California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier academic management journal published at UC Berkeley

by Jonathan Hughes and Ashley Hetrick

Image Credit | Alex Kotliarskyi

A well-known wisecrack describes the matrix as “an organizational design where everyone can say ‘no’ and no one can say ‘yes.’” Based on the findings of our multi-year study of organizational effectiveness, that joke succinctly captures daily life at many companies.

“Implementing Design Thinking: Understanding Organizational Conditions” by Cara Wrigley, Erez Nusem, & Karla Straker

“Integrating Design into Organizations: The Coevolution of Design Capabilities” by Tua Björklund, Hanna Maula, Sarah A. Soule, & Jesse Maula

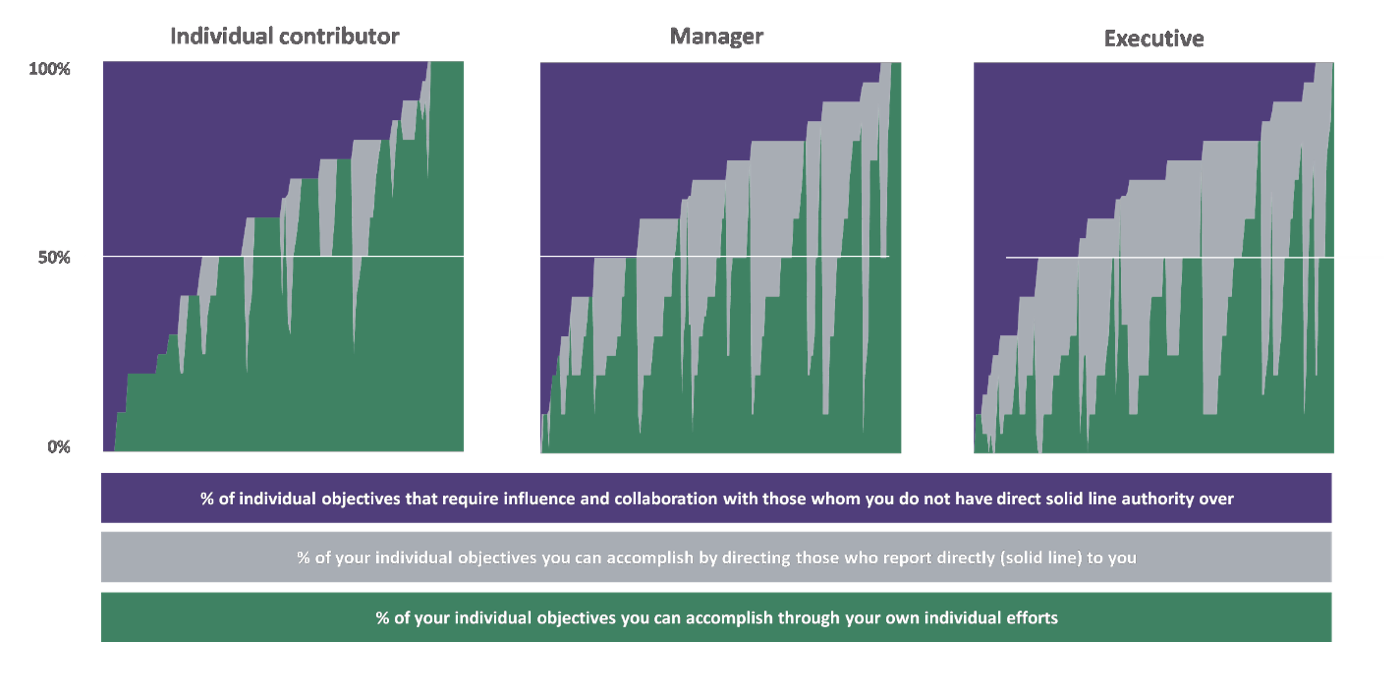

The matrix emerged in the 1970s and proliferated as an alternative to traditional organizations with more clear-cut hierarchies and dedicated teams. In a typical matrix structure, people report to multiple managers and often need to work closely with people across other functions and business units. They are also, as the chart below illustrates, highly dependent on the cooperation and support of others to meet their own objectives.

Thanks to the complexity and ambiguity inherent in this organizational model, feeling “lost in the matrix” is commonplace among employees and leaders at many companies. Organizational performance is often lost in the matrix as well. Diverse perspectives create conflict rather than innovation. Decision-making gridlock undermines agility and compromises execution.

Our study of organizational effectiveness, originally conducted from 2013 to 2018 and updated over the past three years, encompasses more than 750 survey responses from individuals representing more than 500 companies, plus interviews and case-study analysis. We found that in many—but not all—matrixed organizations, complexity impedes both the speed and the quality of decision-making and execution. Not only does the complexity inherent in matrixed organizations make it harder to execute day-to-day operational tasks, it also impedes strategic agility and innovation. Indeed, 43% of respondents from highly matrixed companies report “organizational complexity impedes the quality and speed of decision-making and innovation ‘some’ or a ‘great deal.’”

Nonetheless, the matrix is the predominant organizational design not just for multi-billion-dollar companies, but for organizations of all sizes. In our study, a mere 10% of respondents stated that their organization was “not matrixed.” Of the remaining 90%:

Complexity in the matrix can become a grinder that undermines morale, damages relationships, and makes execution of even routine tasks unnecessarily difficult and inefficient. Only 15 percent of respondents from highly matrixed organizations report that roles and responsibilities in their organizations are “completely clear.” Our study found that:

Only 11% of our study respondents from highly matrixed organizations report that objectives and incentives of different business units and functional areas in their company are “completely aligned.” 48% of all study participants report that objectives and incentives are only “somewhat aligned” or “not at all aligned” across business units and functions. Some jostle and contention among different business units and functions is to be expected. Specialization of labor means that goals and priorities will never really be perfectly aligned. But the more goals and incentives diverge, the more decision-making, effective collaboration, and timely execution are put at risk.

Indeed, most participants in our study report that differences are a significant source of conflict and inefficiency at their organizations. Disruptive and damaging conflict proliferates when different individuals, departments, business units, and leaders have significantly different objectives. In the absence of clear lines of authority, and without the ability to effectively collaborate to harness differences to their advantage, organizations struggle to make decisions efficiently and execute effectively.

Intent on breaking this gridlock, many organizations have invested in training on skills for influence. The logic goes something like this: In the absence of clear hierarchy and decision-making authority, people need better influence skills to get decisions made and then work together to implement them. Indeed, 87% of individuals in companies where objectives and incentives are not aligned rate the ability of individuals in their company to influence others as “poor” or only “moderate.”

All too often, however, such training is focused on helping people to be more “persuasive” and better at getting others to agree with them. This does little to break the cycle of conflict that arises as people with different goals, and different ideas about how to achieve them, seek to operate effectively within matrixed organizations. When people think influence is about getting others to agree, giving them better skills to do so does little to enable them to leverage differences for better decision-making, for learning, and for innovation. Instead, the result is a sort of influence arms race where everyone is equipped with better skills for convincing each other that “My view is right” and “You should subordinate your priorities to mine.”

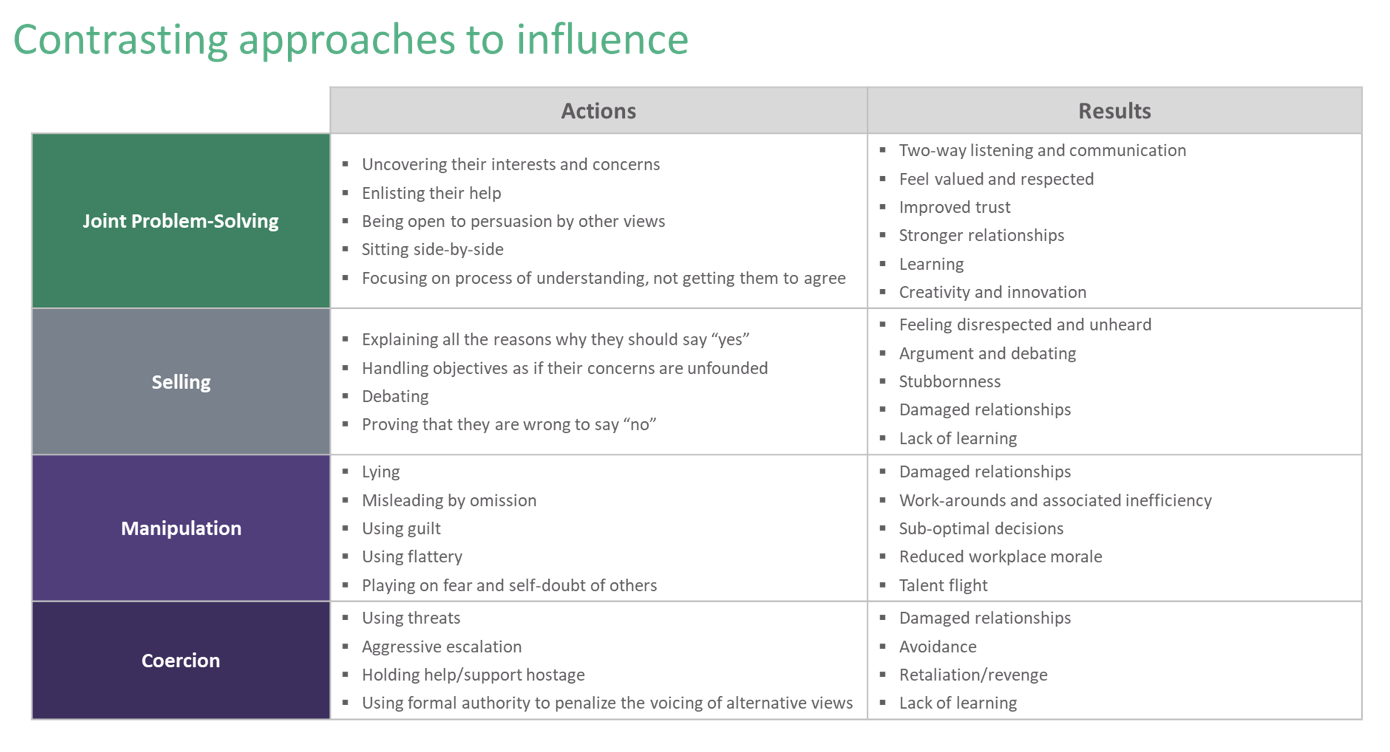

As the matrix replaced traditional hierarchy and eroded command-and-control management, the need for influence did indeed increase. Based on our research, and over twenty-five years of consulting to organizations around the world, we have identified an influence spectrum spanning four distinct modes of influence: coercion, manipulation, selling, and joint problem-solving. (See chart, “Contrasting approaches to influence,” which describes typical actions and outcomes of these behaviors.)

Our study asked individuals which of these modes “best characterizes the most common approach taken by people in your company when they need to influence others?” 35% cite joint problem-solving — the optimal approach to influence. Unfortunately, two-thirds of study participants report that sub-optimal influence approaches prevail in their companies. Our study also reveals the shocking pervasiveness of manipulation and coercive influence tactics — reported by one in four study participants as the most common approach to influence in their organization!

38% of our study participants respond that the dominant influence mode at their company is “selling” — trying to convince others why your idea is best and/or how it will benefit others to agree with you or provide support. Selling is not toxic in the way manipulation or coercion is, but neither is selling a benign behavior in the matrix. Selling — with its bottom-line goal of getting others to agree — does nothing to enable the productive integration of different perspectives and priorities. When selling behavior predominates at scale across an organization, it produces (at best) sub-optimal compromise. At its worst, selling spawns conflict, stalemate, and gridlock.

What’s the alternative to a “persuasion arms race”? A new paradigm for influence — one built not on extracting agreement from others, but on embracing differences while engaging on joint problem-solving.

Differences are a fact of life, and disagreement is inevitable. For example, functional groups such as Marketing, Sales, Finance, and Procurement necessarily have very different goals, priorities, and perspectives. Those differences are a feature, not a bug, of organizational design. But trouble arises when multiple functions are unable to balance competing objectives and synthesize conflicting points of view to advance the goals and success of the enterprise as a whole.

Only 9% of our study’s respondents report their company views differences (e.g., different goals, strategies, competencies, perspectives, and styles) as a significant source of learning and innovation. Instead, differences — specifically, the inability to embrace and reconcile them — represent an enormous challenge for most companies, their leaders, and employees at all levels.

The solution is a fundamental re-conception of influence as a two-way street. When differences arise and disagreement occurs, we need to think of influence not as a matter of seeking agreement from others, but rather seeking it with them. We need to focus not only on being persuasive, but also on being open to persuasion. Put another way, we need to re-conceive influence as a way of working together, without reliance on or recourse to hierarchy, where we seek a better solution than either of us could create alone. Being open rather than defensive when others disagree — embracing and leveraging differences — unlocks learning and innovation.

According to our research, organizations where people report that differences are a significant source of learning and innovation are:

Far from lost in the matrix, people at these organizations have the skills to collaborate amidst differences, and to transform those differences from a liability to an asset. They possess the ability to make decisions quickly and execute with efficiency, and to engage in continuous learning and innovation. They collectively create an organizational culture where the matrix’s pervasive “No” and “I can’t” is replaced with constant exploration of “What if we..?” and a commitment to find a way to “Yes.”