California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier academic management journal published at UC Berkeley

by Konstantinos Bozos, Vicky Bamiatzi, and G. Tomas M. Hult

Image Credit | Micheile Dot Com

Managers must constantly and relentlessly figure out how to best use resources to shape the company’s financial performance. Companies strive to implement decisions that result in the efficient use of resources for the products and services they seek to make for a competitive and dynamic marketplace. Using too many or too much of certain resources is not cost-sustainable over time. On the flip side, not using available or idle resources can make the company’s value chain inefficient and its position in the marketplace ineffective.

“Acquisitions of Startups by Incumbents: The 3 Cs of Co-Specialization from Startup Inception to Post-Merger Integration” by Nir N. Brueller & Laurence Capron. (Vol. 63/3) 2021.

“Changing the Work of Innovation: A Systems Approach” by George S. Day & Gregory Shea. (Vol. 63/1) 2020.

For optimal strategic balance, companies need to adopt a managerial strategy that is simultaneously cost-sustainable, value-chain efficient, and marketplace effective. This is where organizational slack – resources above those required for normal company operations – has become a focus for many companies and stakeholders (e.g., investors). The question is always on maximizing the use of resources, holding resources in competitive inventory, and how to best leverage the uniqueness of resources available to a company.

For example, Apple, Alphabet (Google), Amazon, and Microsoft regularly hold between $50 and $200 billion in cash on hand. Cash allows these companies to be ultra-responsive when capital-intensive opportunities arise. Amassing cash can provide competitive leverage but it can also be a performance detriment. Now, a company’s cash-on-hand is just one of several potential resources that a company can have. Overall financial strength, enterprise knowledge, and workforce skills are some other resources that are valuable to companies.

But proactive and responsive competitiveness is less about types of resources and more about the slack a company has in those resources. Slack resources are a cushion against changes in the external environment (cf. Berkshire Hathaway), can be used as an internal problem-solving mechanism, and can be used as a facilitator of strategic change. However, a company that possesses (excess) slack resources also exhibits higher levels of inefficiency (i.e., resulting in suboptimal bottom-line performance).

What many managers fail to understand is that an emphasis on the slack resources per se rather than their configuration is fraught with pitfalls. The company’s direction and speed of growth depend on how managers configure slack resources, not just the availability of excess, unutilized resources. We must also consider what resource levels are necessary. Companies can have different levels of unutilized resources, not all of which can be considered available and usable slack.

These slack resources can be attributed to distinct resource configurations pertinent to a company’s success. For instance, it is normal for retailers to hold unutilized cash or cash equivalents since a certain proportion of cash is the working capital necessary for day-to-day operations. Another example is companies in capital-intensive industries (e.g., energy, mining, oil and gas, utilities) that require larger capital expenditures and have different resource configurations than those in non-asset-intensive industries (e.g., retail and service).

Different types of slack resources and their (synergistic) interactions are unfortunately often removed from a manager’s input into the decision-making equation. The input into a manager’s decision-making should be that resources are always to be distinguished between those that are highly context, company-specific, and less easily utilized (i.e., human resources, operational capabilities) and those that are generic and can be quickly utilized to fuel growth (i.e., cash-on-hand).

Practically, this means that the two extremes are available slack – uncommitted resources with high managerial discretion like cash-on-hand – and recoverable slack – low discretionary, absorbed resources, representing a company’s operational capacity. Importantly, low and high-discretion resource-slack coexist and are often used together. Managers often assume that available and recoverable slack are additive. This view is oversimplified and does not create an optimal strategy.

Having high levels of both available and recoverable slack will not only be wasteful but to some extent even unattainable (i.e., public utilities typically exhibit high recoverable slack, but rarely high available slack). Similarly, while low levels of unutilized recoverable slack may be desirable for efficiency standards, growth cannot be achieved without the necessary surplus of assets (i.e., cash-on-hand) that is easily redeployed.

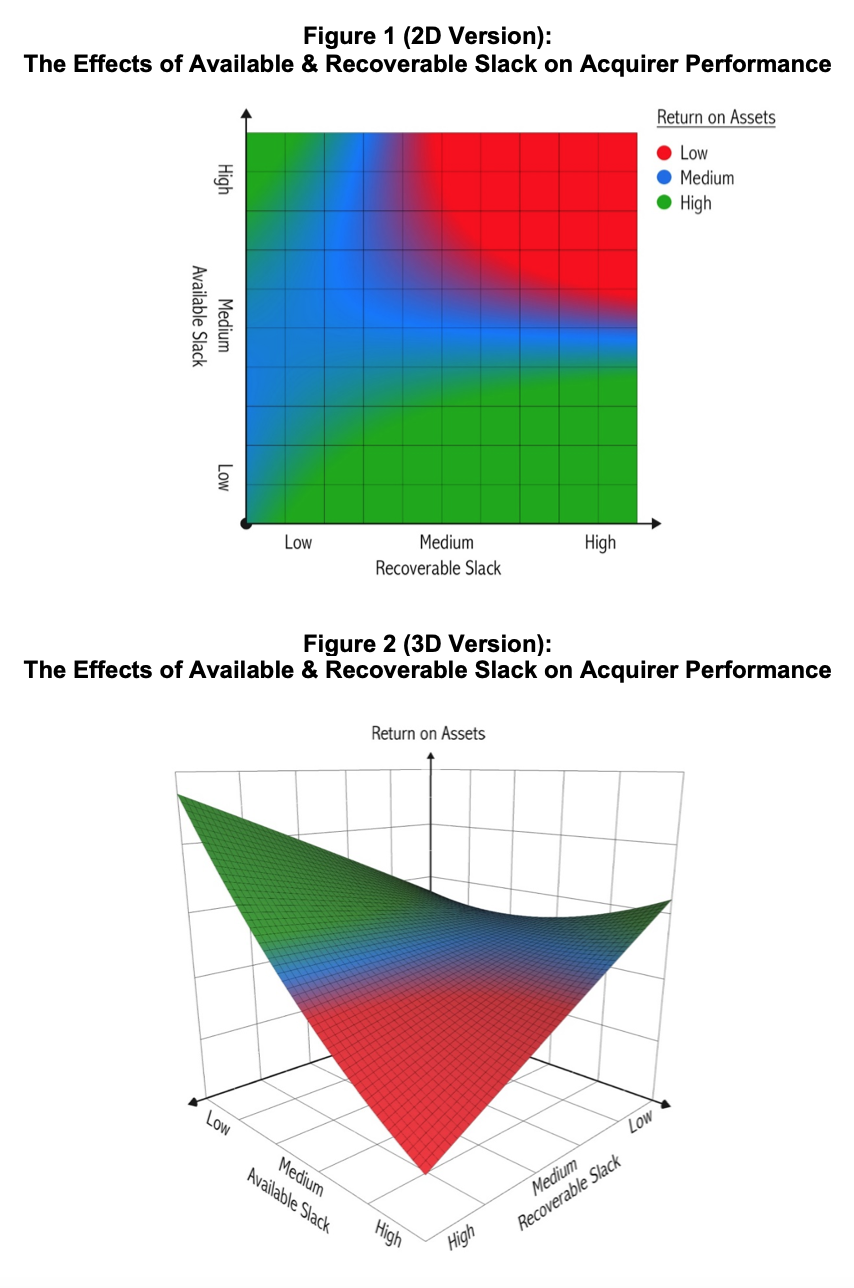

As an example, we examined a sample of 3,851 large acquisitions by companies in the United States over a 15-year period and calculated mean Return on Assets (ROA) to isolate the effects on the acquirer’s performance three years after the M&A deal (i.e., Mergers and Acquisitions). We find that post-acquisition performance is a function of the acquirer’s pre-existing slack, with available and recoverable slack exhibiting both independent and conditional effects on performance.

While independent slack is detrimental to performance, with congruent levels of both types of slack (available and recoverable) exacerbating the negative performance effects, acquirers with incongruent slack levels can outperform all others. Combining a tight and efficient operation (low levels of recoverable slack) with leeway in working capital (high levels of available slack) maximizes post-acquisition performance (i.e., ROA).

In conclusion, in the context of Mergers and Acquisitions (M&As), the traditional expectations of resource efficiency are not valid. Instead, achieving the right balance between efficiency – by keeping ‘sticky’ resources at low levels – and operational flexibility, offers the optimal and maximum post-deal benefits to an acquirer. Figure 1 (2D version) and Figure 2 (3D version) illustrate the effect of available and recoverable slack on an M&A acquirer’s performance.