California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier academic management journal published at UC Berkeley

by Anastasia Koslova, Riccarda Joas, and Dr. Isabell Welpe

Image Credit | Austin Distel

“Materiality Assessment Is an Art, Not a Science: Selecting ESG Topics for Sustainability Reports” by Jilde Garst, Karen Maas, & Jeroen Suijs. (Vol. 65/1) 2022.

“What Impact? A Framework for Measuring the Scale and Scope of Social Performance” by Alnoor Ebrahim & V. Kasturi Rangan. (Vol. 56/3) 2014.

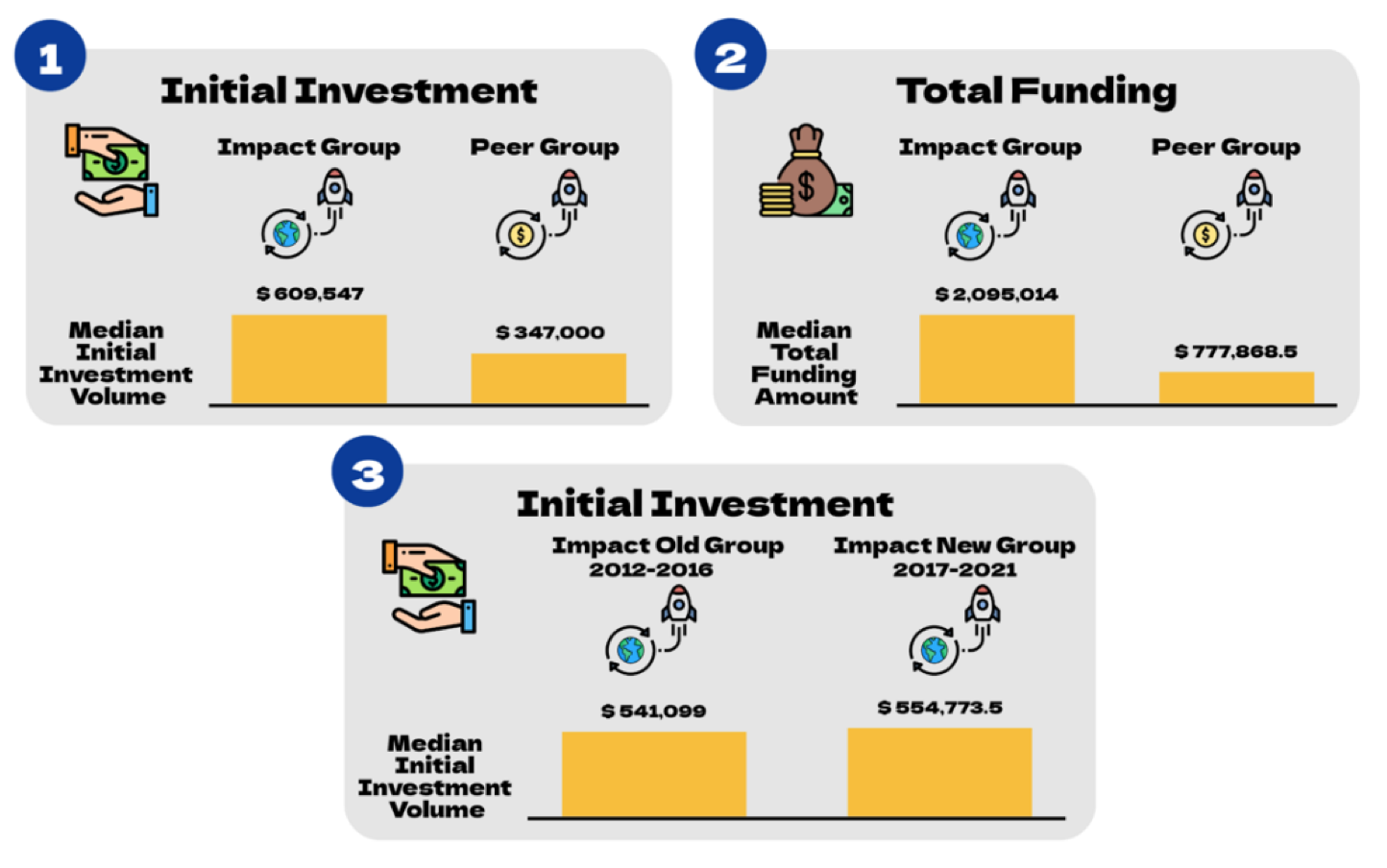

Since the late 2000s an alternative asset class called impact investing is rapidly evolving and gaining more and more interest among scholars and practitioners of private and public capital markets. The trend is rooted in agendas such as the Sustainable Development Goals by the United Nations or the action plan on financing sustainable growth by the European Commission, which fostered the foundation of impact start-ups that tackle the tasks outlined in these agendas. According to the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) the impact investing market, which amounted to ~ 1 trillion USD of assets under management in 2021, is expected to rise at a two-digit compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) over the next years.1,2 In parts this is further accelerated by a new generation of investors, which are not solely interested in materialistic goals,3 but rather want to contribute to society and treat people ethically.4 Given the asset class evolved only recently, there is limited scientific evidence how the investment into start-ups with impact manifests on the balance sheet of venture capital firms (VCs). In an empirical analysis we find that start-ups with impact are evolving positively, demonstrating a median amount in initial investment and total funding, which was twice as high as the volumes for start-ups without declared impact. Given that the current ESG trend5 and demand for impact start-ups will continue over the next decade, VCs that invest into start-ups with declared impact can expect a positive effect on their balance sheets.

The MSCI clusters the broad field of ESG investing into three separate investor objectives, with impact investing being one of them. Followingly, it differentiates the impact objective by its focus on creating social and/or environmental benefits while generating a financial return.6

The International Finance Corporation defines impact investing by specifying the following three criteria that need to be fulfilled to be classified as an impact investor:7

An intent for achieving social and/or environmental goals through the investment needs to be proven.

A credible narrative on how the investment contributes to achieving the intended goal needs to be demonstrated.

They have a system of measurement in place that links their intent and the contribution of their investment to improvements in social and environmental outcomes delivered by the enterprise in which the investment was made.

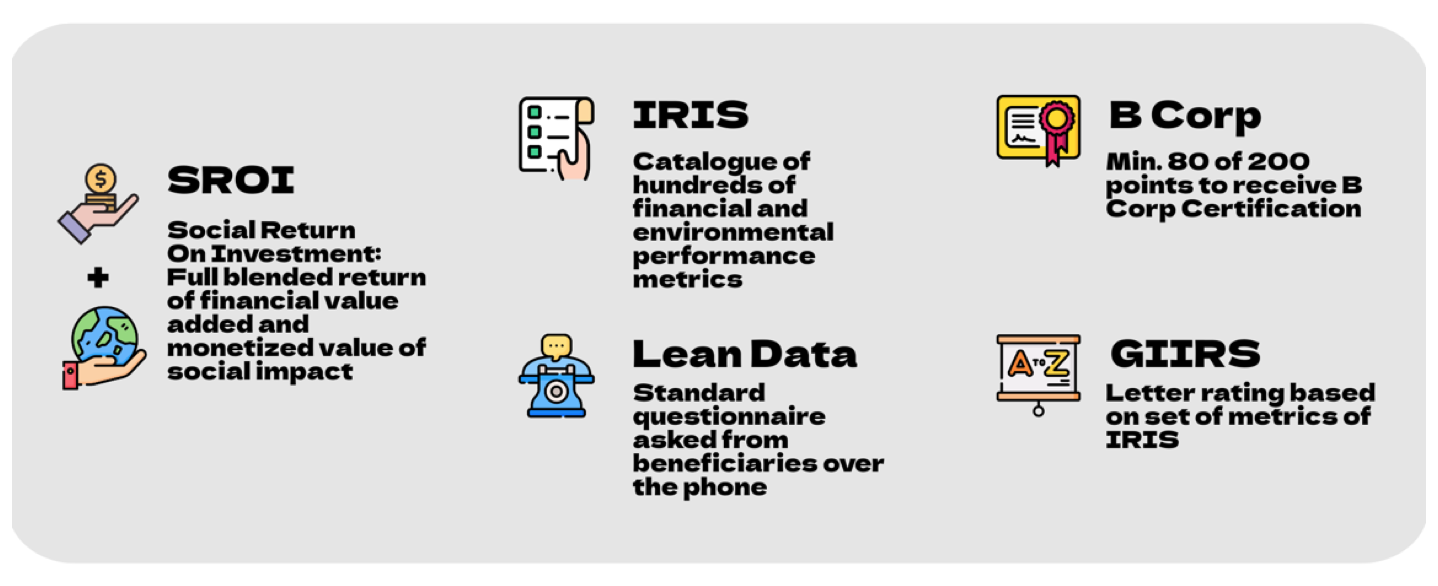

Several industry leaders developed common standards and performance metrics to be able to measure this social- and environmental performance. One of the first actors was the Robert Enterprise Development Fund, which developed the Social Return on Investment framework in 2001. For this, the full blended value of a project needs to be calculated by combining the financial value added of a project with a monetized value of the social impact.8 Another approach to measure impact was developed by the Global Impact Investing Network. It formed the IRIS – the Impact Reporting and Investment Standards – that provide a catalogue of hundreds of financial and environmental performance metrics that constitute a common set of definitions in the field of impact investing.9 The Acumen Fund developed the Lean Data methodology, that includes the input of beneficiaries of the social/environmental impacts. Here, information is collected from the beneficiaries via the phone based on a standard questionnaire. The B Lab created a certification process to become a so-called B Corporation. For that, it developed 200 points to be reached in the segments: governance, workers, community, environment, and customers, of which 80 points need to be reached to receive a B Corp Certification. Another tool developed by the B Lab is the GIIRS – the Global Impact Investing Rating System.10 Lastly, other measurement systems used are, e.g., the SDG Impact Standards from the UNDP or the GRI Standards.

In our study we analyzed the effect that start-ups with a social/environmental impact have on VCs, especially from a financial perspective. Therefore, the intent of VCs to invest in impact start-ups, the growth rate of impact start-ups and the trend towards impact investing in recent years was analyzed. For testing this, we formulated three hypotheses:

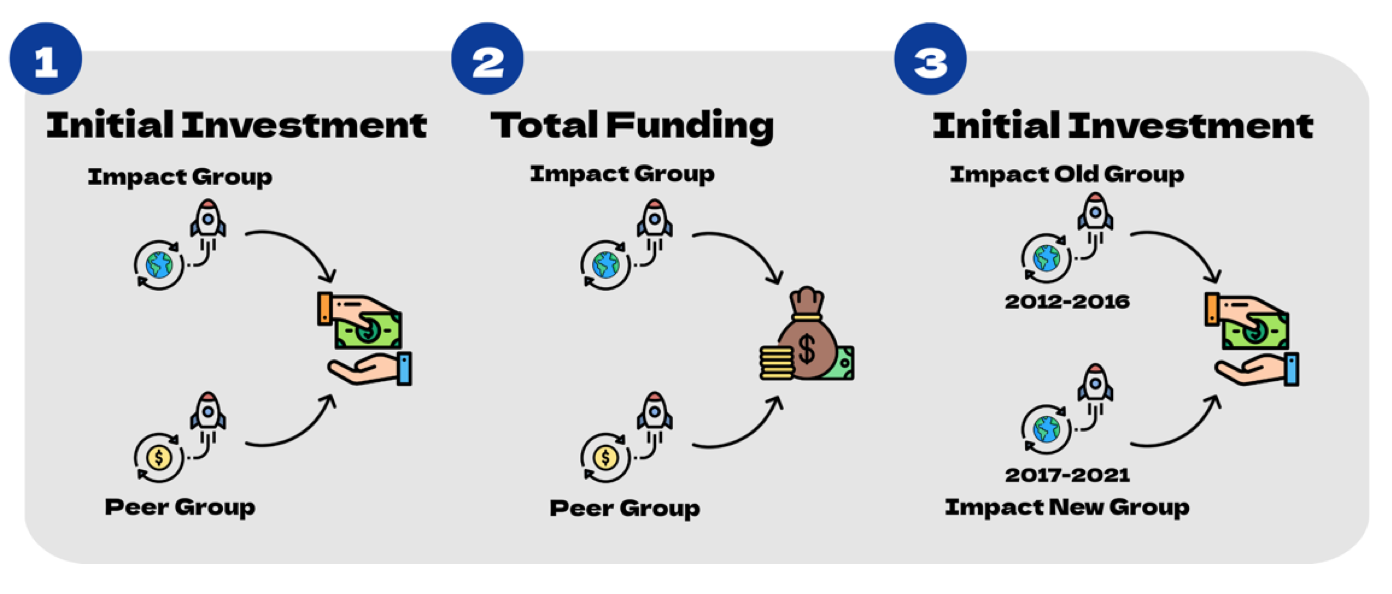

H1: The initial investment amount received by start-ups with a social and/or environmental impact is lower compared to start-ups without impact.

H2: The total funding amount received by start-ups with a social and/or environmental impact is lower compared to start-ups without impact.

H3: Start-ups with social- and/or environmental impact founded between 2017 and 2021 will receive more initial investment than start-ups with social and/or environmental impact that have been founded between 2012 and 2016.

The hypotheses were tested using an independent samples t-test on the difference in means of the initial investment amount and the total funding amount between the impact and the peer group. The impact group was formed by using start-ups that have a B Corp Certificate and are active in the B2C sectors in Europe. The peer group was formed by start-ups that do not have a B Corp Certification but are active in the same sectors and regions (i.e., EU and UK). The data used for the analysis was retrieved from the data platform Crunchbase and the final sample consisted of ~ 3,700 start-ups. Given the nature of start-ups, the distribution of the test variable was not normal, hence the median was used as a measure for central tendency. Additionally, the variables were logarithmically transformed before conducting the independent samples t-test, to adjust for the non-normal distribution. The impact and the peer group have an approximately equal distribution across founding years to control for general market effects. The results indicate that start-ups that have a social- and/or environmental impact receive significantly higher initial investments (H1), as well as total funding from investors (H2), when compared to the peer group. A positive trend towards impact investing in recent years was analyzed comparing impact start-ups that were founded between 2017 and 2021 to impact start-ups founded between 2012 and 2016. The more recently founded group of impact start-ups received a higher amount in initial investment on average, however this result was not found to be significant (H3).

The main challenge in empirically studying impact start-ups is the sample itself, given the unique nature of start-ups (i.e., their founders, business model, etc.). In our study we tried to control for this aspect via scale by including ~80 impact start-ups and ~3,600 peers. We built the impact group by including corporations that achieved certification as “B Corporation” by the B Lab. In supplementary analyses we controlled whether the certification had a signaling effect and influenced initial investment. The assumption was refuted as most of the companies had their initial investment round before getting the B Corp Certification. We reflect that our findings are not generalizable for all start-ups that claim to have impact, given that corporations which seek and achieve certification might be inherent more ambitious and successful later. This gives rise to the issue that there is currently still a fragmented landscape of frameworks for measuring impact. Similarly, corporations often struggle which environmental, social, and governance (ESG) topics to include in their reporting and which are less material. Given the maturing nature of impact start-ups and investing, even further alignment as well as consolidation of standards and performance metrics is needed.

In our study we found that impact start-ups have a positive effect on the balance sheet of VCs, when measuring performance via the total amount of funding or external validation, i.e., the ability to attract follow-on investors. The crux however is the determination of an impact start-up, which is – despite efforts for harmonization – still subject to a fragmented landscape of frameworks and reporting standards.

GIIN. (2022). Sizing the Impact Investing Market. Available from: https://thegiin.org/assets/2022-Market%20Sizing%20Report-Final.pdf

The Business Research Company. (2023). Impact Investing Global Market Report 2023. Available from: https://www.thebusinessresearchcompany.com/report/impact-investing-global-market-report

Barber, B. M., Morse, A., & Yasuda, A. (2021). Impact investing. Journal of Financial Economics, 139(1), 162-185.

Claire, L. (2012). Re-storying the entrepreneurial ideal: lifestyle entrepreneurs as hero? Tamara: Journal for Critical Organization Inquiry, 10, 31.

Pástor, L., Stambaugh, R., Taylor, L. (2022). Dissecting green returns. Journal of Financial Economics, 146(2), 403-424.

MSCI. (2022). ESG 101: What is Environmental, Social and Governance? Available from: https://www.msci.com/esg-101-what-is-esg

IFC. (2021). Investing for Impact - The Global Impact Investing Market 2020. Available from: https://bundesinitiative-impact-investing.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/2021-InvestingforImpact_FINAL2_web.pdf

Nicholls, A. (2009). ‘We do good things, don’t we?’: ‘Blended Value Accounting’ in social entrepreneurship. Accounting, organizations and society, 34(6-7), 755-769.

Reisman, J., Olazabal, V., & Hoffman, S. (2018). Putting the “impact” in impact investing: The rising demand for data and evidence of social outcomes. American Journal of Evaluation, 39(3), 389-395.

Wilburn, K., & Wilburn, R. (2014). The double bottom line: Profit and social benefit. Business Horizons, 57(1), 11-20.