California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier professional management journal for practitioners published at UC Berkeley Haas School of Business.

by Francis D. Kim and Rajendra Srivastava

Image Credit | printartist

Deep tech projects, based on breakthrough scientific or engineering innovations and new ways of problem-solving, are riddled with uncertainties as both opportunity and challenge. When technological innovations occur and are well-received by customers and investors, deep tech projects can be highly profitable, as seen in the rise of the so-called “Magnificent Seven” deep tech companies during recent years. On the other hand, enormous R&D spending does not always lead to technological breakthroughs, and deep tech projects are often met with skepticism and slow recognition on the market.

To Be or Not to Be: Will Virtual Worlds and the Metaverse Gain Lasting Traction?. Andreas Kaplan and Michael Haenlein. 66/4 (2024).

How Incumbent Firms Respond to Emerging Technologies: Comparing Supply-Side and Demand-Side Effects. Julian Birkinshaw. 66/1 (2023).

Given technological and market uncertainties with deep tech projects, how can investors differentiate among varieties of deep tech projects and select potentially more successful and investment-worthy ones? Furthermore, how can project leaders calibrate strategies of communicating their innovations with customers and investors according to deep tech project types? For instance, how can you tell the differences among various projects of Apple, Tesla, Meta, and OpenAI, beyond lumping them together under the generic rubric “deep tech”? Also, how can you systematically assess why, say, Elon Musk was more successful in managing uncertainties with electric vehicle (EV) technology than Mark Zuckerberg with the metaverse or Tim Cook with the self-driving car?

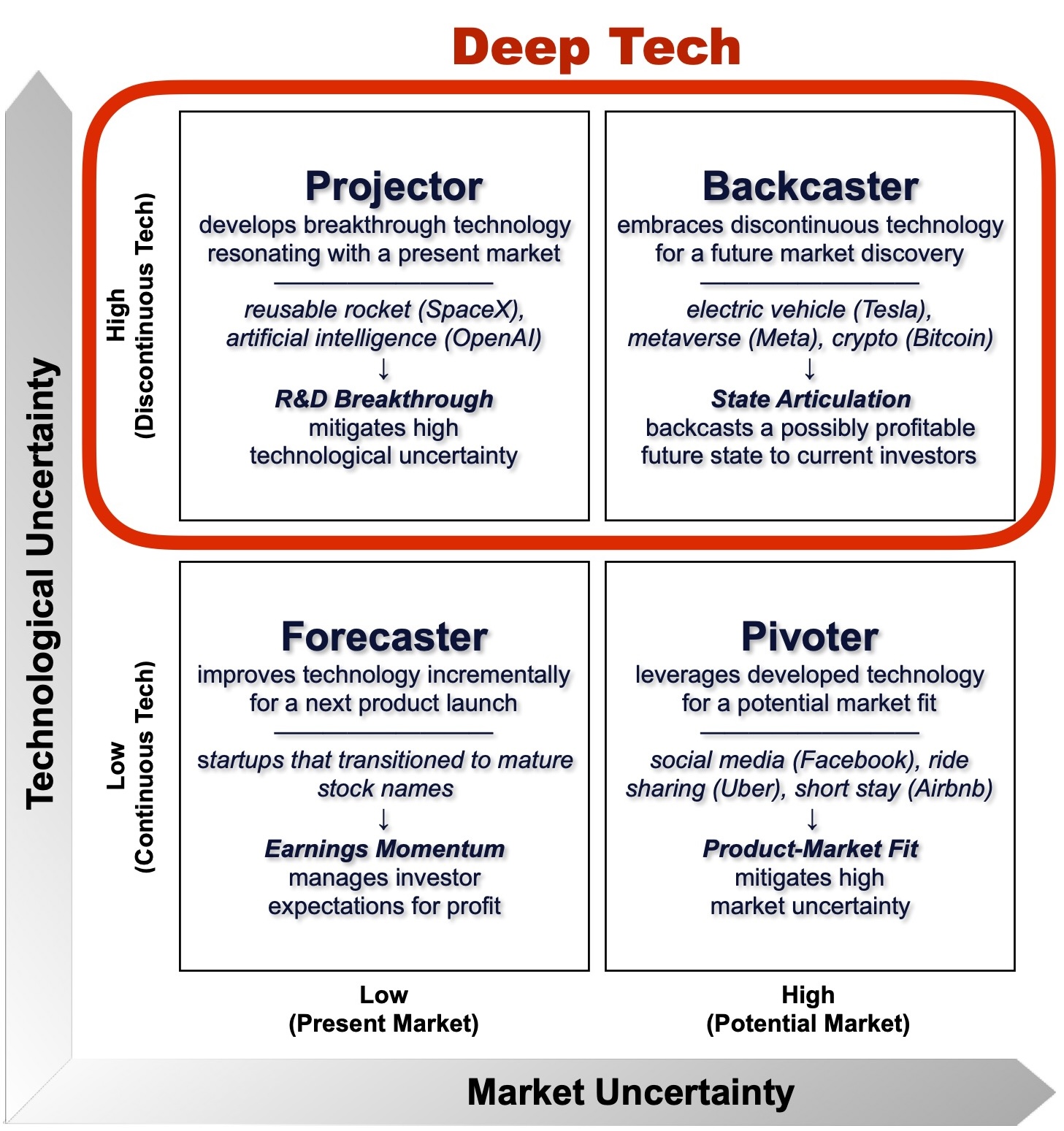

This article proposes a novel typology of deep tech projects that offers insights into these questions. Building on the literature’s emphasis on uncertainty in entrepreneurship,1,2,3 we map out 4 types of the entire tech innovations (of which deep tech projects are a part) based on two sources of uncertainty: Is technological uncertainty high (or low) because a given deep tech project uses discontinuous (or continuous) technology? and Is market uncertainty high (or low) because the deep tech project targets a potential (or present) market?

4 Types of Tech Innovations

Pivoting Innovation. Tech innovations that couple existing technology with a potential market discovery fall on this type. Pivoters repurpose and incrementally improve existing technologies without relying on resource-intensive technological breakthroughs, thereby minimizing technological uncertainty. Instead, they create values by discovering a potential market of many customers and seeking feedback and learning from the market to cope with high market uncertainty.4 Here, project leaders need to focus on a product-market fit and to show evidence that their product meets a need in the potentially ever-increasing market. This is also the information that investors are looking for.

Facebook is a good example of pivoting innovation. Launching it from a college dorm room in 2004, Facebook’s founders capitalized on the extant widespread use of computers and the internet (that is, continuous technology that college students could comfortably tinker with). Its success mainly came from a clever marketing strategy that satisfied a great pool of potential users, by, for example, simplifying the registration and ID verification processes.

Forecasting Innovation. This innovation type is characterized by low technological and low market uncertainties because it utilizes existing or incrementally-updated technologies for a present (that is, existing) market.5 Once startups have become successfully established and transitioned to familiar stock names, they often concentrate on forecasting innovation. Here, project leaders emphasize forecasts of their earnings momentum relative to that of peers within the established sector in communicating with investors.

Projecting Innovation. In our typology, projecting and backcasting innovations capture deep tech projects because both face high technological uncertainty arising from enormous R&D spending and the use of breakthrough or discontinuous technology that can disrupt the socioeconomic and cultural status-quo.5 Yet, they differ from each other in terms of the level of market uncertainty they need to cope with.

Projectors are characterized by low market uncertainty because, while they develop breakthrough technologies, their innovations, upon available, will likely resonate with the present market of customers who will find their immediate utility, such as a cure for Alzheimer’s disease. SpaceX’s reusable rocket technology and OpenAI’s ChatGPT are real-life examples of projecting innovation. Both shocked the public with their radical innovations and problem solutions, yet were soon to become commercialized and profitable. Here, project leaders rely on R&D breakthroughs to communicate with investors because these breakthroughs help defuse high technological uncertainty associated with projecting innovation.

Backcasting Innovation. Backcasting innovation is the second type of deep tech projects that features high market uncertainty as well as high technological uncertainty. This innovation type requires project leaders to imagine the future regarding how potential customers would embrace and use an entirely new, radical product, and to work backward to enable such applications.6

In our view, backcasting innovation is the least recognized type in the literature, often conflated with projecting or pivoting innovation. However, it should be regarded as a distinct type of deep tech projects. To begin with, backcasters are similar to projectors in that both need R&D breakthroughs to mitigate high technological uncertainty associated with use of discontinuous technology. However, unlike the latter, backcasters face high market uncertainty because their technology, even if developed, may not find a clear fit within the present market, as seen in customers’ confusion about what to do with bitcoin and blockchain technology when it was released for the first time in 2009. Also, while both backcasters and pivoters face high market uncertainty, backcasters’ reliance on discontinuous technology makes their project outcome and market success far more open-ended and unpredictable.

In our recent work, we have demonstrated that Tesla since 2004 under Elon Musk’s leadership exemplifies how backcasting innovation could be successful in managing both high technological and high market uncertainties. Specifically, Musk succeeded in mitigating market uncertainty associated with Tesla’s backcasting innovation, by convincing the public and the American government about a climate change-impacted future world and EV technology as a viable solution.6 Also, Tesla effectively addressed technological uncertainty by continuously improving product capabilities (such as driving range and battery life) while pursuing experience-based cost reductions.6 Here, project leaders need to gain investors’ confidence by effectively visualizing expectations of the future and their capability to meet challenges and opportunities in the present through radical innovations.

We further demonstrate our typology’s utility by focusing on the heretofore understudied backacasting innovation, and by analyzing the Meta debacle in 2021 and the Apple car demise in 2024.

The Meta Debacle in 2021 as a Tale of a Backcaster Who Acted Like a Projector. As explained above, Facebook, founded by Mark Zuckerberg and colleagues in 2004, started as a typical pivoter because it needed no breakthrough technology. However, when Zuckerberg attempted to rebrand Facebook into Meta in 2021, it was criticized for lacking substance in the company’s name change. Although we do not wish to minimize the unavailability of metaverse technology as a source of Facebook’s problem,7 we argue that the Meta debacle was a consequence of Facebook project leader Zuckerberg’s misidentifying his company’s essentially backcasting innovation as a projecting innovation and hence failing to mitigate high market uncertainty in communicating with investors.

In 2021, Zuckerberg introduced the metaverse as “a logical evolution” and “the next generation of the internet,” emphasizing its relevance to the present market of customers as if the metaverse were a projecting innovation. Of course, the pitch was undermined by the lack of sufficient R&D evidence, leading investors to lose confidence in Meta’s proposal. In our view, however, the Meta debacle could not be solely attributed to metaverse technology’s underdevelopment, that is, high technological uncertainty. Equally important was Meta CEO Zuckerberg’s inability to convince customers to imagine themselves as beneficiaries of the metaverse’s more immersive, 3D experience in everyday life through use cases that would facilitate both product and market development. In consequence, while Meta lost $50 billion in R&D, its loss in market value amounted to two-thirds of $1 trillion throughout 2022. The Meta meltdown continued until Zuckerberg abandoned the metaverse and jumped on the artificial intelligence bandwagon in early 2023.

The Apple Car Demise in 2024 as a Tale of a Backcaster Who Acted Like a Forecaster. In 2014, Apple CEO Tim Cook launched a new project to develop and design a self-driving electric car, codenamed “Project Titan.” However, in February 2024, after a decade-long R&D effort, Cook abandoned the project completely. We claim that the Apple car demise was a result of Cook’s approaching this intrinsically backcasting innovation as if Apple were dealing with a forecasting innovation and thus failing to resolve high technological uncertainty.

Apple’s “Titanic disaster” was driven by both high market and high technological uncertainties. Although Apple conceived of its new car as basically a luxury living room on wheels with no steering wheel and no windshield, it was unclear whether customers would actually want such “a product that didn’t look and feel like a car” without resistance.8 Yet, while the challenge of a future market discovery was of certain importance, how Apple approached high technological uncertainty was crucial. By the time Project Titan took off, Apple had already established itself as a tech giant focusing on earnings momentum through product launches and updates. In our view, this forecaster mindset appeared to shape the way Cook and executives tackled uncertainties. They were “concerned about the vehicle being able to provide the profit margins that Apple typically enjoys on its products,” especially given the car industry’s low margins and no guaranteed return from enormous R&D spending.8 More generally, historically Apple has been a “design” and “branding” company and, compared with other tech giants, been very conservative on R&D spending, committing only 4-5% of its revenue to R&D in comparison with its peers’ 10-15%. As such, Apple has tended to concentrate on developing market acceptance rather than technological prowess and breakthroughs.

Also, Apple’s commitment to the self-driving electric car as a backcasting innovation was weakened by the worry that Project Titan might negatively affect Apple’s earnings momentum by draining engineers from Apple’s other projects like Apple Watch and iPhone and interfering with their scheduled release.8 Ultimately, although Apple was spending $10 billion and 2,000 employees of its Special Projects Group were working on the project for 10 years, the company ended up failing to develop a fully autonomous driving system required of the Apple car. That the EV industry became far less compelling and attractive by early 2024 delivered a coup de grace to the faltering Apple car project.

Both the Meta debacle and the Apple car demise underscore the real risk of backcasting innovation characterized by the double layers of high technological and high market uncertainties. They are in contrast with Tesla that, as we have explained, showcases successful management of both technological and market uncertainties, with its market capitalization during recent years surpassing that of top rival carmakers combined. Even so, pioneering backcasters’ success like Tesla’s poses its own challenge because followers such as BYD can emulate and outperform the first movers through more efficient and effective entrepreneurial strategies.

If you as a project leader or an investor are involved in deep tech projects, you should understand their inner differences and associated uncertainties in a systematic and nuanced way. This article offers you an explanatory typology of tech innovations that can serve as a useful guideline and assessment tool.