The U.S. anti-immigration polices under the Trump administration kept talented immigrants from coming to the U.S. and resulted in a lessening of the nation’s technological leadership capabilities. Immigrants also were coming in somewhat lower numbers to the U.S. because they perceived less economic opportunity. Even if immigrants came to the U.S., they faced low-paying jobs, little mobility, and bigotry; and the same fate, sadly, was likely to affect their children. To many of them, the American dream seemed out of reach.

Anti-immigration views gave rise to right-wing political parties in Europe. For instance, in Germany the Alternative for Germany (AfD) was the first far-right group to win seats in parliament in more than six decades. Its co-leader Alexander Gauland calls for an aggressive battle against an “invasion of foreigners.” After winning a third term in office in 2018, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban said the victory gave Hungarians “the opportunity to defend themselves and to defend Hungry.”4 Orban openly warned the threat of immigrants as “a Europe with a mixed population and no sense of identity.”

In the case of the U.S., immigrants are better educated than the native population. In 2018, more than 45% of recent immigrants had bachelor degrees or higher compared to only 32% of native-born Americans. Emma Lazarus’ famous poem on the Statute of Liberty declared, “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, the wretched refuse …” However, the immigrants who come to the U.S. in the 21st century on average are neither tired nor poor but talented and motivated.5 Bi-partition support is vital for pro-immigration policies in the U.S. Considering the dire situations in most EU nations, Japan, China and elsewhere, the governments of these nations have to reconsider their immigration policies so that they can balance the shortfall of the working age population with healthy inflows of immigrants from youthful nations.

Technological Innovation. Without effective immigration, countries’ only major remedy for aging is to raise productivity through technological innovation and therefore the pressure to make technological advances throughout the world has never been greater. Without a healthcare miracle, rich countries with aging populations are going to be burdened with exceptionally high healthcare costs. Countries experiencing rapid aging have tried to adapt by introducing productivity enhancing technologies such as industrial robotics.

In Japan, high-technology robots are increasingly taking over tasks from human beings. Death rates in Japan started to exceed birth rates in the first decade of the 21st century, which brought to the forefront many problems of caring for the elderly. Japan’s public debt in comparison to GDP, largely as a consequence, far exceeds that of any other country. Without much immigration into the country, it must depend on technology. Japan, therefore, has been a technological leader in caring for the elderly. Reliance of technology is essential because the country never has been hospitable to immigrants. Because of low fertility, the country’s population is expected to dip by 20% to 105 million by 2050.

Well aware of the issue, the Japanese government has undertaken initiatives to address it. The government has tried to get more women to enter and stay in the workforce. It has begun large-scale campaigns to persuade them to remain at work after pregnancy. Another action is parliamentary debate if the country should permit additional immigrants – the purpose would be mainly for agriculture, construction, and caring for the elderly.

The Japanese government has proposed to raise the retirement age and the age when people can start drawing their pensions; to lower medical costs for the elderly by encouraging older people to exercise and keep healthy; and to change deductibles on medical insurance. Given the scope of the problem, the overall results of these measures have not amounted to much. Japanese economic growth in comparison to other developed countries continues to be low.

Like Japan, China has been investing heavily in technological innovation with a special focus on artificial intelligence and robotics. China’s State Council issued the New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan (AIDP) in 2017.6 Although the plan is to aid China’s ambitious defense strategy and to reduce dependence on foreign technologies, the huge investments in the sector will result in productivity enhancing technologies directly or through spillovers. Governments of aging nations elsewhere have to follow similar strategies and substantially increase productivity enhancing technologies to compensate for shrinking working-age population.

But aging is not just a threat. Trying to anticipate what is likely to come next, many global companies are focusing on the opportunities. The year 2018 was a milestone in that the number of people in the world over the age of 65 surpassed those less than the age of 5, a trend that was moving forward quickly.

Many companies therefore launched new products to meet the needs of the elderly. Danone, for instance, set up a healthy-aging unit to examine how nutrition impacts cognition and mobility. Nestlé shifted the focus of its health sciences unit from food products to the prevention of disease and aiding people with recovery. It dedicated about 20% of this division’s budget to aging. IKEA started to sell chairs with higher seating that make it easier to get up, footstools to aid blood circulation, and grippers to unscrew lids for older people. Procter & Gamble sold a special razor for caregivers in nursing homes. L’Oréal was focusing on the fact that older people worry about wrinkles and spend disproportionately on skin care.

Other firms like Colgate Palmolive were developing products that alleviated young people’s concerns about the telltale signs of aging teeth.7

There were many business opportunities in the areas of disease detection and prevention and in providing care for the elderly. A higher portion of GDP has to be spent on pensions and healthcare as opposed to investment in education and infrastructure. Because of the shift, there is increased opportunity to supply goods and services the elderly vitally need, including medical devices, pharmaceuticals, cures for Alzheimer’s disease, care-giving services, and recreational activities geared toward the elderly.

Markets for the elderly, therefore, are large in elderly dependent countries, and they have the potential for rapid growth. Business leaders can help an aging population deal with disorders like dementia, stroke, chronic pulmonary obstruction, and vision impairment. They can be involved in the creation of much needed treatments for cardiovascular disease, cancer, respiratory, and other disorders. Countries with aging populations are also ripe for innovation in areas like remote medical communication, mental acuity training, techniques for post-acute illness transitions, and end of life planning.

Another lucrative possibility is new markets for automobile safety features such as infrared night vision, lane departure warnings, blind spot detectors, and automatic parking. Most of the automakers investing in autonomous cars are betting on a large senior citizen market. The new products that businesses can create because of rapidly growing elderly populations are nearly endless.

Although business leaders may perceive plentiful opportunity in aging nations, they also are likely to recognize that creating a successful business in these countries will be challenging. In aging nations there is likely to be a shortage of qualified workers. When businesses find people to fill these roles, they are likely to face higher labor costs, a situation many countries including the U.S. and China currently confront. Japan has more job openings than job seekers; about 1.6 jobs have been available for each person trying to find one. In the U.S., the current ratio is about one job per 0.8 workers, a deficit that is likely to grow in the future. The long-term concern with unemployment is likely to be replaced with a concern about labor shortages. In the U.S., as elsewhere, labor force growth is expected to fall-off. Not only will it grow slowly, but because older people are living longer, those who are working will be burdened by a higher number of elderly to support for long periods of time. Aging makes it challenging for countries to avoid imposing a large burden on the young, while providing a decent standard of living for the old.

Governments in countries with elderly populations have few options. In the trade-offs they must make between the old and the young, the young will often come up empty. Already the old in the U.S. control much more of the wealth compared to the young, a situation that is much different than it was a decade earlier.

What should governments do when they face this dilemma? Do they lower benefits to senior citizen and raise retirement ages? Raising the retirement age is likely to lead to political and social unrest. For instance, the French government had to scrap a plan to increase the retirement age from 62 to 64 after tens of thousands of anti-government protestors stormed the streets in 2018.

The takeaways are that at one time in history, a main global concern was with excessive fertility. However, as countries became more affluent and birth rates in many countries fell precipitously, the opposite problem has surfaced. In many countries, the fertility rate has fallen far below the replacement rate of 2.1 lifetime births per woman. In Japan, Germany, and Italy, it is about 1.4. In Hong Kong, it is about 1.1, meaning that within next 20 to 30 years its population is destined to decline by about one half unless government takes drastic initiatives to increase immigration and incentivize people to have more children.

Insufficient Preparation. Most countries have been making insufficient progress in preparing for global aging and old-age dependency. The lack of these countries’ preparation could have serious and long-lasting negative effects on the global economy and the firms that operate within them.

The impacts on countries falling working-age populations are profound. First, a shortage of labor will command higher pay, which is likely to result in an uptick in inflation. Second, economic growth, which arises from having more workers and their being more productive, may slow. A country with fewer workers has to increase its productivity rapidly, or else it faces diminishing growth. At best, it can maintain the same level of economic activity. Third, there will be less demand for products and services.

Without increases in productivity, or delays in the age of retirement, countries with fewer workers will not grow rapidly. Were there to be another economic shock like the great recession of 2007–08 or some other unexpected event like the COVID-19 pandemic, it will be challenging for countries with declining workforces to achieve a high level of growth. Both local and multinational firms will be negatively affected as a result.

The Workforce. In the U.S., as indicated, the number of jobs already is exceeding the number of job seekers, a development that exists because the number of elderly has been rising and immigration has been slow. Firms have to be prepared to increase salaries to retain quality human capital. They will have to attract employees who have traditionally remained outside the workforce. For instance, they may need to extend training programs or collaborate with higher education institutes and vocational training centers to develop a robust workforce. Recent examples of this practice include Google’s Grow with Google Career Certificates program offered in collaboration with Coursera.

Immigration. Immigration is the sensible way to replenish lagging working-age populations. However, until now, immigration at the scale needed to make a significant dent in the problem has been politically unfeasible in most countries. Firms in aging nations have to be proactive in pursuing policymakers for more liberal immigration policies. In the U.S., the Business Roundtable, an association of leading CEOs, has been vocal in promoting pro-immigration policies. The alternative, to persuade citizens to have more babies, or to incentivize them with monetary rewards, is a far slower and less certain way to approach this problem. Firms operating in countries with low birthrates can provide incentives such as longer parental leaves and launch programs to hire women with smaller children to encourage people to have more children.

One silver lining of reduced growth in aging countries may be less negative environmental impact. Reduced growth boosts efforts to lower greenhouse gas emissions, but this reduction may be accompanied by declines in food, water, and energy consumption, and lower living standards. Therefore, technological innovation that is good for the planet and good for the corporate bottom line should be a high priority. In short, what is needed in aging nations, comes down to spurring technological innovation to supporting immigrants so that the world’s economy can better cope.

Goodhart, C. and Pradhan, M., 2020. The Great Demographic Reversal. Springer International Publishing.

Lee, R.D. and Mason, A., 2011. Generational economics in a changing world. Population and Development Review, 37(s1), p.115.

Engel, J.S., 2015. Global clusters of innovation: Lessons from Silicon Valley. California Management Review, 57(2), pp.36-65.

Roberts, H., Cowls, J., Morley, J., Taddeo, M., Wang, V. and Floridi, L., 2021. The Chinese approach to artificial intelligence: an analysis of policy, ethics, and regulation. AI & SOCIETY, 36(1), pp.59-77.

Marcus, A. and Islam, M., 2021. Demography and the Global Business Environment. Edward Elgar Publishing.