California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier academic management journal published at UC Berkeley

by Umme Hani, Cary Cooper, Shahriar Akter, and Ananda Wickramasinghe

Image Credit | Umme Hani

Social banking has emerged as a feasible alternative suited to address persistent poverty by empowering women in ultra-poor settings through social entrepreneurship. It focuses on the social, environmental, and economic outcomes that stem from the establishment and maintenance of long-term relationships with social entrepreneurs (Bloom and Chatterji 2009). While traditional banks face significant difficulty in serving the poor, social ones provide ultra-poor women with access to finance that is crucial to escaping poverty. This article studied Grameen Bank, which is one of the largest social banks in the world, with more than 10.22 million customers from 81.678 rural villages in Bangladesh. Since October 2022, the bank has distributed around US$ 35,350.14 million to its poor customers, 97.25% of whom are women. As a pioneer of micro-credit programmes in the world, the Grameen Bank as a social bank has empowered millions of vulnerable women in Bangladesh, and its business model is currently operating in 50 countries across the world with transformative social impact (Rangan & Gregg 2019).

“How Social Entrepreneurs Zig-Zag Their Way to Impact at Scale” V. Kasturi Rangan & Tricia Gregg

“Scaling Social Entrepreneurial Impact” by Paul N. Bloom & Aaron K. Chatterji

Although women’s empowerment is at the core of the social banking business model, the relationship pathways ultra-poor women travel in their entrepreneurship and empowerment journeys remain unexplored. On the one hand, the micro-credit program of this business model has emerged as a proven alternative to tackle the grand challenge of poverty. On the other hand, it is far from perfect, as ultra-poor women are unable to think clearly, make good decisions, maintain solid relationships, or have much self-confidence due to chronic poverty.

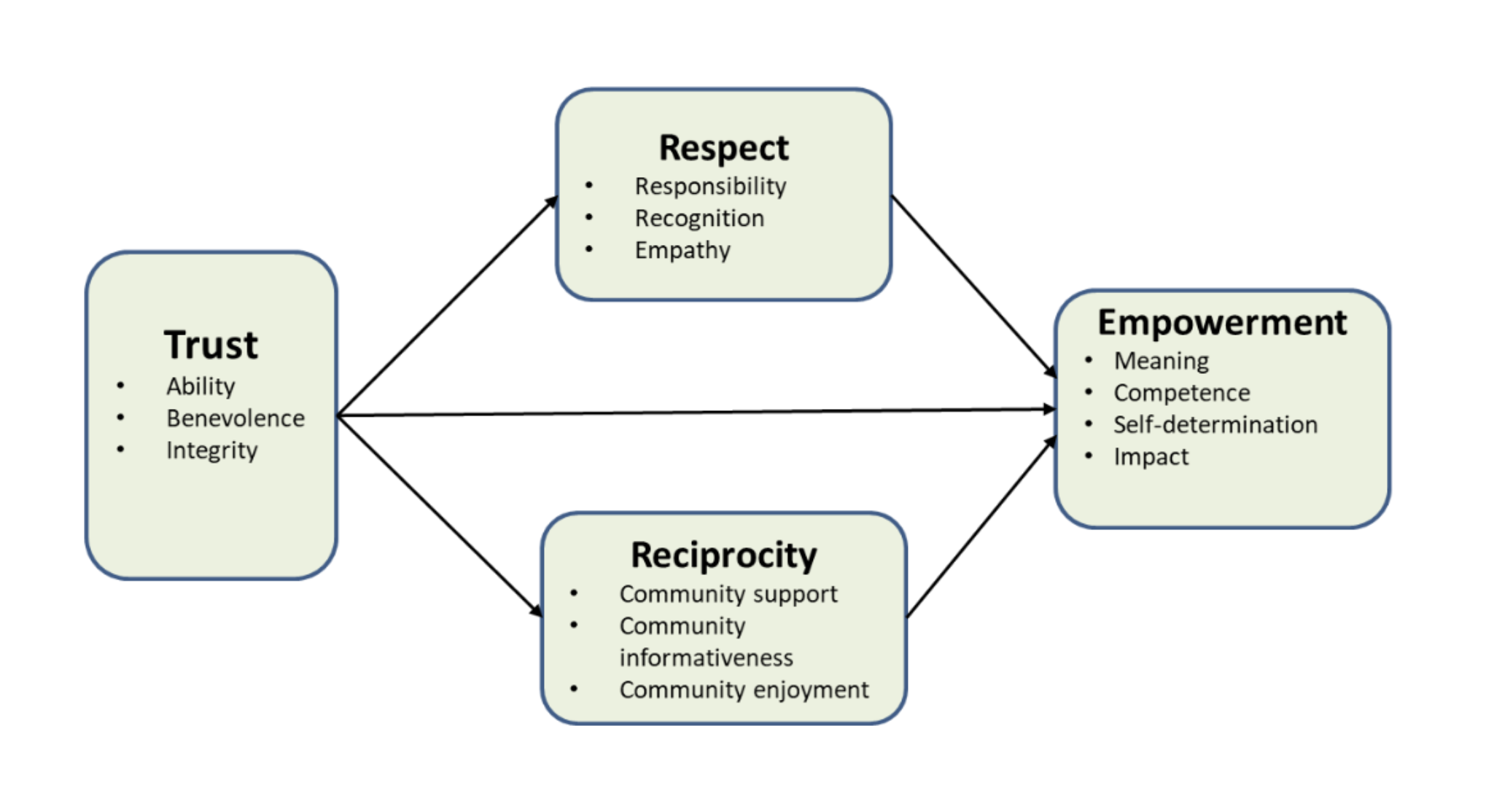

How does trust-based relationship quality psychologically empower women entrepreneurs in ultra-poor markets? Does perceived trust influence respect and reciprocity? How can social banks figure out how best to apply it? To address this challenge, this article draws on our investigation consisting of studies on Grameen Bank’s projects in Bangladesh between 2018-2023, thirty in-depth interviews, two focus group discussions and 807 surveys of Grameen entrepreneurs with at least 20 years of business relationships with the bank and, finally, an interview with the founder of Grameen Bank Nobel Peace Laureate Muhammad Yunus. Thus, this paper highlights how, in resource-poor settings, trust builds empowerment through respect and reciprocity. Specifically, how trust-based relationship quality contributes to lifting women out of poverty by influencing the degree of perceived respect and reciprocal exchanges.

We have observed this nomological network again and again from customers’ (i.e., ultra-poor women entrepreneurs’) perspectives and have evidenced how a transformative social bank (i.e., Grameen Bank in Bangladesh) leverages it to psychologically empower ultra-poor women entrepreneurs across the world.

Let’s look at these three relationship quality dimensions more closely.

Figure 1: Trust-based relationship quality and empowerment in social banking

We identify perceived trust as the building block of Grameen Bank’s empowerment of its ultra-poor women entrepreneurs, as Yunus states (1998, p.21), “relationships are to be with people, not with papers. They build up a human relationship based on trust.” Trust refers to the expectations, beliefs, and sentiments elicited in ultra-poor women entrepreneurs by Grameen Bank’s ability, benevolence, and integrity. Ability denotes the skills, characteristics, and competencies the bank deploys to suit the distinct needs of ultra-poor customers. Extremely poor women who are also business owners need customized assistance because they are constantly confronted with new challenges linked to poverty, violence, and uncertainty. Therefore, providing customized investment advice suited to an entrepreneur’s unique needs is considered the bank’s ability. Benevolence refers to the extent of Grameen bank’s desire to do good under changing circumstances. In business relationships, perceived benevolence—as a synonym for openness, support, loyalty, and care (Colquitt, 2007)—which increases loyalty among business partners. Grameen Bank is viewed as benevolent as it is prepared to expend extra efforts when unforeseen issues arise. Specifically, women in extremely disadvantaged settings are disproportionately affected by abrupt social or environmental restrictions as well as by family violence (Dufflo, 2009). Finally,the integrity of Grameen Bank plays an instrumental role as a social bank as it possesses the skills required to carry out its job reliably and effectively. It is the extent to which the bank is perceived to espouse moral and ethical principles. For instance, ultra-poor women in Bangladesh who have low literacy, are not tied to Grameen Bank by formal contracts. Thus, performing their job reliably (e.g., accurately complying with the transaction) is perceived as an indicator of integrity. If poor women entrepreneurs find out that a social bank has a low moral character, they typically perceive it as being of low value or worth to them. While trust signals the judgments or perceptions of a social bank’s credibility, respect is built on a foundation of trust—signifies the ultra-poor women entrepreneur’s perceptions of their own worth (Ramarajan et al., 2008). Therefore, respect is not something that people intuitively assess on their own; rather, it is a judgment made on the basis of the way a social bank trusts its ultra-poor customers.

Respecting a person involves paying close attention to and taking him/her seriously or, valuing an individual’s perspective. It describes how a person’s self (his/her identity and ability to function in the environment) reflects the approval and recognition received from others. Such recognition of one’s existence promotes the positive self-perceptions to which all humans are deemed to be entitled. Therefore, any respect received validates an individual’s value as a human being. Although respect has been seen as a fundamental human right and obligation, most poor people are deprived of it. The sense of neglect and disrespect found in the context of ultra-poor markets is brought into focus by the following quotation from Chakravarti (2006, p.366): “Poverty is humiliation, the sense of being dependent on them, and of being forced to accept rudeness, insults, and indifference when we seek help.” Respect is a powerful social dimension that symbolizes the acceptance and acknowledgement of a person living in extreme poverty. It is worth noting that a respectful attitude acknowledges both the esteem and dignity of a person, which helps promote positive behaviours. In relation to social banking, respect influences the quality of relationships between banks and ultra-poor women entrepreneurs. Thus, the respect perceived by the latter influences their participation in social banking and empowerment. In this context, respect refers to how the sense of self of an ultra-poor woman entrepreneur (her sense of who she is and how she fits into her surroundings) is improved as a result of the bank’s approval and recognition. We identify three subdimensions of respect in social banking: recognition, responsibility, and empathy. Thus, as a behaviour, a social bank’s respect is reciprocated by ultra-poor women entrepreneurs by giving their best to fight poverty and sustaining their ventures.

The ultra-poor women entrepreneurs’ perceived trust in Grameen Bank influences their perceived norms of reciprocity in business relationships. Reciprocity refers to a social bank’s hosted reciprocity norms, in which reciprocity is reflected through perceived enjoyment, community support and informativeness. Grameen Bank hosts reciprocity norms based on the expectation that ultra-poor women entrepreneurs will address each other’s problems collaboratively. Living on the edge of society, the poor’s only possible resource to survive in a brutal and unpredictable world is their capacity for reciprocity. Based on this capacity of ultra-poor women entrepreneurs, Grameen Bank in Bangladesh establishes high-quality relationships with trustworthy attitudes, which thus constitute ‘cognitive relationships’, such as norms of reciprocity among ultra-poor women entrepreneurs, whereby they mutually support each other. We found that each component of trust contributes additively to the perceived norm of reciprocity among ultra-poor women entrepreneurs and protects them from chronic stress, concern, and uncertainty.

We define empowerment as the increase in the entrepreneurs’ perceptions of their abilities to cope with the challenges linked to running their businesses (Spreitzer, 1995). Extremely poor women who start ventures may worry about lacking the means and the coping mechanisms necessary to meet the challenges posed by poverty. The damaging effects of poverty can be mitigated by developing a strong sense of trust; thus, those relationship factors that promote a sense of control in the face of challenges may reduce any feelings of helplessness (Brockner et al., 1998). The ultra-poor women entrepreneurs’ perceptions that a social bank has their best interests at heart results in less staggering judgments because it elicits in them the belief that such a bank is working for them. Those entrepreneurs who consider a social bank to be competent, benevolent, and honest may also appraise their own vulnerability as less threatening because they perceive that such a bank will be on their side during challenging situations. Similarly, when ultra-poor women—who are deprived of every single human right they deserve—perceive the empathic attitude (e.g., by obtaining a badly needed loan or relief from one in an unexpected situation) of a social bank, their self-worth is enhanced, their vulnerability is reduced, and their perceived psychological empowerment is thus improved. Also, in the absence of resources, reciprocity, resource sharing, and extended kinship enable disadvantaged groups to thrive in such markets. Overall, the psychological empowerment of women entrepreneurs is a type of intrinsic desire to engage in activities that consists of four cognitive dimensions: meaning, competence, self-determination, and impact (Spreitzer, 1995). Meaning refers to the sense that the work carried out by ultra-poor women entrepreneurs is personally significant. Competence refers to the degree of confidence that ultra-poor women are capable of successfully completing a task. Self-determination refers to the independence in choosing how to carry out work activities. Finally, impact describes the extent to which an ultra-poor business owner believes that her actions have an effect.

The study provides several practical guidelines regarding relationship dynamics and women empowerment in ultra-poor markets. To begin with, a social bank could create, organize, and scale up its activities, focussing on relationship quality. First, in order to better grasp relationship dynamics, social bank managers should spend greater efforts in understanding local socio-economic matters, subcultures, consumption habits, product developments, and marketing operations in order to break the vicious cycle of poverty and empower the ultra-poor women through small businesses. Second, trust perceived by ultra-poor women entrepreneurs in a social bank can significantly enhance perceived respect, which motivates them to continue their exchange relationships. This is a valuable insight for social banks to design responsible and empathetic offerings suited to navigate any uncertainties. Such a business model may collapse in the presence of a relational conflict or if the bank fails to embrace the ideas and feelings of ultra-poor women in relation to continuing in their entrepreneurial ventures. Third, having differentiated the impact of trust from that of respect, we urge managers to design customer support groups for conflict resolution, emotional assistance, and approval. Managers can learn more about the struggles, lives, and lived experiences of women entrepreneurs. Capitalizing on our findings, social banks can promote women’s empowerment by communicating the meaning of their ventures to the community, recognizing their long-neglected competence to run a business, identifying their rock-solid self-determination to stand on their own feet and highlighting the impact of their work in unleashing powerful forces for social development.

Bloom, P.N. and Chatterji, A.K., 2009. Scaling social entrepreneurial impact. California Management Review, 51(3), pp.114-133.

Brockner, J., Heuer, L., Siegel, P. A., Wiesenfeld, B., Martin, C., Grover, S., Reed, T., and Bjorgvinsson, S., 1998. The moderating effect of self-esteem in reaction to voice: Converging evidence from five studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(2), p.394.

Chakravarti, D., 2006. Voices unheard: the psychology of consumption in poverty and development. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16(4), pp.363-376.

Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., LePine, J. A., 2007. Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: A meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, p.909.

Ramarajan, L., Barsade, S. G. and Burack, O. R., 2008. The influence of organizational respect on emotional exhaustion in the human services. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(1), pp.4-18.

Rangan, V.K. and Gregg, T., 2019. How social entrepreneurs zig-zag their way to impact at scale. California Management Review, 62(1), pp.53-76.

Spreitzer, G. M., 1995. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), pp.1442-1465.