California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier professional management journal for practitioners published at UC Berkeley Haas School of Business.

Image Credit | Timothy Hales Bennett

Meta’s decision to focus on the Metaverse was controversial from the beginning. A year and a half later, Meta is facing harsh criticism. The reality is that we might be still far from the Metaverse that is envisioned by Meta and its followers. With so much at stake, it is more important than ever for business leaders to critically assess the viability of Meta’s vision against their own Metaverse strategy.

“A Brief History of Artificial Intelligence: On the Past, Present, and Future of Artificial Intelligence” by Michael Haenlein & Andreas Kaplan. (Vol. 61/4) 2019.

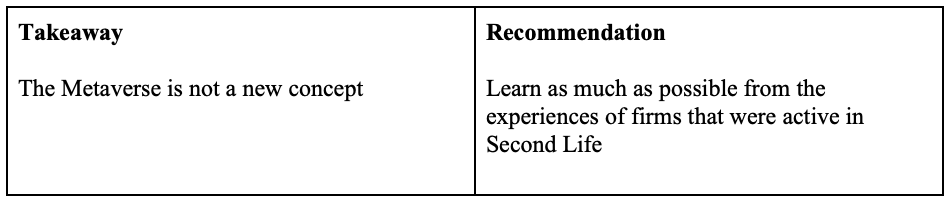

Surprisingly, many people are unaware that the Metaverse concept is not entirely new. We experienced something similar approximately 15 years ago. Maybe it is time to turn to history so we can have a better understanding of what might lie ahead.

Fast rewind…

In 1992, Neal Stephenson published Snow Crash. In this novel, he told the story of a character called Hiroaki Protagonist who physically lived in Los Angeles but spent most of his time in a virtual world called the Metaverse.

In the early 2000s, what we now call metaverses used to be known as virtual worlds. In virtual worlds, people already appeared in the form of avatars and could interact with objects and other avatars. There are major differences between virtual worlds and the Web. When people go to a website for shopping, no one else is there with them. When they use virtual worlds, they can look around and see other people. There are no physical limitations. The interactions are also richer and more immersive.

Second Life, one of the most popular virtual worlds, had an estimated 64.7 million registered users. It was created by a San Francisco-based firm called Linden Research in 2003. From the beginning, Philip Rosedale, the founder of Linden Research, made clear Snow Crash was a major inspiration for Second Life. Importantly, Second Life is not a game. It is a full-blown virtual world in which users hold the copyright of the content they create. They can sell it to other users in exchange for a virtual currency called Linden dollars.

In the mid-2000s, many firms rushed into the new virtual economy. Business opportunities seemed too good to ignore in an unregulated market that was open to everyone. Traditional companies saw Second Life as a new and promising outlet for their existing activities. Pure virtual companies developed new value propositions that were tailored to virtual worlds. The sky was the limit. Many claimed that Second Life would soon replace the Web. Second Life peaked in 2007 with 1 million monthly users.

However, Second Life did not live up to expectations and quickly lost momentum. By 2008, most companies had exited it. While people kept creating avatars to check what Second Life was about, they were often lost in ghost cities with empty storefronts. Today, Second Life still exists. However, it only has a few thousand dedicated users. Companies never came back. Until now…

Our objective is to help readers understand the past, so they can better prepare for the future. Even though there are differences between now and then, we can learn a lot from the experience of firms that were active in Second Life.1 This post is based on an in-depth analysis of more than 60 case studies of firms that launched business activities in Second Life. We draw on these experiences to dissipate some myths. We also offer practical recommendations of what companies need to consider as they enter the Metaverse.

In February 2022, JP Morgan set up a virtual lounge in the platform Decentraland and boldly claimed that it was the first leading bank with a presence in the Metaverse. The following month, HSBC announced that it had purchased virtual real estate in the metaverse platform Sandbox. Six months later, DBS, one of the most innovative digital banks in the world, announced that it had also acquired a plot of virtual land in Sandbox. Many more banks have already revealed plans to join the Metaverse bandwagon.

It is tempting to conclude that it is the first time that banks dip their toes into virtual worlds. However, many banks were enthusiastic adopters of Second Life. ABN AMRO Bank opened a virtual branch to provide financial advice to its customers. ING Group created Our Virtual Holland, a virtual space where it could interact with a community of entrepreneurs. Wells Fargo developed games to educate people about managing their personal finances. The BCV (Banque Cantonale Vaudoise), a Swiss bank, used the virtual world to share information about their real-world services with their clients. Wirecard bank established a virtual branch allowing customers to access their payment services. These are just a few examples of banks conducting business activities in Second Life.

The excitement surrounding Second Life went far beyond the banking industry. Large IT firms were the first to use Second Life to address their global community. When Sun Microsystems announced that it would make its Java programming language open source, it held the Q&A session with developers in Second Life. Before long, IT firms were joined by firms from other industries. Brands such as Adidas, Ben & Jerry’s, and Coca-Cola saw Second Life as a new playground for marketing experiments. Automobile manufacturers, such as Toyota, launched prototypes in the virtual world. Hospitality chains, such as Starwood Hotels, tested new concepts and sought feedback from users. Retailers such as Circuit City opened virtual stores. The media industry also found interest in the virtual world. Big news companies such as Reuters and CNN opened offices in Second Life to report virtual happenings.

Surprisingly, today’s businesses treat the Metaverse as something completely new. They seem to have totally forgotten their prior experiences in Second Life. The decision-makers and teams who worked on Second Life are probably long gone and could not share their stories. However, Second Life is, without a doubt, the closest thing to the Metaverse that we may anticipate for the near future.

What is different today is that technology is now more advanced than it was in the mid-2000s.2 The use of VR goggles enables immersive 3D experiences. Blockchain technology supports virtual currencies, IP protection, and ownership.3 However, as of now, there are only small differences between current metaverse platforms (such as Decentraland or Sandbox) and Second Life.

Despite the buzz, Second Life never achieved mass adoption. By learning from the failure of Second Life, firms are more likely to avoid reinventing the wheel and making similar mistakes.

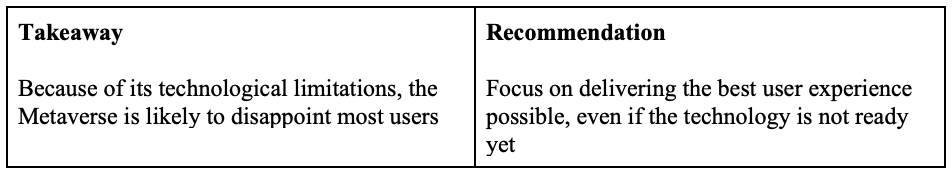

A true Metaverse is at least a decade away. Indeed, a fully immersive environment requires even more advanced VR and AR hardware and software than the ones that are currently available. Future versions of Microsoft Mesh and Meta Horizon Worlds may reach this goal. In the meantime, people will only be able to experiment with early versions of the Metaverse through games such as Robox and Fortnite or virtual worlds such as Sandbox and Decentraland.

How big will the Metaverse be? On the one hand, experts from Gartner have predicted that 25% of people will spend at least one hour a day in the Metaverse by 2026 because it will offer a truly unique and transformative experience that justifies the hype. Whether it is for business or leisure, the Metaverse may have the potential to change how we interact with each other radically.4

On the other hand, many people are still uncomfortable engaging socially with others in virtual worlds. They often prefer “life in the real world”. Living in a virtual world makes sense when you are stuck at home (such as during Covid lockdowns…). When life is back to normal, people are unlikely to spend most of their time in a metaverse. Indeed, there is only so much time for gaming, socializing, working, and learning online.5

Initially, Second Life managed to attract a lot of users. However, only a minority kept using the platform. As a result, many firms could not generate enough traffic on their islands. There were a few exceptions. The two most popular islands were Money Island (a place where Linden dollars were given away) and Sexy Beach (a place with virtual sex shops). As a journalist wrote: “Avatars seem more interested in having sex and hatching pranks than spending time warming up to real-world brands.” Gambling was also a big part of Second Life. It was so popular that the economic activity of Second Life dropped by 25% when Linden Research decided to shut casinos down in July 2007.

An important cautionary tale is that most of the experiences proposed by businesses were not “sticky” enough. That is, there were not enough reasons for users to interact with businesses in Second Life. Replicating in the virtual world what a firm is already doing in the real world is unlikely to be successful. For instance, the virtual stores of Armani were boycotted by Second Life users because they lacked interactivity. In virtual worlds, keeping users engaged is key to success.

Technology has often been blamed for Second Life’s lack of stickiness. The 3D screen-based technology was clunky, and Second Life did not offer a fully immersive experience. Bugs made the overall experience painful. At some point, Time magazine even labeled Second Life one of the five worst websites because of its lack of user-friendliness. It is estimated that between 20 and 30% of first-time users never returned to Second Life because it was too difficult to use.

Even though technology has significantly improved, it still has limitations. For example, in addition to being expensive, VR headsets are not very comfortable to wear during extended periods. More importantly, the Internet is not ready to handle the heavy traffic required by the Metaverse. Having thousands of people interact with each other in a fully immersive world remains technically challenging.

Current predictions about the future market potential of the Metaverse are bullish. JP Morgan estimates that it will exceed $1 trillion in revenues annually. McKinsey&Company predicts that it will generate more than $5 trillion in revenues by 2030. The same report indicates that $ 120 billion will be invested in developing the Metaverse in 2022. These bold predictions add to the hype created by the large investment of Meta in its metaverse project (approximately $10 billion in 2021).

For some, the metaverse represents the future of marketing.6 It is difficult to deny the appeal of the Metaverse now that leading firms such as JP Morgan, Samsung, Walmart, PricewaterhouseCoopers, Adidas, and Gucci have acquired real estate in Sandbox or Decentraland. Some of these fast movers may have a convincing justification to get a head start. However, the promises of big earnings from brand-new technologies have often clouded the judgment of leaders and managers. Jumping on the bandwagon without a proper plan systematically leads to failure.

Looking back at Second Life, the optimistic projections about the future economy of the Metaverse are not entirely unfounded. Second Life’s economy was real, with a two-digit growth over its three most popular years. By 2009, the size of its economy was around $ 567 million, with gross resident earnings (GRE) of $ 55 million. In 2007, the CFO of Linden Lab reported that 45,000 accounts had a positive monthly cash flow. However, only 150 of them generated more than $ 5,000 per month. These creative and technically competent users created most of Second Life’s virtual content. They often resigned from their day job to start a full-time business in Second Life. At some point, the BBC hosted a show in Second Life to cover stories of how people made money in the virtual world. One of them - Anshe Chung - even appeared on the cover of Business Week as the first Second Life millionaire.

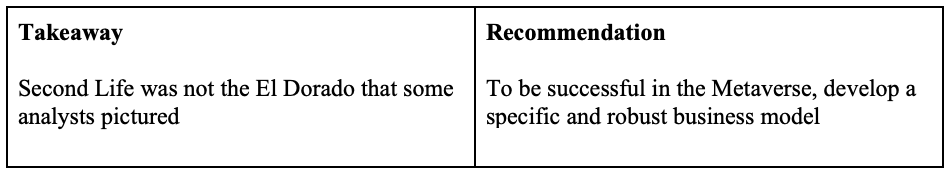

For traditional businesses, the real issue with Second Life is that it was never obvious how they could generate significant profits. Maintaining a strong presence in the virtual world required a lot of resources. Dell was one of the first companies to join Second Life. It built four islands: a factory (where users could build PCs), a theater, a reproduction of the dorm room where Michael Dell founded the company, and a nursery. As a consultant who used to work on this project put it: “if customers had followed, there would have been no problem, but there wasn’t enough usage of the space to justify the resources needed to keep it dynamic.” The PC manufacturer exited Second Life in 2007.

A handful of firms managed to develop offerings tailored to the needs of Second Life users. For instance, Telecom Italia opened four islands in Second Life. It also introduced a product called First Life Communicator that enabled avatars to call each other and exchange text messages. Some companies used Second Life for market research purposes. For instance, Starwood Hotels created a virtual concept hotel called Aloft in Second Life and observed users’ reactions. Based on their feedback, Starwood altered the original concept. By using Second Life to test its new concept, the hotel chain saved money because it did not have to build a physical mockup of the hotel.

The most successful firms in Second Life used gamification to attract and retain users. For instance, the Weather Channel proposed a trendy attraction that enabled users to play sports (e.g., surfing, cycling, or skiing) in various settings and under challenging conditions (e.g., tsunamis, avalanches, or floods). However, firms essentially used Second Life as a marketing platform. Although virtual worlds can be effective for brand building, most corporate islands were only about billboards and commercials. The main objective was to create brand awareness by giving free virtual goods. Many initiatives lacked proper engagement hooks with the users.

In sum, a key lesson from the rise and fall of Second life is that there is no single approach to doing business in virtual worlds. Most firms’ value creation will be indirect through brand building and awareness. For some, virtual worlds will provide great testbeds to engage with customers and test new concepts without incurring physical limitations. But one thing is clear. Companies that want to make money in the Metaverse cannot just replicate their current activities. Fresh thinking is required to design new business models that create a competitive advantage.

While a “true” Metaverse has the potential to change our lives, it is still too early to predict if it will do so. As Bernard Arnault, the CEO of fashion giant LVMH, recently said:

“To be sure, it’s compelling, it’s interesting, it can even be quite fun… If it’s well done, it can probably have a positive impact on brands’ activities… I would just say, beware of bubbles. I remember this from the early days of the internet, at the beginning of the 2000s… There were a bunch of would-be Facebooks back then, and in the end, only one of them worked out. So let’s be cautious.”7

Prior experiences with Second Life and other virtual worlds can help us to anticipate many of the challenges that firms will face in the Metaverse. The main one will be to attract and retain users. Although Second Life was early for its time, it provides us with important lessons for the future of the Metaverse.

Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2009). The fairyland of Second Life: Virtual social worlds and how to use them. Business Horizons, 52(6), 563-572; Brown, S. (2022), What Second Life and Roblox teach us about the metaverse, MIT Sloan School, 19 July, https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/what-second-life-and-roblox-can-teach-us-about-metaverse

Lee, L. H., Braud, T., Zhou, P., Wang, L., Xu, D., Lin, Z., … & Hui, P. (2021). All one needs to know about metaverse: A complete survey on technological singularity, virtual ecosystem, and research agenda. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.05352.

Belk, R., Humayun, M., & Brouard, M. (2022). Money, possessions, and ownership in the Metaverse: NFTs, cryptocurrencies, Web3 and Wild Markets. Journal of Business Research, 153, 198-205.

Dwivedi, Y. K., Hughes, L., Baabdullah, A. M., Ribeiro-Navarrete, S., Giannakis, M., Al-Debei, M. M., … & Wamba, S. F. (2022). Metaverse beyond the hype: Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management, 66, 102542.

Stackpole T. (2022). Exploring the Metaverse. Harvard Business Review, 100(4), 146-147.

Hollensen, S., Kotler, P., & Opresnik, M. O. (2022). Metaverse–the new marketing universe. Journal of Business Strategy.

Diderich, J. (2022), WWD, Bernard Arnault cautious on metaverse, WWD, p. 15.

Insight

Seojoon Oh

Insight

Seojoon Oh

Insight

Swetha Pandiri

Insight

Swetha Pandiri