California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier academic management journal published at UC Berkeley

by Mokter Hossain

Image Credit | Glenn Carstens-Peters

In the third quarter of 2021, global crowdfunding investment reached $160 billion. Crowdfunding is a relatively recently emerged phenomenon to raise funding from individuals for nascent business ideas. It is considered as an alternative source of funding for start-ups but copycats of crowdfunding ideas are a serious threat to these start-ups (Hossain and Creek, 2021). Fundraising campaigns on crowdfunding platforms, such as Indiegogo and Kickstarter reach millions of people including fraudsters. Start-ups need to signal quality to increase the funding success in their crowdfunding campaigns (Mollick, 2014). Hence, they display the products along with their operating mechanisms and functions in the crowdfunding campaigns to signal quality to convince the potential funders. However, such detailed display gives fraudsters opportunities to copycat. For example, Chinese factories and designers look for the next promising products to turn into copycats. They can assess the strengths and weaknesses of crowdfunding start-ups and glean information to ascertain how quickly they can enter the market. Longer production times or delivery delays can likewise signal that the entrepreneurs are novice and will likely to have limited resources to protect their ideas or legally stop copycats. Many such products are not patented but it is difficult to protect even patented products as the patent may not give global coverage or even if it gives, it is difficult for start-ups to fight the fraudsters who copy the products. Moreover, most start-ups are not well familiar with the sources of raw materials, manufacturing challenges, and distribution channels at the time of crowdfunding. Their philosophy is to explore these things after securing the funding. Fraudsters instantly steal ideas from crowdfunding platforms, quickly come up with copycats and reach the market well ahead of original start-ups. Thus, fraudsters ruin the business potential of start-ups. How to protect product ideas that are used for crowdfunding is an important question.

“Unveiling and Brightening the Dark Side of Crowdfunding” by Mokter Hossain and Steven A. Creek

Some Chinese firms produce products rapidly especially when products do not have technological complexities. For example, the Fidget Cube became one of the top most funded projects with about a $6.5 million pledge from 154926 backers against its only $15,000 goal. It is a desk toy for anyone who enjoys fidgeting. Someone from China saw this campaign and developed a similar product with the brand name Stress Cube, which made $34, 5000 in the first two months. The following images show the Fidget Cube and its copycat Stress Cube.

Fidget Cube (left) Stress Cube (right)

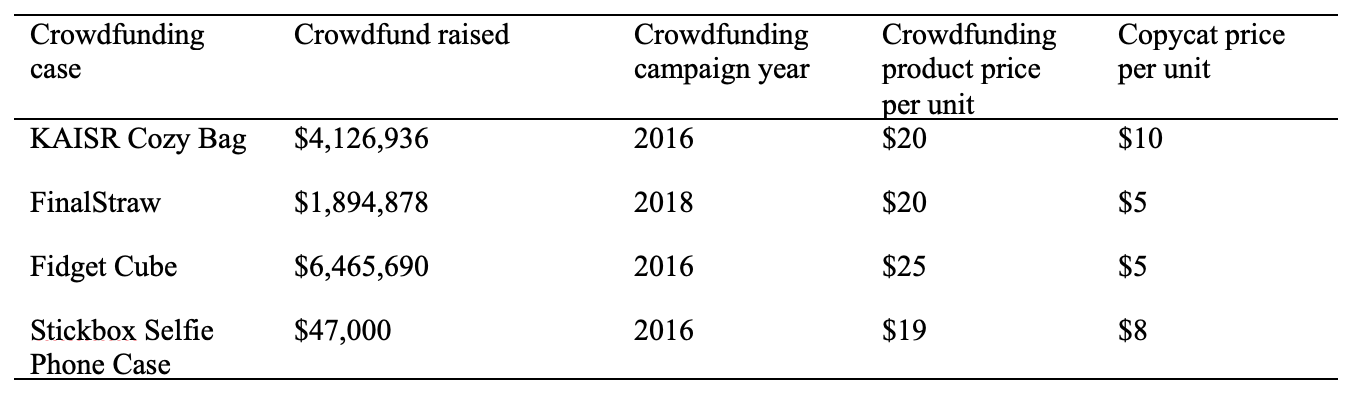

A 24-year-old Chinese serial fraudster copied products such as Fidget Cube and Cozy Bag and successfully beat the original ideas by reaching the market much faster. For example, copycats of Stress Cube and Cozy Bag were widely available long before the originals were to be manufactured. With digital tools, people find trending campaigns on the crowdfunding platforms and search for manufacturers mainly in China for the product ideas displayed in crowdfunding campaigns and reach the target market swiftly. An air conditioning controller raised over one million dollars for $129 each whereas copycats of this product are popular on Alibaba for only around $20 each. A common practice to prevent a product idea is to patent it before revealing it widely to the mass. Just patenting a product is not enough to protect a product. For example, ‘Ove’ Glove patented itself. However, it faces a severe challenge to monetize the idea due to numerous copycats available on Amazon and other Chinese e-commerce websites at a significantly lower price. Removing fake product sellers from e-commerce platforms takes several months. Furthermore, if a fake product seller is removed from an online site, s/he can resurface with a different brand name. Another option to protect a patent is to go to court but it may take several years with high costs to settle the case. It is not practical to go court for start-ups due to their resource and time constraints. Table 1 shows a list of crowdfunded products that are copycatted and sold at a significantly lower price.

Table 1. Some crowdfunded products that are copycatted in China

Israeli entrepreneur Yekutiel Sherman’s yearlong battle with China’s copycats reveals how hard it is to protect ideas. His smartphone case with a built-in selfie stick featured on crowdfunding platform Kickstarter was copied by Chinese fraudsters and the copycats are available in the market ahead of months before his intended release date. The price of the selfie stick on the Kickstarter campaign was $19 while similar selfie sticks are available across eBay, Amazon, Taobao, AliExPress, and numerous other e-commerce websites at around $8. Some of them are even using the name of Sherman’s product—Stikbox. Yekutiel Sherman raised $4700 from 929 backers who have requested a refund of their pledge and many of them were buying copycats from different online e-commerce platforms. FinalStraw is a reusable and foldable straw to reduce plastic waste. It raised around $1.9 million on Kickstarter. Soon after raising the fund, FinalStraw is fighting Chinese copycats that are priced a fraction of the FinalStraw price. FinalStraw is priced at $25 but copycats are available at $5. Social media influencers are used to market copycat straws, too. A company came up with a device called Pressy that can plug into the headphone jack of smartphones and provide signals to the phone with the press of a button. It started a crowdfunding campaign on Kickstarter and soon discovered that a Chinese website is using their product images in a crowdfunding campaign. The products of the Chinese company are identical copies of the Pressy. Guess what, the Chinese company managed to reach its crowdfunding goal beating the original inventors. More surprising is that Chinese mobile phone company Xiaomi used a Pressy-like button for their phones using the same factory that was earmarked for the production of Pressy. Suing a giant like Xiaomi was impossible for a small start-up, Pressy.

Chinese entrepreneurs take several approaches to benefit from someone else’s inventions. They can come up with copycats long before the original products reach the target market. When manufacturing for original entrepreneurs, manufacturers may produce extra units of a product and sell to another company or sell themselves online at a lower cost. Even the Chinese manufacturers that produce products for the Western start-ups may not breach the agreement but there are many other factory owners who see the products at the time of manufacturing and they can produce the same products with a different brand name. It is impossible to sue all these people and money to be spent to sue so many people is not practical.

Intellectual property works differently in China, compared to Western countries. For example, the first-to-use system is used in the USA while the first-to-file system in China. That means whoever applies for the intellectual property rights first would receive the right irrespective of who came up with the invention. An invention from outside China is banned in the Chinese market if someone already received intellectual property rights.

Copycats are beneficial for Chinses companies who start with tweaking Western products and learn how to develop or innovate something better at a lower cost. If we only blame the Chinese companies for copycats, we will miss the discourse of many talented Chinese start-ups who successfully raised funding through Western crowdfunding platforms. However, copycat tag is harming the Chinese innovative start-ups. A recent report pointed out that 39 Chinese entrepreneurs raised over one million dollars on the crowdfunding platform Indiegogo by 2019. Most of these entrepreneurs developed products for Western customers. For instance, a Chinese entrepreneur Jacob Guo wanted to launch his campaign for his skateboard but he was worried that backers may think his skateboard is fake and hence would not fund it. To deemphasize the Chinese origin of the product, his team preferred to avoid mentioning the origin of the product. Some Chinese entrepreneurs use Western actors as a spokesperson or campaign using Western lower level members of the team to deemphasize the Chinese origin. Reports suggest that when even the target audience is Chinese customers, the Chinese start-ups have a prejudice against Chinese products. Moreover, Chinese entrepreneurs use Western models to garner an image of high quality and reliability, and that gives an opportunity to set a higher price bracket for a product. Western entrepreneurs can take some initiatives to mitigate copycats of the crowdfunding products as pointed out in the next section.

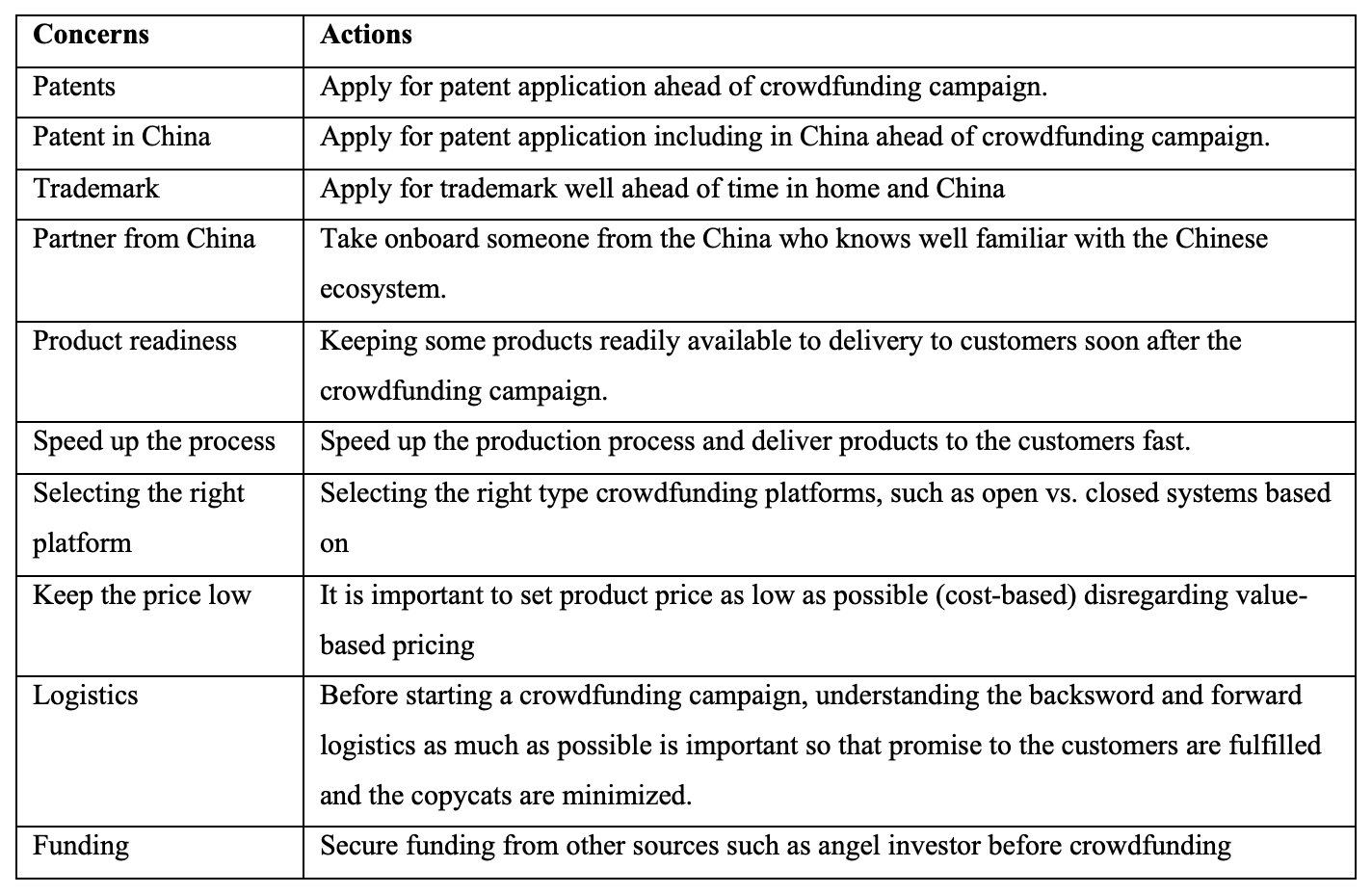

A recent study suggests that start-ups, before going for crowdfunding campaigns, may consider legal protection, ease of imitation and ability to take the business ideas to markets fast (Cowden and Young, 2020). Western startups always need to keep in mind that someone in China is going to copycat their products before they start producing their products. Table 2 provides the main concerns and actions start-ups can take to prevent copycats. Intellectual property protection, inimitability, speed to market, and selecting the right crowdfunding platform are important to consider before launching crowdfunding campaigns. Start-ups can try to protect their ideas in a number of ways. They can patent their products before launching crowdfunding campaigns. Similarly, they can apply for a trademark much ahead of the campaigns. Start-ups should consider that receiving patent and trademark take many months to years. They should also consider gaining patents in China, which is the main source of copycats. Moreover, it is advisable to register for trademark protection in China, as it is the main threat for copycats and bring on board someone from China, who is well familiar with the Chinese innovation ecosystem. Speeding up the process is imperative, keeping the copycat concern in mind throughout the crowdfunding process.

Table 2. Concerns and actions start-ups can take to prevent copycat

A product that includes mechanical, electrical and software components is harder to copy by others. One way to defend products from copying is by integrating software into their hardware. Start-ups need to consider backward and forward logistics well ahead of the crowdfunding campaign so that, if successful, they can quickly deliver the products to the customers. Filing provisional patent applications in the home country (e.g., USA) and the country of copycat (e.g., China) before going for crowdfunding campaigns may be crucial so that they can defend their intellectual property in court. Gaining trademarks as early as possible is important as it may take many months to receive an approval in the USA, for example. It is wise to keep the price low in the crowdfunding campaigns so that copycats will have difficulty to sell at a lower price. Start-ups may think of having products readability available so that they can dispatch the products to the customers soon after the crowdfunding campaigns. Since China is the main source of copycats, it might be useful to bring in someone from China onboard, especially someone who is well connected with the manufacturing hubs in China. Another approach is to raise venture capital or secure angel investors before crowdfunding so that experienced people are already onboard. Despite all due diligence and measures, protecting crowdfunding ideas from copycatting will remain a challenge.

Cowden, B. J., & Young, S. L. (2020). The copycat conundrum: The double-edged sword of crowdfunding. Business Horizons, 63(4), 541-551.

Hossain, M., & Creek, S. A. Unveiling and Brightening the Dark Side of Crowdfunding. California Management Revie, https://cmr.berkeley.edu/2021/09/unveiling-and-brightening-the-dark-side-of-crowdfunding/

Mollick, E. (2014). The dynamics of crowdfunding: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(1), 1-16.