California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier professional management journal for practitioners published at UC Berkeley Haas School of Business.

by Herman Vantrappen and Frederic Wirtz

Image Credit | Abul

Executives who believe that their company’s organization never needs redesigning are few and far between: Since an organization is a means to achieve business ends, and since these ends do change over time, the organization design is bound to evolve as well. For example, structural contingency theory opposes the notion that there is one best structural form; instead it states that the most appropriate structural form depends on the specific set of conditions under which the firm operates.1 Hence, when the firm’s external context changes, its organization may have to change as well.

“Ambidextrous Organizations: Managing Evolutionary and Revolutionary Change” M.L. Tushman and C.A. O’Reilly, California Management Review Vol. 38, No. 4 (1996): 8-29.

So, the need for organizational design changes is not an issue. The real issue is about the optimal pace of change. It breaks down into three sub-questions whenever the concrete need for an organizational redesign emerges:

There is not a simple algorithm that provides the answer for all particular situations that executives face. Fortunately most executives do not need such an algorithm: They sense quite well what pace of change is the most suitable for any particular situation. What they may lack, however, are metaphors and visuals for convincing stakeholders about the chosen pace of change. Sticky metaphors in particular have proven to be powerful.2 In this article we will share a menu of metaphors and visuals that we have borrowed and adapted or developed through our long advisory work with executives at organizations in a wide variety of situations.

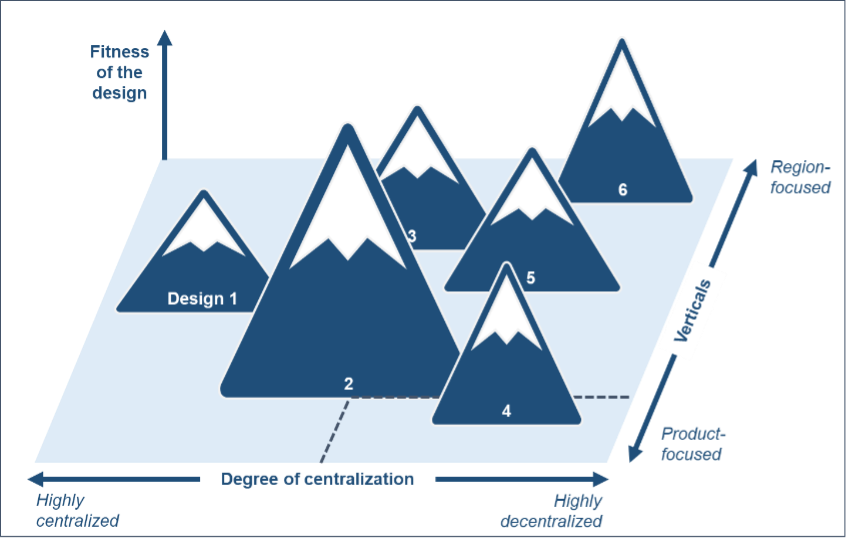

Daniel Levinthal introduced the “rugged landscapes” metaphor in the context of organizational design.3 Imagine a multi-dimensional map in which each dimension corresponds with one possible design feature, for each of which one can choose a specific position along a scale. For example, the company’s degree of centralization could be one dimension, and its scale could range from highly centralized to highly decentralized. Each combination of chosen positions across the dimensions then corresponds with a different location on the map, and represents a particular organization design. Finally, one adds a dimension indicating the fitness level of the designs.

Lest you get a headache from trying to visualize the above abstraction, and for the sake of illustration, let’s limit the number of features to two. One then sees a varied 3D-landscape consisting of lowlands and mountains, with the mountain peaks pointing to alternative designs that fit well with the company’s needs. Exhibit 1 shows an example where design 2, which features a medium level of centralization and a rather strong product focus, appears to be the best fitting design. Depending on its starting position in the landscape, the company may of course discover and go for a different peak.

Exhibit 1: A landscape of alternative organization designs

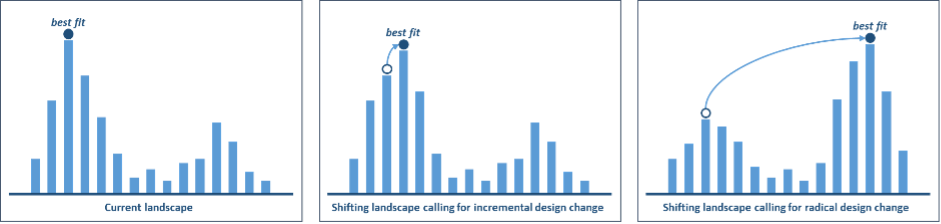

This is a genuinely fabulous metaphor. But even with only two design features, it takes quite some 3D-drawing skills to use the metaphor on the fly. That is why we like to convert it into the simple visual shown in Exhibit 2, whereby the positions along the horizontal axis correspond with alternative designs, and the height of the bar indicates the fit of a particular design for the company.

Exhibit 2: Fit of alternative organization designs

You can use this visual to address questions about the pace of change (see Exhibit 3). For example, if you want to talk about incremental change, you could point to “seismic vibrations”: factors that are leading to slight variations in the height of some adjacent bars, thus the need for the organization design to evolve, a bit toward the left or the right. If you want to talk about radical change, you could point to a “tectonic shift” and the risk of “mountain collapse”: factors that are leading to a drastic shrinkage of the bars at one’s current location and their rise at a distant location, thus the need for migration.

Exhibit 3: Visualizing incremental and radical change

To address questions about the magnitude and/or frequency of change, you can also use a grid combining these two variables (see Exhibit 4). The zone of sensible approaches in most situations stretches from the upper right quadrant (radical + rarely) to the lower left (incremental + continually).

A radical design change may be needed at some point, but should not be undertaken lightly. Much as you may aspire rupture with the current way of working, you cannot afford disruption: You have to safeguard the ongoing business, which critically depends on the continuity of your people, processes and networks. Continual radical change leads to exhaustion (“We have barely gotten used to the new way of working, and they’ve changed their mind again.”)

Conversely, frequent incremental changes are unavoidable or even desirable: You have to align with external developments and offset design imperfections. Forsaking regular incremental change leads to disfunction and instills a culture of abdication (“I have given up trying to shake up things in this place – nothing ever changes.”)

Exhibit 4: Visualizing the varying pace of change

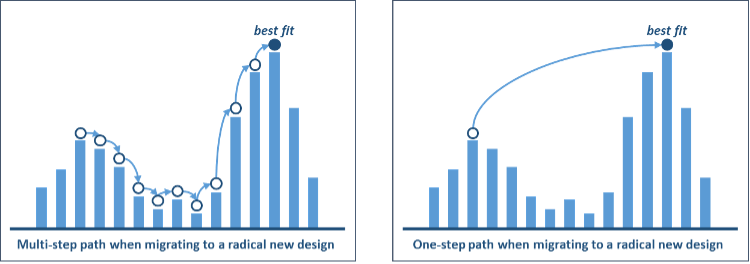

To clarify the path to follow when making a radical organization design change, you can also use the rugged landscape visual (see Exhibit 5). In the case of radical change, the option of a long trek – descending from your current peak and climbing toward the targeted peak – doesn’t appear wise: People may constantly look backward while going downhill (possibly not all at the same speed), and then grumble while sweating their way uphill; furthermore, by the time they arrive at destination, the landscape may have shifted again. Therefore, a direct helicopter airlift from the current to the target peak may be the better option.

Exhibit 5: Visualizing the paths toward a radical new design

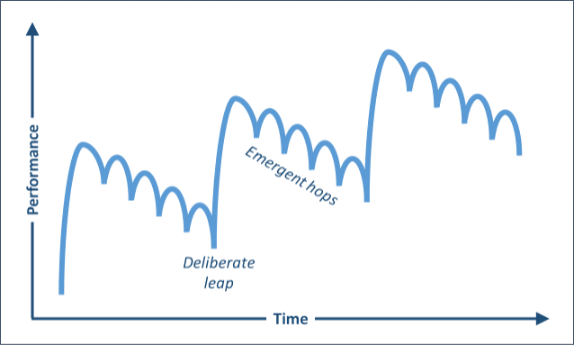

The magnitude-frequency grid also implies that companies tend to go through cycles consisting of an occasional radical design change followed by a series of incremental changes. We call this the leap-and-hops pattern: Senior management purposefully decides on a major rearrangement of the organization (“deliberate leap”), after which a series of adjustments (“emergent hops”) are made to course-correct and compensate for the inevitable imperfections of the design (see Exhibit 6).4 A leap may be triggered by a major strategic event such as a change of business model or a merger. It may also be triggered by the finding that the accumulation of past hops has made the organization overly complex or unwieldy. This pattern is totally normal, since the company’s environment changes all the time and the perfect design is elusive. You can use the visual, for example, to characterize your current redesign either as a hop or a leap, and compare it to previous redesigns with which people can associate. Michael Tushman and Charles O’Reilly observed the same pattern of “periods of incremental change punctuated by discontinuous or revolutionary change”, which led to the concept of the “ambidextrous organization”.5

Exhibit 6: A pattern of deliberate leaps and emergent hops

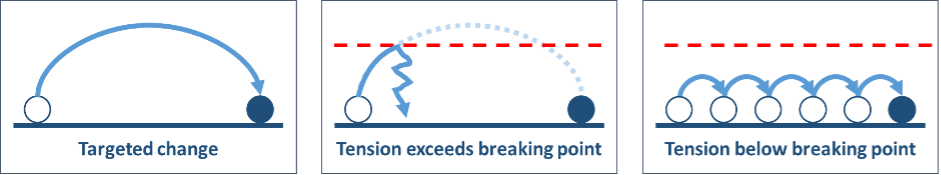

When advocating incremental change, the question about the magnitude of the increments pops up immediately. One can easily visualize the situation where the increment is too large: When the applied tension exceeds the breaking point, the landing may be painful and the change will not materialize; therefore, it is safer to progress in smaller increments (see Exhibit 7).

Exhibit 7: Visualizing change staying below breaking point

But going for too small increments carries risks as well. To demonstrate that risk, we have adapted the concept of “dominant logic”, as explained by Richard Bettis and C.K. Prahalad.6 They describe it as a logic that invisibly permeates the company, with a pervasive influence on how people undertake to solve problems. The logic predisposes them to certain types of solutions, as if it were a genetic factor. It makes them stay close to familiar organization designs and an equilibrium that feels comfortable. To make a decisive shift toward a new equilibrium, the company should unlearn its old dominant logic and move substantially away from its original equilibrium. The foregoing means that change is to be visualized not as a rectilinear but a bumpy path, and the increments have to be sufficiently large to avoid rollback (see Exhibit 8).

Exhibit 8: Visualizing change along a bumpy path

So far we have talked about the magnitude (incremental vs. radical) and frequency (continually vs. rarely) of change. To address the third aspect of the pace of change, namely its timing (proactive vs. reactive), the thermostat metaphor is quite powerful.7 A thermostat regulates room temperature by comparing the actual temperature with the setpoint, say, 20°C, and then switching a heating device on or off. In order to prevent excessive on-off cycling of the device – which increases wear and tear – the thermostat is designed to exhibit what physicists call hysteresis: It only switches the device on when the temperature has dropped to 19°C, and only switches it off when the temperature has reached 21°C.

You can apply the notion of hysteresis also to organizational redesign (see Exhibit 9). Imagine that you expect an important development in your company’s business context from A to B (e.g., an updated strategy) and sense that your organization design will have to change accordingly from X to Y. You may nevertheless wait with the organizational redesign from X to Y until the business context has changed from A to B conclusively. The drawback is that the ultimate design change may be overdue and require a scramble to catch up, leading to an opportunity cost, as indicated by the shaded area. This reactive approach shows up as organizational “hysteresis”.

The opposite alternative is to start the organizational redesign well ahead of the anticipated change of the business context. The drawback is that the design change may be premature and create confusion or even chaos. The cost of such disarray may be high, as indicated by the shaded area. This proactive approach shows up as “inverse hysteresis”.

To minimize the opportunity and disarray cost, yet without having your company undergo a constant flux of change, you may consider a mixed reactive-proactive approach.

Exhibit 9: Hysteresis in organizational redesign

You should look at the above collection of metaphors and visualizations as a menu from which to pick and choose. Depending on your specific circumstances and personal appetite, you may prefer the one to the other. For example, if someone questions the need for a redesign (“Why change – our current design is serving us well, after all?”), you may sketch and talk about a shift in the rugged landscape. If someone is adamant about imitating your competitor’s organization model (“Doesn’t their success speak for itself?!”), you may point out that the competitor went for a different and distant mountain peak because of their different origin and development path. If someone cynically moans about a redesign decision (“Oh no, here we go again …”), you may encourage them to think about the nuances of hops and leaps. If someone advocates extreme care when starting a redesign (“All fine, but above all let’s not rock the boat”), you may draw a bumpy road and remind them that smooth progress requires jumping. Generally, when preparing your narrative about the organizational redesign, remember the adage “A picture is worth a thousand words”. An apt metaphor makes it stick.

H. Mintzberg, “The Structuring of Organizations” (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1979).

C. Gallo, “How Great Leaders Communicate,” Harvard Business Review, November 23, 2022.

D. A. Levinthal, “Adaptation on Rugged Landscapes,” Management Science 43, no. 7 (1997): 934-950.

H. Vantrappen and F. Wirtz, “A Smarter Process for Managing and Explaining Organization Design Change,” Strategy & Leadership 46, no. 5 (2018): 36-43.

M.L. Tushman and C.A. O’Reilly, “Ambidextrous Organizations: Managing Evolutionary and Revolutionary Change,” California Management Review 38, no. 4 (1996): 8-29.

R. A. Bettis and C. K. Prahalad, “The Dominant Logic: Retrospective and Extension,” Strategic Management Journal 16, no. 1 (1995): 5-14.

H. Vantrappen and F. Wirtz, “The Organization Design Guide: A Pragmatic Framework for Thoughtful, Efficient and Successful Redesigns” (New York: Routledge, 2024).