California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier professional management journal for practitioners published at UC Berkeley Haas School of Business.

by David Bach

Image Credit | Alex Radelich

In this note, I offer a framework to help business leaders cope with the duality of geopolitical conflict and stakeholder scrutiny. CEOs increasingly face pressure to take a public stand on complex political issues, including major geopolitical events such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine or the war between Israel and Hamas. This is treacherous terrain. The key to successfully navigating these pressures is understanding why the demand for CEOs to weigh in on hot button issues arose in the first place. Taking a stand on current issues – including on matters of war and peace – is above-all a signaling tool, and CEOs must be clear what they are trying to signal, to whom, and why.

“Frame or Get Framed: The Critical Role of Issue Framing in Nonmarket Management” by David Bach & Daniel J. Blake

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, many CEOs found their voice on matters of geopolitics, condemning Putin’s aggression and standing firmly with the Ukrainian people. However, a mere 18 months later, many of these same leaders struggled to navigate the moral quagmire resulting from Hamas’ brutal attack on Israel and the humanitarian catastrophe in Gaza caused by Israel’s military response. “When must we take a stand? Do we really have to have a position on everything? When is it better to remain silent?” I have heard these questions frequently from dazed CEOs since the events of October 7. This note, and the framework sketched below, are informed by conversations with dozens of executives and board members, particularly in the context of the current conflict in the Middle East.

CEO political activism, defined as “a business leader’s personal and public expression of a stance on some matter of current social or political debate,” is a phenomenon largely of the last decade. Prominent examples of CEOs taking a public stance on high-profile political issues include PayPal CEO Dan Schulman’s 2016 cancelation of a major North Carolina investment after the state’s adoption of a law widely seen as anti-LGBTQ, Apple’s Tim Cook advocating on behalf of Dreamers, Dick’s Sporting Goods CEO Ed Stack announcing an end to guns sales in his company’s stores following the Parkland High School shooting in February 2018, Siemens CEO Joe Kaeser denouncing the rhetoric of Germany’s new far right, or Merck CEO Ken Frazier leaving a White House advisory council in protest over President Trump’s Charlottesville remarks. Similarly, in the summer of 2020, dozens of leading US CEOs spoke out forcefully against police violence and racism following the murder of George Floyd and over one hundred called on President Trump later that year to support a peaceful transition of power following his election loss. The US Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v Wade was another watershed moment for CEO political activism, with many denouncing the ruling and pledging to ensure employees retained access to abortion care.

CEOs frequently invoke their personal morality and/or company values to explain why they weighed in on a particular issue. Reflecting on his denunciation of President Trump, Ken Frazier stated that “[i]t was my view that to not take a stand on this would be viewed as a tacit endorsement of what had happened and what was said. I think words have consequences, and I think actions have consequences. I just felt that as a matter of my own personal conscience, I could not remain [silent].” Similarly, in a court brief supporting Dreamers, Tim Cook wrote that “[w]e do so here to stress that not only does Apple care as a company, but we care as leaders, colleagues, and human beings. This is an issue we feel to our core.” Siemens’ Joe Kaeser explicitly referenced his company’s experience during the Nazi period to justify his outspokenness, saying that “[wh]at I want to document to the world is exactly that Siemens has learnt from its past — and others should too.”

This is not the first generation of corporate leaders with personal values, so something else must explain the growing political role of CEOs. What is different is the growing demand from stakeholders for CEO to signal their values and, by extension, that of their companies. Where does this demand come from? In sessions for CEOs and senior executives on this topic, I highlight four interacting drivers:

Political polarization. Western societies are experiencing extreme levels of political polarization. Research firm Edelman has found that two-thirds or more survey respondents in countries as diverse as Germany, the US, Nigeria, Sweden, Brazil, or the Netherlands believe their country is more divided than in the past. Across 27 countries, only 30 percent say they would help someone in need who strongly disagreed with them on a key issue. Divisions are particularly sharp in the US. In 2020, only 4 percent of Americans were married to a member of the other major political party. Whereas just 35 percent of Democrats viewed Republicans as immoral in 2016, 63 percent did in 2022. Republicans’ view of Democrats is even worse, with 72 percent viewing members of the other party as immoral compared to 47 percent six years earlier. As political scientist Liliana Mason has argued, in the US, politics has become identity and is increasingly viewed in zero-sum terms.

Big societal challenges. Societies are confronting major challenges, from climate change to inequities, artificial intelligence to mass migration. Extreme polarization means that governments are less able to tackle these as rival camps block one another. The US Congress passed just 24 bills that have become law in 2023, far less than in earlier periods of divided government. With governments increasingly unable or unwilling to lead on key issues, attention has shifted to the private sector. For instance, just days after President Trump withdrew the US from the Paris Climate Accords, Michael Bloomberg rallied CEOs, university presidents, mayors and some governors to sign a “We’re Still In” pledge. Similarly, in explaining his company’s decision to take unilateral action on guns, Dick’s CEO Ed Stack said, “Every business has to do what is right (…) Hopefully we can find legislative bodies to do something.”

Values-based brands. According to former Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz, “Mass advertising can help build brands, but authenticity is what makes them last. If people believe they share values with a company, they will stay loyal to the brand.” Many CEOs have heeded Schultz’s call to make values central to their brands, including through overtly political messages. When NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick led a polarizing protest against policy brutality, Nike made him a brand ambassador. Or consider how central women empowerment has become to the Barbie brand, clearly evidenced by the recent blockbuster movie. And then there is Patagonia, which once told customers “Don’t buy this jacket” and then proceeded to sue the Trump Administration over its environmental policies. Of course, value-based branding can backfire, as Bud Light experienced when conservatives called for a boycott over its association with transgender influencer Dylan Mulvaney. Even in the face of such backlash, however, rival beer CEO Dolf van den Brink of Heineken urged business leaders to “stand for their values.

Younger customers and employees. The expectations for companies and their leaders to signal their values is particularly high among Millennials and Gen Z. According to 5W, a public relations firm, 83 percent of customers aged 18 to 34 view it as important that companies they buy from align with their values, compared to 60 percent of those over 55. And whereas a mere 21 percent of Boomers say they “enjoy buying products that show off my social or political ideology or beliefs,” 62 percent of Millennials and Gen Z feel that way. Similarly, marketing firm Weber Shandwick has found that 34 percent of Millennial employees say their loyalty vis-à-vis their employer increases when the CEO takes a public position on a hotly debated issues versus just 14 percent of Boomers.

CEO political activism is a signaling device. In a more polarized, more divided world facing major issues, in which companies have made values more central to their brands, particularly younger customers and employees want to know where companies and their leaders stand on key issues that they themselves care about. Empirical research supports this. Aaron Chatterji and Michael Toffel have shown that CEO political activism strengthens customer purchase intent, though only among those who previously held views consistent with the CEO’s public position. Similarly, Adam Wowak, John Busenbark, and Donald Hambrick have found that a CEO’s public political position on marriage equality increases employee loyalty among those in agreement, while diminishing it for those with opposing views. Finally, a study by Young Hou and Christopher Poliquin has found that gun control advocacy by four prominent retail company CEOs temporarily diminished store attendance in conservative counties by 5 percent, while leaving it unchanged in liberal ones. In short, CEO political activism is not about changing stakeholder opinions. Rather, it is a way for CEOs to signal to key stakeholders which side they are on. This means that there are costs to taking a stand. Dick’s Ed Stack said that 65 employees “quit right away in protest, and more followed in later weeks” after the company announced an end to gun sales. The key question is the net effect. As Nike’s Phil Knight put it when the company embraced Colin Kaeperick: “It doesn’t matter how many people hate your brand as long as enough people love it.”

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine added geopolitics to the growing list of issues CEOs are expected to speak out on. When the war began, there was immediate pressure on Western CEOs to condemn Russia’s aggression and to cease operations there. While the extent of the “Russian business exodus” has been overstated, in part because the Kremlin has made leaving difficult, few prominent CEOs remained on the sidelines. Subsequent survey research by Edelman underscores the signaling effects of companies taking sides. Across thirteen leading economies, 31 percent of respondents said that knowing a company had withdrawn from Russia would increase their trust in it, while 38 percent said they would have less trust if it continued business as usual. Similarly, among employees who felt their company had met their expectations regarding the Russia-Ukraine conflict, 79 percent said they would remain loyal to the company and 80 percent would recommend it as an employer. In contrast, among employees who said their company had failed to meet their expectations regarding Russia-Ukraine, the corresponding figures were 55 percent and 54 percent. The same survey found that an astounding 59 percent of respondents believe that companies have “geopolitical responsibilities,” meaning obligations to “cultivate admiration for our country’s values” and to “punish countries that violate human rights and international law.” That is not much lower than the 77 percent who believe businesses have “societal responsibilities” in areas such as climate change, reducing poverty, and combating discrimination, issues many CEOs have long accepted as part of their job.

On October 7, 2023, Hamas attacked Israel. Once again, and predictably given the above data, stakeholders expected prominent CEOs to take a stand. Unlike the case of Ukraine, however, many Western CEOs experienced stakeholder backlash. As Fortune editor Alan Murray explained, “In the days after Oct. 7, some 150 companies issued statements condemning Hamas for its brutal attack on Israeli civilians. Now, many of those same companies are under pressure to issue equal condemnations of the bloodshed in Gaza. Companies that have said nothing are being attacked by both sides.” No wonder CEOs have been exasperated with many secretly longing for an earlier, easier time when delivering quarterly earnings and growth was enough. Beyond the immediate dilemma of navigating Middle East conflicts, however, this latest episode begs the question on the minds of many business leaders: when – and how – should we take a stand?

For Western CEOs, the major difference between Russia-Ukraine and Israel-Hamas is the degree of stakeholder unity. According to Pew, 70 percent of Americans viewed Russia as an enemy in March 2022, up from 41 percent before the invasion. Similarly, EU surveys found that 89 percent of Europeans citizens felt sympathy for Ukraine in April 2022. Taking a pro-Ukraine stance was not controversial. Indeed, it was expected. Contrast this with the deep divisions regarding the Middle East conflict. In May 2023, five months before Hamas’ attack, 29 percent of Americans said they supported Israel and 15 percent the Palestinians. In Europe, the picture was reversed, with more support for the Palestinians than for Israel. While Hamas’ attack pushed overall US support for Israel to 41 percent, a deep generational and ideological split became visible. Among those 18 to 29 years old, just 20 percent supported Israel following the attack while 29 percent supported the Palestinians. The average Fortune 500 CEO is 58 years old. In their age bracket of 45 to 64, 48 percent supported Israel and just 7 percent the Palestinians. In terms of ideology, Biden voters were roughly evenly split while three quarters of Trump voters supported Israel. The young-old, left-right split was similarly visible in Europe, only that the pro-Palestinian sentiment among younger and left-leaning respondents was even greater. Against this backdrop of division, and in particular the stark contrast between the views of the CEO generation and those of younger, more politically demanding stakeholders, the backlash against one-sided Hamas condemnation described by Murray should have been expected.

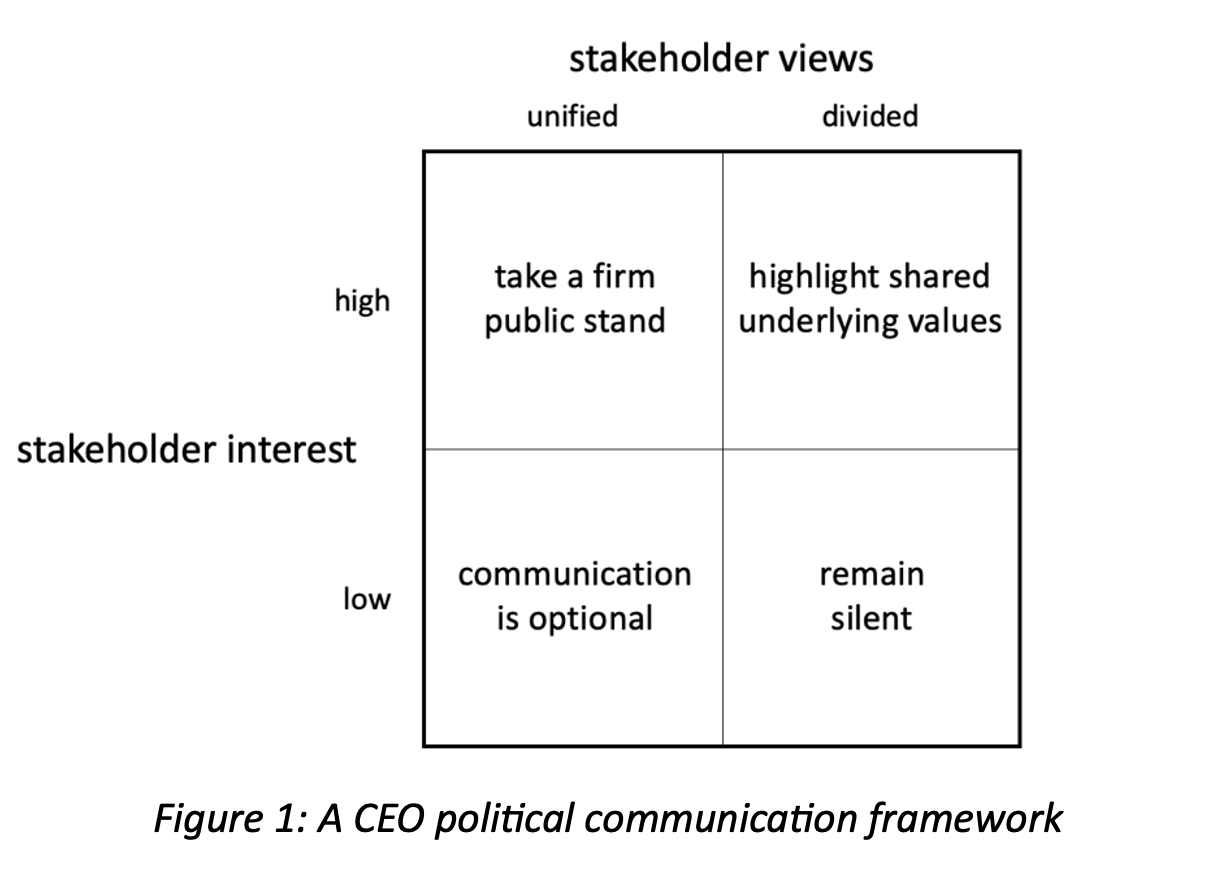

Figure 1: A CEO political communication framework

Figure 1 adds the degree of stakeholder unity to the salience dimension. In the age of stakeholder capitalism, if interest in an issue among key stakeholders is high, CEOs often have no choice but to be vocal. If CEOs have reason to believe that key constituencies broadly support their position, there is benefit in taking a firm stand, thus signaling company values and strengthening commitment. In contrast, when key stakeholder communities are deeply divided, CEOs risk worsening division by taking sides. In such situations, it is preferrable to elevate the discourse and highlight shared underlying values that most can agree on (see the sidebar for a GPT-4-generated example). To be sure, such an approach will not satisfy all. A good outcome would be support for the statement from the middle 60 percent of a bimodal distribution, with 20 percent on both ends of the spectrum finding it wanting. Lastly, must CEOs take a stand on every political issue or geopolitical conflict? Absolutely not. If interest among key stakeholders is low, it is perfectly fine and often preferrable for the CEO not to use their bully pulpit. A Polish CEO who condemns Russia’s war in neighboring Ukraine despite not previously speaking out against bloodshed in Yemen is not a hypocrite. She merely understands which conflict is more likely to unsettle her key constituencies.

Critics may view my framework as too instrumental. After all, CEO political activism should be about values and authenticity, not cold calculus. However, a fundamental responsibility of leaders is to bring people together. CEO political activism can be potent tool in this respect. Yet in the face of deep stakeholder division on a salient issue, this leadership imperative cautions against taking sides. Silence is not an option either since it leaves everyone guessing. Rather, the best approach is a statement that elevates and transcends, highlighting shared underlying values and trying to unite rather than exacerbating division.

To many CEOs, the lesson of the Israel-Hamas conflict is that it is impossible to get it right. Many think it would be better to put the genie of CEO political activism back in its bottle. That would be a mistake. Our fractured world needs the moral voice of CEOs. My work with executives and board members strongly suggests that CEOs can successfully navigate the confluence of geopolitical pressure and stakeholder scrutiny. The key to this is having one’s finger on the pulse of key stakeholders. Therefore, the lesson of October 7 and its aftermath is not that CEOs should remain silent, but that they must spend more time understanding the distribution of stakeholder views on key issues, particularly among younger and more politically demanding constituencies. Only then can CEOs use their voice in ways that unite.

Not sure what a message to employees focused on shared unifying values might look like in the case of Israel and Hamas? Here is what GPT-4 came up with after I fed it this article and gave it a straightforward two-part prompt*:

Dear Team Members,

In light of the recent outbreak of violence in the Middle East, I want to acknowledge the deep emotions and concerns that many of you have expressed. We recognize that our team is a tapestry of diverse backgrounds and beliefs, and the events unfolding affect each of us in different ways. It's important to remember that as a global family, our strength lies in our diversity and our ability to foster understanding and empathy among us.

As a company, we stand for peace, human rights, and the dignity of all individuals. We urge a de-escalation of violence and a return to dialogue as the pathway to peace. Our focus is to provide unwavering support to all our employees during this challenging time, including offering counseling services for those who need someone to talk to. We stand by our commitment to be an inclusive workplace where every individual feels respected and valued, regardless of their views on this issue.

Let us all reflect on what connects us: our shared humanity and the common values that unite us in our daily mission. I encourage everyone to engage with compassion, to listen with open minds, and to support each other as members of our global community. We will continue to monitor the situation and provide support to our team members and operations affected by this conflict.

With respect and hope for peace,

[Your Name]

CEO, [Your Company]

* Here is the two-part prompt. Prompt #1: “I have written an article for CEOs and would like you to apply some of the insights to give a hypothetical CEO some advice. Let me first paste the article.” Prompt #2: “Now assume I am the hypothetical CEO of a large multinational. I would like you to draft a two-paragraph message to my employees shortly after the outbreak of violence between Hamas and Israel. My employees are divided. Some are pro-Palestinian, and others are pro-Israeli. What should I say to my employees?”