California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier academic management journal published at UC Berkeley

by Daniel J. Finkenstadt, Rob Handfield, and Tojin Thomas Eapen

Image Credit | Mika Baumeister

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 we have continued to see massive disruptions to our global supply chains, which has led to hoarding behavior in consumer and industrial markets. Initially it started with irrational hoarding of supplies like toilet paper, but also led to a “pile-on” effect) as disruptions to PPE supply prompted healthcare providers and distributors to place orders with anyone and everyone! As people realized that 90% of healthcare “medsurge” supplies were produced in Asia, COVID set off a mad scramble by all countries, states, and organizations to obtain the necessary personal protective equipment (PPE) to stay open, many with varied levels of insight into available stock levels (Finkenstadt and Handfield, 2021). For instance, a large mask manufacturer we spoke with discussed how their monthly demand for N95 masks went from 2 million per month, to more than 1 billion for several months in a row! Irrational demand can also lead to sharp drop-offs in future demand as stockpiles grow and uncertainty is assuaged. This can lead to companies having to reduce supply capability, impacting supply further downstream.

“The Impact of COVID on Current and Future Business Operations” by by Vijaya A. Bansode

Researchers have found a plethora of likely contributing factors to irrational demand behavior such as social media and social cognitive biases, pandemic stress, fear of contagion, and particular personality traits (conscientiousness). (Labad et al., 2021). The current set of supply chain disruptions has led to a massive set of supply chain shortages while e-commerce and sponsored advertisement has grown (Bansode, 2021). There has been a disconnect in the ability for free market price levels to satiate demand. A new level of agility is required by firms to deal with the sudden shortfalls in supply to meet this demand. We propose certainty satiation marketing. This involves using transparency of supply for demand moderation to create a satiation effect. It is focused primarily on managing the information and advice available to consumers so that they can reach satiation at the appropriate time, given environmental market conditions.

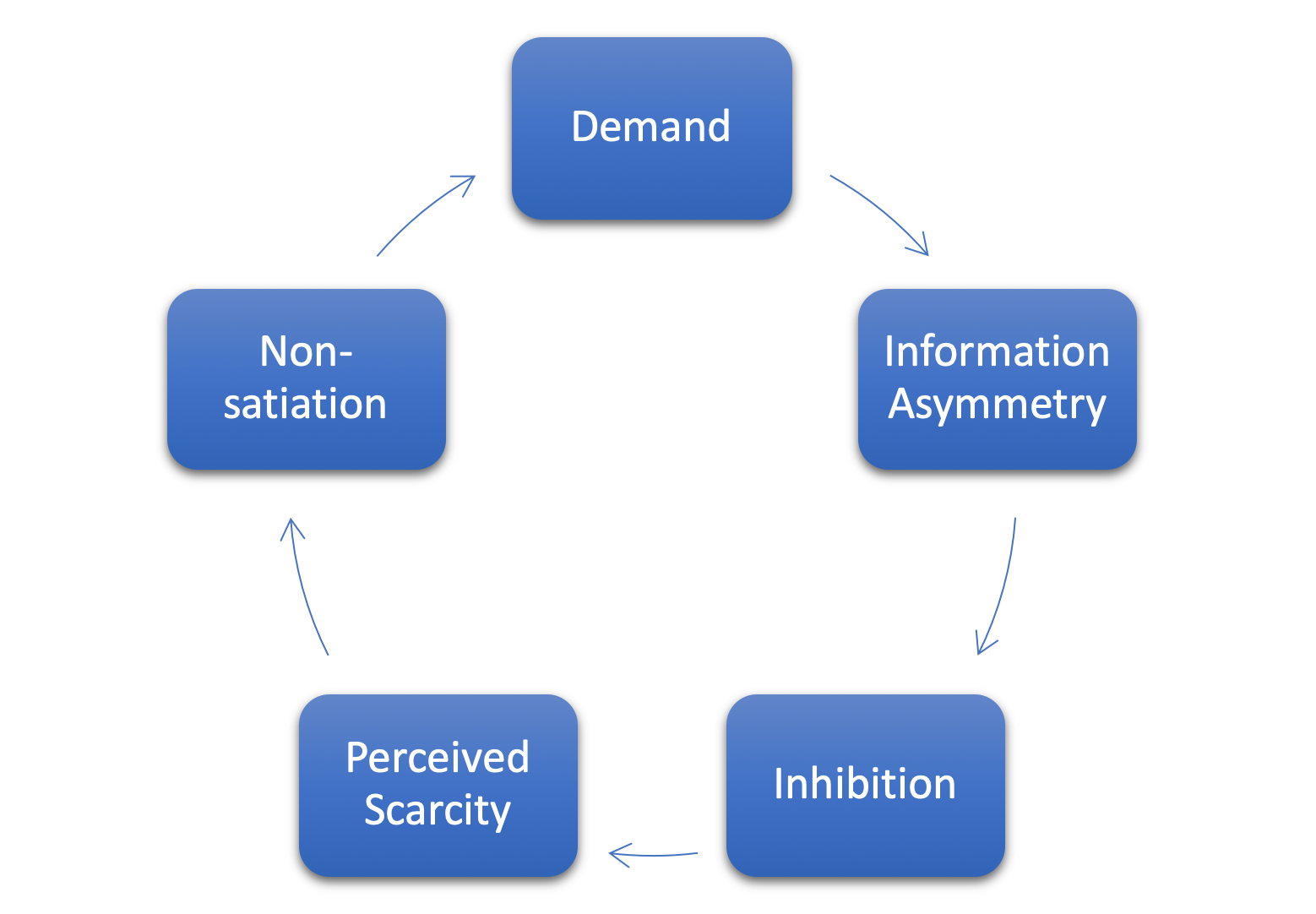

Demand management has been handled in various ways. Natural price increases should manage demand, but we have seen that price increases can reach a point of hyperinflation. Rationing is another demand management strategy, but it has its downsides as well. Buyers and sellers develop strategies for consumption and production based on asymmetric information. Over time the market is supposed to reach a rational equilibrium. But major disruptions to markets for products that become global commons such as PPE, fuel, toilet paper etc. can lead to irrational buying and selling behaviors. Standard approaches used to inhibit irrational/unreasonable demand such as product rationing and tiered pricing are likely to lead to perception of scarcity, which in turn leaves customers unsatiated. This lack of satiation further drives up demand, aggravates the supply chain and creating a vicious demand satiation uncertainty loop (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Demand Satiation Uncertainty Loop

Unsatiated demand can lead to aggregate reactions such as stock-piling and black markets. In 2020 we saw everything from erratic toilet paper hoarding to consumers filling trash bags with fuel when domestic petroleum supplies were put at risk by weather and cyberattacks. In these cases, it would have been beneficial to manage demand with a concerted marketing strategy that sought to reduce asymmetric information and increase market certainty until things returned to normal.

Consumers continue to order, and manufacturers continue to ship, but the global system is not prepared to logistically process a flow of irrational buying-selling behaviors brought on by the chaos of a pandemic. Currently there are thousands of empty containers piling up in the port of Los Angeles and hundreds of container ships waiting days if not weeks to unload their cargo, further delaying deliveries and growing public sentiment that the supply chain cannot meet their demands. Most of this is impacting imports from Asia, primarily China. As such, organizations who rely on Chinese imports should consider alternative approaches as demand will unlikely be met.

Satiation in economics can be defined as the point at which additional consumption beyond such a point would yield diminishing marginal utility relative to the cost to consume it. In the marketing literature, satiation is defined as “the process whereby consumers enjoy a stimulus less as they consume more of it” (Coombs and Avrunin 1977; Redden 2008; Sevilla and Reddin, 2014, p. 206). In general, most marketers would favor conditions where consumers avoid reaching a point of satiation and prefer continuous consumption to provide a stream of revenue and on-going profit maximization. Marketing research also suggests that people reach this satiation point as they consume additional quantities of an item or service and, once the satiation point is reached, they move on to consume other types of products or services (Coombs and Avrunin, 1977; Herrnstein and Prelic, 1991). Traditional marketing strategies tend to dissuade satiation for this reason.

We suggest that these are not the optimal long-run paths for marketers, supply chain managers, firms, and governments to follow. Rather, both private and public sector organizations have a social responsibility to employ transparent and factual messaging, to create a new level of satiation for consumer certainty that may help to reduce strains on a global system of goods and services by increasing awareness of resource constraints. When information is sparce, trust may wane. A lack of trust in the system can lead to inefficient market behaviors by self-interested parties. This is consistent with the emerging view of a ‘commons’ during times of mass contingency and global healthcare disruption that became obvious during COVID-19. Our research suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic has created many new forms of supply chain commons for many public health goods and services, which suffered from a lack of transparency and equitability to achieve a desired point of stabilization (Handfield et al., 2020; Finkenstadt et al., 2021). Certainty satiation marketing and supply chain commons planning can serve as a form of market demand management during a period of extreme supply chain disruption.

Currently we are seeing massive disruptions in almost every industrial and commodities sector. In recent conversation a CPO of a major CPG company shared how she was in the process of “educating” her Chief Marketing Officer on how raw material prices could not be made up through productivity, and that the only way to continue operating a profitable business was to pass on these price increases to consumers. Many companies have publicly announced they anticipate these shortages to continue well beyond 2022. There is increasing evidence that companies need to educate consumers of the reality of what is happening in global supply chains, that is leading to longer lead times, increased pricing, and reduced product availability in retail and e-commerce channels. The irony of this point cannot be missed: we need to inform a broad consumer base that their commercial buying behaviors, resulting in a demand surge, are part of the reason for global supply chain disruptions!

In the past governments have tried to deal with these supply chain problems via social marketing. Public Service Announcements (PSAs) have been around in America since World War II as a form of social marketing. Social marketing is defined as “process that applies marketing principles and

techniques to create, communicate and deliver value in order to influence target audience behaviors that benefit society (public health, safety, the environment, and communities) as well as the target audience” (Kotler, Lee and Rothschild, 2006 personal communication cited in Cheng, Kotler and Lee, 2009). Researchers have cited the use of social marketing for health promotion, injury prevention, environmental protection, and community mobilization (Kotler and Lee, 2008). One downside of this method has historically been the development of black markets. Black markets increase the risk of counterfeiting and we have seen that behavior occur in dangerous and unregulated ways for items like N95 masks, vaccines, and vaccine cards during COVID19.

We suggest that governments and firms consider focusing on a new area of marketing, certainty satiation marketing, as an alternative to traditional inhibiting forms of demand management such as social marketing, demand-based pricing and rationing. We are NOT suggesting that we always tell customers to STOP consuming, as is done in social marketing (i.e., reducing coal or petroleum fuel consumption that can negatively impact production levels). Instead, we are asking them to consider the impact on global commons (i.e., for the common good of humanity and the community) and utilize commons-focused communications about the market.

The social benefit in this case is related to the need to ease constraints facing global supply chain operations. Supply chains are pivotal, as we have seen, to the flow of everything from food markets to defense markets, and shortages can create havoc in healthcare, air travel, transportation, and even a trip to the supermarket. The imbalances currently facing supply chains is having major impacts on public health and welfare but is even disrupting parts delivery for harvesting equipment for farmers, putting the 2021 fall harvest at risk when equipment cannot be maintained in a functioning state. But satiation marketing is also about clearly articulating the availability and shortages of goods to consumers which can reduce uncertainty, build trust, and improve cooperative market behaviors. This is not about stating how much or how little consumers should buy, but rather involves direct and indirect influencing of consumers to only buy what they need, and not to hoard at the expense of others in their own communities.

This line of thinking may turn the marketer’s job a bit on its head. Instead of focusing on delaying satiation by manipulating perceived scarcities for the purpose of continuous demand and revenues, the strategy involves increasing supply chain transparency and equitability for the purposes of reaching rational satiation levels commensurate with market realities. In a sense, creating alignment between demand and supply constraints is a means of informing consumer expectations, which will in most cases lead to measures of conservation.

There is also risk that by not partaking in certainty satiation marketing, entities may choose to enact demand management strategies that seem helpful but are actually harmful. Instead of rationing the good they may simply ration information. This can also lead to poor outcomes. For example, recently a non-profit PPE provider told us that they were unable to advertise domestically produced N95 masks on Google because Google had stated that the US government was asking them to not advertise N95s anymore due to supply shortages. However, the non-profit informed us that this supply shortage was only for traditional name brand products like 3M, not for newer domestic products. In effect Google was rationing advertising information. Google was unaware that there were a host of domestic respirator firms who were stood up using government funding in 2020 and were at risk for bankruptcy because they could not overcome the competition from cheap Asian products. Subsequently, these domestic manufacturers couldn’t get their advertising posted to take advantage of the market when those competitors were low on stock. If Google and the government were working to develop stronger certainty satiation marketing strategies, they could, instead, increase transparency into the types of products that were available for advertising (i.e., domestic respirators) and only advertise the traditional name brand (i.e., 3M) products once the available supply reached a predetermined level of stock that could meet demand. By rationing the information on available stock, Google had inadvertently contributed to the feeling of resource uncertainty, reduced the chances for onshore supply sustainability and left consumers in the dark.

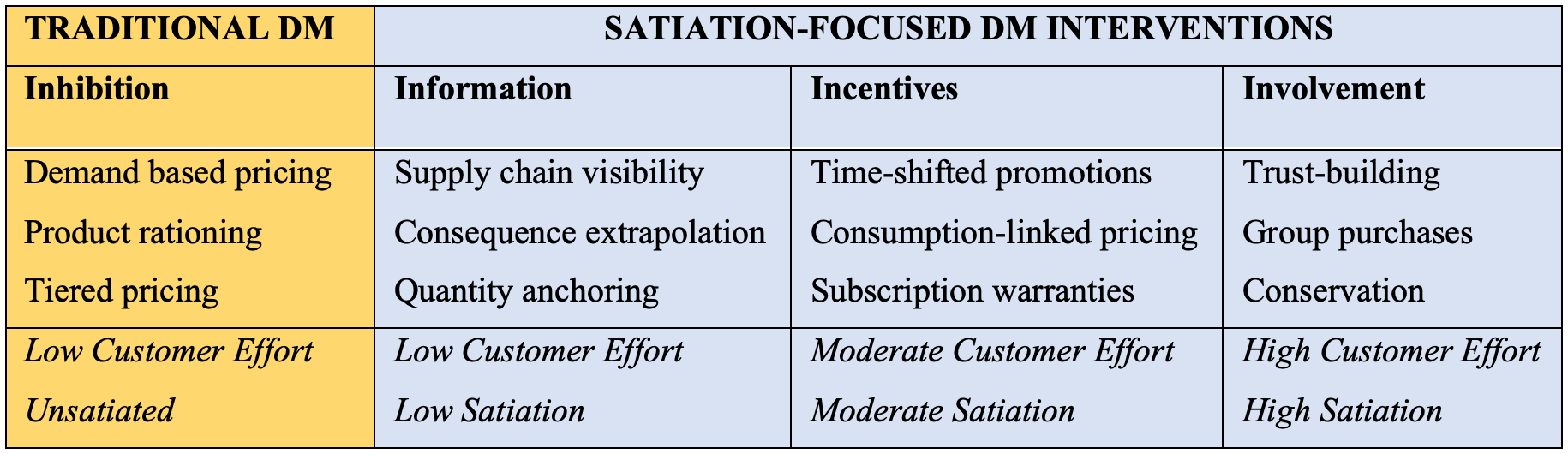

As an alternative, we propose a softer approach to demand management which involves designing interventions to satiate (not inhibit) demand. As discussed above, irrational/unreasonable demand is driven by asymmetry of information, misaligned individual incentives,1 and lack of trust. Thus, effective strategies can emerge from increased transparency of company information, aligning individual incentives to desired global outcomes, and encouraging broader customer involvement in the supply-chain process. A company or agency might start with information-based strategies, and then move to incentives, and then involvement. In the table below we provide a list of potential interventions that can be used to satiate demand using information, incentives, and involvement as drivers.2 Demand based pricing is not always a reliable control for demand when health is uncertain. Healthcare services have been historically inelastic (Ringel et al., 2002). During the first year of the pandemic healthcare products, such as PPE, became the same with prices soaring at times to 1,000%-2,000% for many items (Berklan, 2020). Rationing has been shown to lead to black markets for goods and services or strategic buying behaviors. During the early stages of the pandemic retailers were capping the amount of toilet paper each person could buy but customers were getting around this by having others who had already hoarded their stock buy for them or by making multiple store visits. And tiered pricing, where a consumer pays a higher per-unit price beyond a threshold quantity, is quickly rendered ineffective if consumers make multiple store-visits to purchase products at a lower price or when products are purchased by individuals hoping to profit from arbitrage. More importantly, these strategies drive a perception of scarcity, further fueling demand.

Satiation focused strategies leverage information to build trust and should be considered in the future. Simply providing further visibility into supply chains reduces uncertainty surrounding future availability of goods and services and can help to rationally balance demand. Of course, this assumes that suppliers and manufacturers have this visibility themselves. Social proof and quantity anchoring can be used to give a clearer picture of others consumption rates, thereby influencing consumer’s reference points for rational consumption in uncertain climates. Like social marketing, consequence extrapolation can be tailored to provide information about consumer demand and potential choices on the health and well-being of others. For example, COVID-19 vaccine booster shots are currently an ethical dilemma when half the world has not received their first shot. Yet human behavior in this uncertain time has caused many to seek their booster shots illicitly, impacting the global commons (Gutman, 2021). How might they behave if they knew the actual impact of jumping the line?

Incentive alignment tends to go hand-in-hand with supply chain visibility and has been shown to improve outcomes for all parties (Narayanan and Raman, 2004). Providing additional information lends itself to the ability to better align incentives. Suppliers could use methods that align price savings features of a product to its actual usage versus simply a promotional period. At the same time suppliers and retailers can look to supply-based promotions as a way of moving excess stock of substitution products. For example, in the case of N95 masks, producers could offer better pricing for domestic product during a time when traditional, cheaper suppliers are short of supply, and advertising platforms like Google can help highlight them during such a period and thus increase the overall benefit to the greater commons supply chain and consumer. In a similar manner time-shifted promotions can have similar effects by providing discounts into a future period when normal consumption would be assumed to have taken place. Price promotion need not be the only mechanism shifted to rebalance demand.

Buy-now deliver later (BNDL) and subscription warranties provides a mechanism for reducing future availability uncertainty by allowing consumers to preorder items and simply wait on them to arrive at a called upon date in terms of BNDL or a specified delivery schedule in terms of subscription warranties. This creates a means of delaying delivery until a normal, more rational, consumption period expires. However, both methods require a great degree of trust on the part of the consumer that firms and governments can support through strong enforcement governance and supply chain transparency.

Building trust may not occur in the chaos of a pandemic or other mass calamity without getting the consumers, firms and governments involved in collaborative activities that build on information transparency and incentive-alignment. Google Trends shows that from Oct 2019 to Nov 2021 searches for supply chain “shortage”, “crisis”, and “management” are up 900%, 500% and 250% respectively. The public is aware there is a problem, and they are more curious than ever in recent history. It is an exceptionally opportune time to use trust-building engagements with the public to discuss efficient, resilient, and ethical supply chain management and consumer demand behavior during times of global crises. This can be used to encourage actions as simple as group purchasing with capped quantities at lower prices, to engaging in crowdsourcing solutions to supply and demand issues plaguing these new market commons in a post-pandemic world.

Table 1: Comparison of Example Demand Management (DM) Strategies

We can’t solve all the supply chain woes of the past two years with these ideas. But we can suggest exploration into a new form of research, public policy, and business practice focusing on illuminating supply chain conditions for the purposes of reaching a rationale point of consumer demand during global disruptions. We simply implore the world to look for greater information symmetry, trust, incentive-alignment, and stakeholder collaboration in an effort to help curb moments of unsatiable, irrational, and collectively harmful demand. We need to eliminate the demand satiation uncertainty loop that has haunted us these past two years and get our supply chains back on track. We believe that certainty satiation marketing can help and should become a standard strategy for firms and agencies in the post-pandemic world.

*The opinions and ideas stated in this work are those solely of the authors and do not represent the official positions of the Department of Defense, its services, or the federal government.

1. Bansode, V.A. (2021). “The Impact of COVID on Current and Future Business Operations”. California Management Review Insights. https://cmr.berkeley.edu/2021/03/the-impact-of-covid-on-current-and-future-business-operations/

2. Berklan, J.M. (2020). “Analysis: PPE costs increase over 1,000% during COVID-19 crisis” Retrieved 8 November 2021 from: https://www.mcknights.com/news/analysis-ppe-costs-increase-over-1000-during-covid-19-crisis/

3. Cheng, H., Kotler, P. and Lee, N.R. (2009) Social Marketing for Public Health, Chapter 1. pp. 1-30

4. Coombs, Clyde H. and George S. Avrunin (1977), “Single-Peaked Functions and the Theory of Preference,” Psychological Review, 84 (2), 216–30.

5. Finkenstadt, D.J. and Handfield R. (2021). Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 27 (2021). Blurry vision: Supply chain visibility for personal protective equipment during COVID-19. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 27(3).

6. Gutman R. (2021). Booster Bandits Are Walking a Fine Line: Getting an illicit third shot has gone mainstream, but it’s still a real ethical dilemma. The Atlantic. Retrieved 8 November 2021 from: https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2021/09/booster-bandits-ethics/620048/

7. Handfield R, Finkenstadt DJ, Schneller ES, Godfrey AB, Guinto P. A Commons for a Supply Chain in the Post‐COVID‐19 Era: The Case for a Reformed Strategic National Stockpile. Milbank Quarterly. 2020;98(4):1058-1090. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12485

8. Herrnstein, Richard J. and Drazen Prelec (1991), “Melioration: A Theory of Distributed Choice,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5 (3), 137–56.

9. Kotler, P. and Lee, N.R. (2008). Social marketing: Influencing behaviors for good (3rd ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications

10. Labad, J., González-Rodríguez, A., Cobo, J., Puntí, J., & Farré, J. M. (2021). A systematic review and realist synthesis on toilet paper hoarding: COVID or not COVID, that is the question. PeerJ, 9, e10771. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.10771

11. Narayanan V.G. and Raman, A. (2004). Aligning Incentives in Supply Chains. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2004/11/aligning-incentives-in-supply-chains

12. Sevilla J, Redden JP. Limited Availability Reduces the Rate of Satiation. Journal of Marketing Research. 2014;51(2):205-217. doi:10.1509/jmr.12.0090

13. Redden, Joseph P. (2008), “Reducing Satiation: The Role of Categorization Level,” Journal of Consumer Research, 34 (5), 624–34.

14. Ringel, Jeanne S., Susan D. Hosek, Ben A. Vollaard, and Sergej Mahnovski, The Elasticity of Demand for Health Care: A Review of the Literature and Its Application to the Military Health System, Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, MR-1355-OSD, 2002. As of November 01, 2021: https://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1355.html

Individual’s short terms incentives are misaligned with the broader welfare of society, as well as potentially the individual’s own long-term interests.

Can the three classes of strategies be represented on two dimensions (effort v impact). Information is low effort low impact, incentives are moderate effort moderate impact, and involvement is high effort high impact.