California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier academic management journal published at UC Berkeley

by Aideen O'Dochartaigh

Image Credit | Brendan O'Donnell

After decades of voluntary engagement when sustainability disclosure has failed to translate to substantive performance,1 Environmental, Social & Governance (ESG) reporting is on the cusp of a regulation revolution, with landmark legislation proposed in economically significant jurisdictions including the European Union (EU) and U.S. With new frameworks come new accounting, governance and cost challenges for managers. What do firms need to do right now to prepare for the regulation revolution?

“The Practitioner’s Perspective on Non-Financial Reporting” by Francesco Perrini. (Vol. 48/2) 2006.

ESG regulation is not new; the Carrots & Sticks project chronicles the diverse array of discrete legislation globally.2 But the scope and implications of the EU and U.S. proposals are significant. Firms not just listed in, but with substantial activity in the U.S. and EU, will be subject to the new regulations.

As part of its Green New Deal programme for a low-carbon economy, the EU is finalizing the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). The legislation, which will require over 50,000 firms to report independently verified ESG indicators, is accompanied by the EU Taxonomy, under which companies must disclose the percentage of their activity which contributes to environmental objectives.

In the U.S., the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is also finalizing its Mandatory Climate Risk Disclosures legislation, requiring SEC registrants, about 6,600 companies including foreign private issuers, to disclose climate-related information in annual filings.

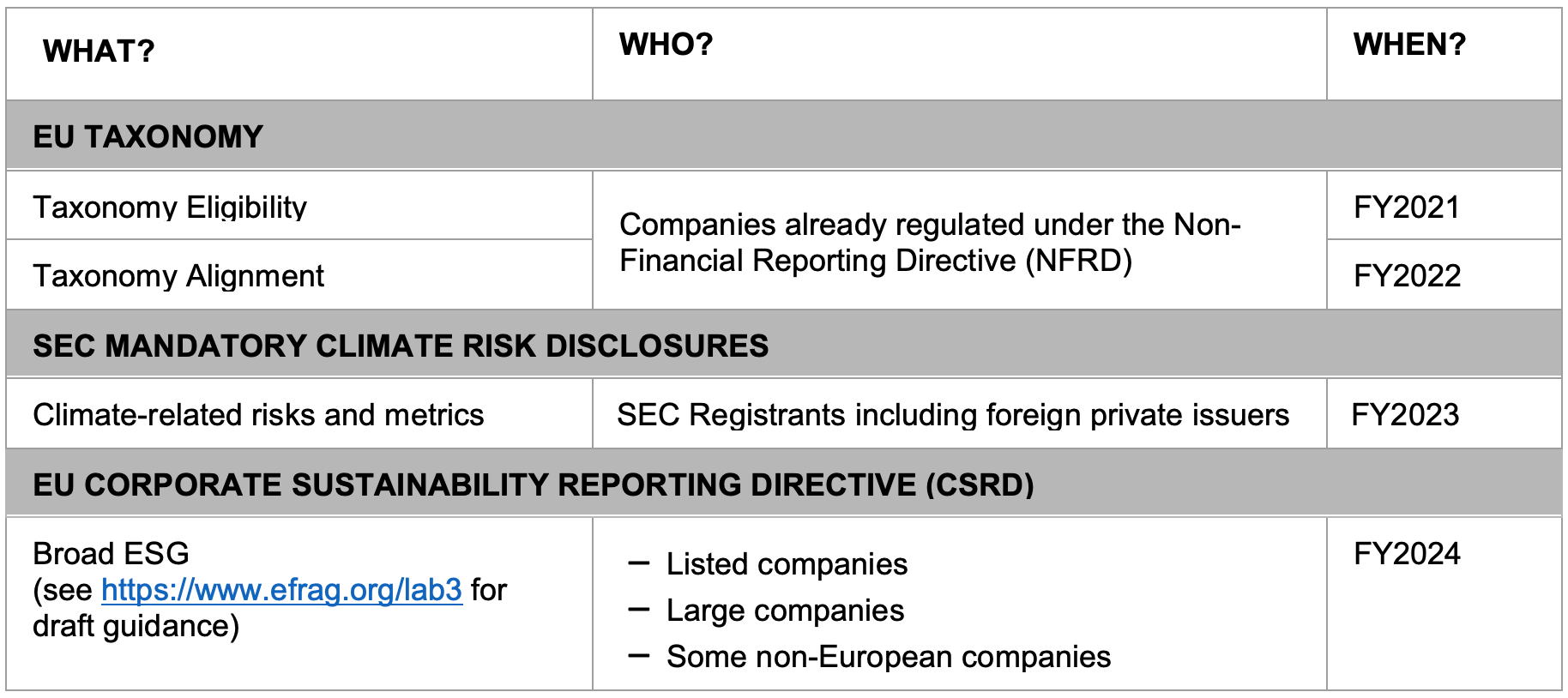

Key deadlines and timelines are outlined below order of immediacy. EU Taxonomy reporting requirements have already taken affect for some companies and the CSRD will likely begin to apply in FY2024.3 SEC Climate Risk disclosure is currently set to apply from FY2023.

Table 1: Forthcoming ESG Disclosure Regulation: What, Who, When?

The EU Taxonomy is designed to drive sustainable investment, indicating whether a firm’s activities align with environmental objectives. Firms must report on Taxonomy eligibility and Taxonomy alignment.

Taxonomy eligibility: The firm must disclose what percentage of its turnover, operating expenditure and capital expenditure is taxonomy eligible, meaning it must contribute to at least one of six environmental objectives. For firms already subject to the NFRD, they must report on Taxonomy eligibility for two objectives - climate change mitigation and adaptation - for FY2021 onwards. This will be extended in FY2022 to the other objectives, including biodiversity, circular economy, protection of water and marine resources, and pollution prevention.

Taxonomy alignment: Reporting on Taxonomy alignment will be required for FY2022 for non-financial undertakings and FY2023 for financial undertakings. To be Taxonomy-aligned, activities must further meet three EU Taxonomy criteria: Technical Screening Criteria, Do No Significant Harm and Minimum Social Safeguard.

Reporting to date under the Taxonomy, which is beginning to emerge for FY2021, offers valuable indications of disclosure requirements in different sectors. For example, Unilever states in a half page disclosure that 0% of its turnover and operating expenditure, and 1% of its capital expenditure, relates to eligible activities. Volkswagen is far more extensive, devoting several pages on its website to the Taxonomy and voluntarily aligning several of its businesses to taxonomy activities. A 2022 study of emerging Taxonomy reporting by Norwegian consultants Nordea found that average eligibility across sectors was only 30%, with low eligibility in sectors such as telecommunications and forestry.4 Firms should note that the decision by the European Parliament to include gas and nuclear energy as sustainable was widely criticised by NGOs and other stakeholders, which has damaged the legitimacy of the Taxonomy and may expose firms to accusations of greenwashing when classifying their activities.

Driven by pressure from institutional investors, and its own concerns about greenwashing in company sustainability reports,5 the SEC issued its proposal for Mandatory Climate Risk Disclosures in March 2022. The proposal draws on the climate risk framework developed by the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). Under the proposed legislation, registrants would be asked to disclose information on, inter alia, climate targets and goals, climate-related risks, risk management processes and climate-related opportunities. Disclosure of absolute and intensity metrics for Scope 1 and 2 Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions, and Scope 3 emissions, if material or the firm has established a reduction target or goal that includes Scope 3 emissions, would also be required.

Furthermore, the legislation would ask registrants to disclose the value of climate related impacts on financial statement line items, such as increased cost of sales due to climate-related supply chain disruption, if the value of the impact is at least 1% of the line item value. This ‘bright line’ materiality threshold was a key issue raised in the recently published consultation responses to the proposed legislation. Concerns were also expressed about the proposed timeline, which requires large accelerated filers to begin reporting on climate risks in FY2023. Accelerated and non-accelerated filers would report from FY2024 and smaller reporting companies in FY2025. If the registrant is subject to Scope 3 requirements, these requirements are to be met one year after the above timelines. This proposed timeline will take affect if the SEC adopts the climate disclosure rules by the end of 2022.

The forthcoming EU CSRD is the most extensive piece of sustainability reporting legislation to date, ambitious in scope and content, with significant new governance implications for firms.

Scope: The EU’s previous iteration, the NFRD, applied to less than 12,000 ‘public interest’ firms. The CSRD will cover an expected 50,000 firms, including “large companies”, a category incorporating SMEs if they satisfy at least two of the following criteria: > 250 employees, > €40m turnover and > €20m balance sheet. Further, non-European companies generating net turnover of €150m or more in the EU and with at least one subsidiary or branch in the EU, will be subject to the CSRD. Companies already subject to the NFRD would be expected to begin reporting from FY2024, followed in FY2025 by large companies not already subject to NFRD, and listed SMEs in FY2026. For non-EU companies, FY2028 is proposed as the earliest reporting date.

Content: While precise disclosures are subject to public consultation and final approval, drafts suggest that the CSRD will be far more challenging than the NFRD. For example, it is likely that firms will need to supply Scope 3 GHG emissions reporting data, relating to its upstream and downstream operations, for example business travel or purchased goods and services, for up to 80% of its Scope 3 emissions. For many firms, particularly in the professional services or consumer goods industries, Scope 3 emissions make up the bulk of their carbon footprint and are notoriously difficult to measure. A 2021 study estimated that 50% of Scope 3 emissions in the Tech sector for example are unrecorded.6

Governance: The CSRD will require independent verification of ESG information by a registered assurance provider and also that the information be included in the Directors’ report, making Directors responsible in writing for ESG performance.

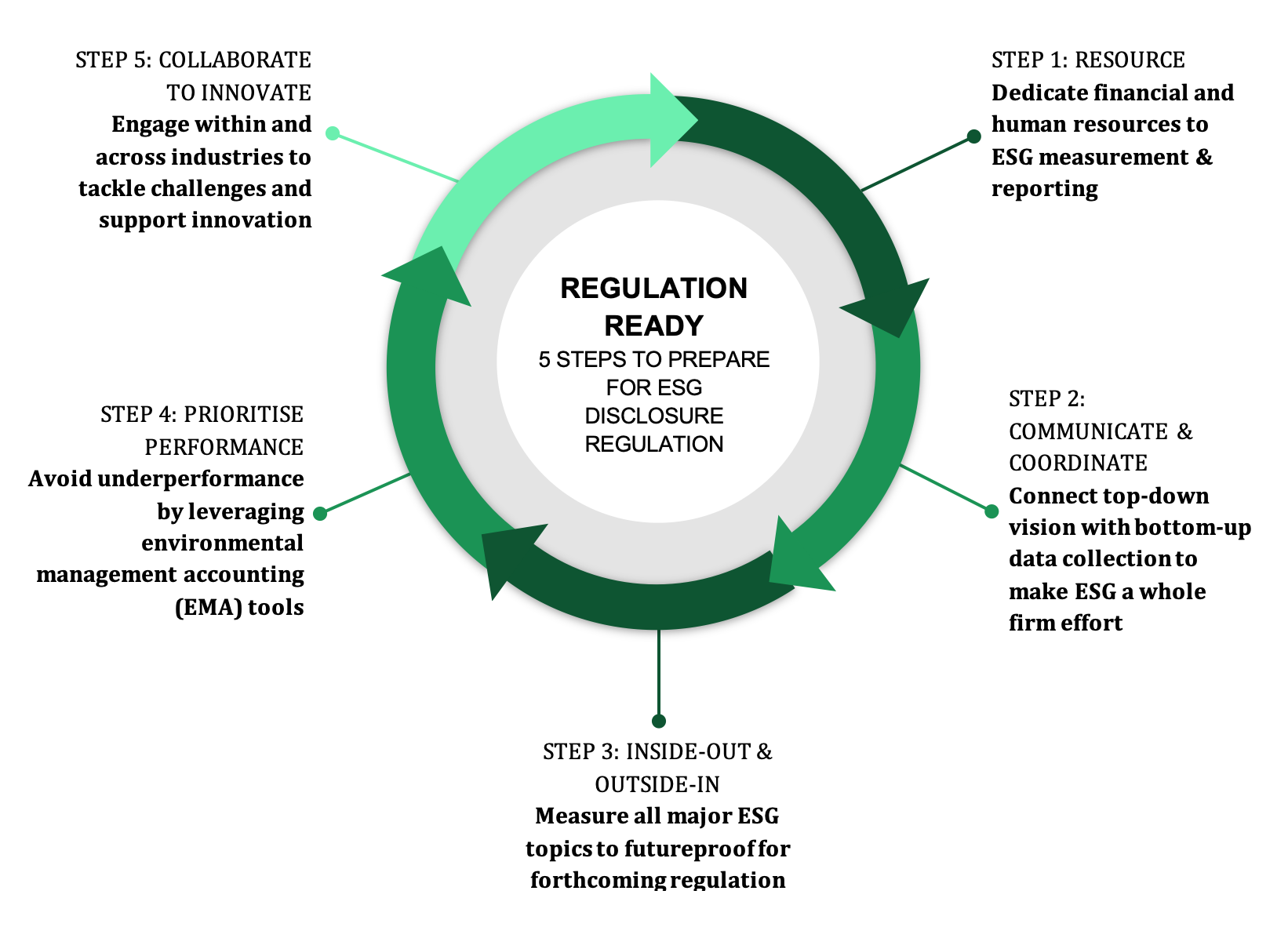

The Regulation Ready model (Figure 1) summarises the five actions firms must take to prepare for new ESG disclosure regulation, with further detail and examples below. These interconnected governance, strategic and management control actions are appropriate preparation for any forthcoming ESG legislation.

Figure 1: Regulation Ready: 5 Steps to Prepare for ESG Disclosure Regulation

1. Resource

Regulation can act as a motivating factor to drive investment in the people, processes and systems required to gather and report ESG data. Many firms still rely on one ‘sustainability champion’; now everyone in the organization must be a sustainability champion. ESG accounting must be resourced and managed like financial accounting, whether in-house or through external consultants.

The CSRD requirement that ESG data be independently verified is leading traditional assurance providers such as large accountancy firms to rapidly expand their sustainability assurance offerings. However, non-accounting assurance providers, such as engineering and environmental consultancies, stakeholder panels, NGOs and academic institutions, should also be considered, as they can provide expertise on specific issues and can boost legitimacy with external stakeholders.7 As these providers expand their offerings, competition will drive increased quality and choice of assurance provider for reporting firms.

2. Communicate & Coordinate

ESG must connect multiple departments including operations (gathering and collating data), finance (budgeting and analysis), human resources (employee data and engagement), marketing (reporting) and C-suite (strategy). Coordinating top-down vision and KPIs with bottom-up data collection and analysis can help to avoid internal ambivalence and resistance.8

The EU Taxonomy can be clearly linked to organisational strategy and leveraged to achieve C-Suite and Board buy-in, as taxonomy eligibility and alignment will help firms to attract capital. Investment firms and asset managers will be required to disclose the extent to which their portfolio aligns with the Taxonomy and large institutional investors such as BlackRock have been vocal in their support of the regulation.

3. Inside-Out & Outside-In

Firms often begin ESG engagement by identifying key stakeholders and, with the help of a reporting framework, identify indicators to be measured. However, ESG accounting and reporting is an inside-out and outside-in process.9 Relying only on an outside-in, stakeholder approach will result in firms missing some of the areas regulation will require them to address. Taking an inside-out approach, firms begin by conducting an ESG audit, identifying the data points required to measure key ESG indicators. This has the dual effect of reducing the risk of missing important disclosures and ensuring that all levels of the firm are involved in planning and data gathering.

One of the key assumptions underpinning the EU CSRD is “double materiality”, whereby the firm must consider not just the impact of ESG risks on the firm itself but its holistic ecological and social impacts. In 2021, communications firm Telefónica conducted an inside-out and outside-in double materiality analysis, incorporating extensive engagement with internal and external stakeholders, which allowed it to reclassify and reprioritise its ESG issues based on both their impact on the firm and on the environment and society.

4. Prioritise Performance

ESG disclosure does not equate to ESG performance.10 Increasingly powerful stakeholders, including activist shareholders and investors, policymakers and socially aware consumers, are now focused on ESG performance - reduction of GHG emissions or diversity metrics for example. Traditional performance management tools such as budgeting, variance analysis and performance related incentives can be adapted to apply to ESG performance.11 This minimises the increasing risks of failing to perform in crucial areas such as climate or governance.

The consequences of underperformance on ESG are clearly evident in the increasing exposure of the oil and gas industry to the risks of legal action and stranded assets. In 2021, a Dutch court ordered Shell to reduce 45% of emissions by 2030, including Scope 3 emissions, in response to a case taken by multiple NGOs and campaigners. Furthermore, despite short-term profit increases due to the Russian war on Ukraine, it is estimated that the industry is at risk of stranded assets to the value of US$1.4 trillion as nation states transition to renewable energy.12

5. Collaborate to Innovate

Collaboration within and across industries can help to tackle typical challenges such as costs and knowledge gaps but also support innovation for sustainability. There is value in both joining existing networks and brokering new initiatives. Sustainability requires us to challenge programmed knowledge and established expertise.13 Including a diverse range of actors in networks supports legitimacy and enables knowledge exchange from different perspectives.

In collaboration with the United Nations, Google has been one of the leaders in developing the 24/7 Carbon Free Energy Compact, wherein participants including private, public and third sector organisations, are working together to understand how firms can generate their own renewable energy, without reliance on carbon offsets. Collaboration can also open up enormous opportunities. The Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), announced during the COP26 climate summit in 2021, demonstrates in its Net Zero Financing Roadmap the opportunities for collaborative innovation in sectors as diverse as solar energy, habitat restoration and alternative proteins.14

The case for reporting is often framed as a reputational risk of non-compliance, but the risk is not just one of non-compliance but of non-engagement with sustainability. The consequences of climate change are increasingly evident and are happening at greater scale and speed than scientists expected. This equates to multiple and varied business risks, as captured by the TCFD framework of physical and transition related risks. Transition risks refer to the policy, legal, technology and market changes associated with the transition to a low-carbon economy. Physical risks include the acute risk of extreme weather familiar to all following the recent unprecedented heatwaves, floods, hurricanes and drought, and the chronic risks of long-term climate change such as sea-level and temperature rise. The severity of the risks is such that climate action failure, extreme weather and biodiversity loss are the top three 2022 global risks identified by the World Economic Forum. SwissRe has calculated that if climate mitigation measures are not taken, the world economy could lose up to 18% of GDP.15 These risks affect different sectors in different ways. The tourism sector will be heavily affected by sea level rise; cities such as Amsterdam, Venice and Bangkok could be underwater by 2030,16 while agriculture will suffer from biodiversity loss; over 60% of the world’s coffee species are close to extinction.17

In recent years climate has been a focus for regulators as pressure to reduce emissions at nation state level intensifies. Looking ahead however, firms can expect a growing emphasis on social issues. The EU has mooted a social taxonomy and has drafted corporate due diligence legislation which would require firms to report on human rights in their supply chains, while the SEC is considering legislation on corporate board diversity. In September 2022 the EU also proposed a ban on producing or importing products made with forced labour.

Rigorous disclosure requirements and growing stakeholder and investor pressure mean that ESG reporting must become a business priority. For firms in all sectors, sustainability is a question both of species survival and of business survival. It is time, as Greta Thunberg warned the World Economic Forum in 2019, for us to act as though the house is on fire.

Jackson, G., Bartosch, J., Avetisyan, E., Kinderman, D. and Knudsen, J.S., 2020. Mandatory non-financial disclosure and its influence on CSR: An international comparison. Journal of Business Ethics, 162(2), pp.323-342. Tang, S. and Demeritt, D., 2018. Climate change and mandatory carbon reporting: Impacts on business process and performance. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(4), pp.437-455.

Carrots&Sticks. 2022. Sustainability reporting instruments worldwide. Available: carrotsandsticks.net. (Accessed 2022, August 09).

Communications from the EU as of July 2022 suggest FY2024 as the first applicable date for CSRD reporting but FY2023 is technically still possible (Council of the EU. 2022, New rules on corporate sustainability reporting: provisional political agreement between the Council and the European Parliament. Available https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/06/21/new-rules-on-sustainability-disclosure-provisional-agreement-between-council-and-european-parliament/. Accessed 2022, August 09).

Nordea. 2022. A first look at companies’ EU Taxonomy reporting. Available: https://www.nordea.com/en/news/a-first-look-at-companies-eu-taxonomy-reporting (Accessed 2022, August 09).

Ramonas, A. 2022. Corning, Polaris Pressed on Climate Reporting as SEC Wraps Rules. Bloomberg Law (Online). Available https://news.bloomberglaw.com/securities-law/corning-polaris-pressed-on-climate-reporting-as-sec-wraps-rules (Accessed 2022, September 19).

Klaaßen, L. and Stoll, C., 2021. Harmonizing corporate carbon footprints. Nature communications, 12(1), pp.1-13.

Farooq, M.B. and de Villiers, C., 2018. The shaping of sustainability assurance through the competition between accounting and non-accounting providers. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 32(1), pp.307-336.

Slager, R. and Gond, J.P., 2022. The politics of reactivity: Ambivalence in corporate responses to corporate social responsibility ratings. Organization Studies, 43(1), pp.59-80.

Schaltegger, S., 2012. Sustainability reporting beyond rhetoric: linking strategy, accounting and communication. Contemporary issues in sustainability accounting, assurance and reporting, pp.183-196.

Dillard, J. and Vinnari, E., 2019. Critical dialogical accountability: From accounting-based accountability to accountability-based accounting. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 62, pp.16-38.

Gibassier, D. and Alcouffe, S., 2018. Environmental management accounting: the missing link to sustainability?. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal, 38(1), pp.1-18.

Semieniuk, G., Holden, P.B., Mercure, J.F., Salas, P., Pollitt, H., Jobson, K., Vercoulen, P., Chewpreecha, U., Edwards, N.R. and Viñuales, J.E., 2022. Stranded fossil-fuel assets translate to major losses for investors in advanced economies. Nature Climate Change, pp.1-7.

Brook, C., Pedler, M., Abbott, C. and Burgoyne, J., 2016. On stopping doing those things that are not getting us to where we want to be: Unlearning, wicked problems and critical action learning. Human Relations, 69(2), pp.369-389.

Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero. 2021. Financing Roadmaps. Available: https://www.gfanzero.com/netzerofinancing (Accessed 2022, August 09).

Swiss Re Group. 2021. World economy set to lose up to 18% GDP from climate change if no action taken, reveals Swiss Re Institute’s stress-test analysis. Available: https://www.swissre.com/media/news-releases/nr-20210422-economics-of-climate-change-risks.html (Accessed 2022, August 09).

Cunningham, E. 2021. 9 cities that could be underwater by 2030. Available: https://www.timeout.com/things-to-do/cities-that-could-be-underwater-by-2030 (Accessed 2022, August 09).

Davis, A.P., Chadburn, H., Moat, J., O’Sullivan, R., Hargreaves, S. and Nic Lughadha, E., 2019. High extinction risk for wild coffee species and implications for coffee sector sustainability. Science advances, 5(1), p.eaav3473.