California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier academic management journal published at UC Berkeley

by Craig Hirst and Gary Burnand

Image Credit | Maximusdn

Across the globe, businesses are challenged to address the growing environmental crisis. At the same time, the records for carbon emissions, global temperatures, sea levels, polar ice loss, and ocean warming, continue to be broken1. The analogy of the super-tanker not turning, is increasingly applicable to climate change, in fact by most metrics, it is speeding up and way off course. Things must change. Enabling that change however, is proving problematic, with many businesses sleepwalking into climate disaster2. Where there is progress, solutions are largely fragmented and piecemeal, not amounting to confidence-building cooperative movements driving meaningful positive action. Why?

Strand, R. (2024). “Global Sustainability Frontrunners: Lessons from the Nordics”. California Management Review, 66, no. 3 (2024): 5-26.

Mazutis, D., & Eckardt A. (2017). “Sleepwalking into Catastrophe: Cognitive Biases and Corporate Climate Change Inertia”. California Management Review, 59(3),74-108.

O’Rourke, D., & Strand, R. (2017). “Patagonia: Driving sustainable innovation by embracing tensions”. California Management Review, 60(1), 102-125.

Businesses are set up to compete, not to cooperate. This presently extends to sustainability where Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance (ESG) initiatives are deemed a foundation for building competitive advantage. ESG offers a fertile source of issues that can be unlocked to differentiate and position a company’s offering in the market3. Research shows that companies that hold strong ESG value propositions are better placed to recruit, motivate, and retain talent, shape customer preference, and build brand equity. Similarly, consulting firms are proposing that businesses who can accurately measure and manage their ESG performance and talent pool will ‘leapfrog’ their competition4. As such, the ESG landscape is creating opportunities for companies to innovate products and business models, develop processes and craft brand narratives that drive consumer engagement and purchase intent.

On the flip side, such rivalry, is creating a barrier to industrywide climate action based on collaboration. What’s more, companies are often deterred from chasing sustainability innovation and de-carbonisation strategies on their own, due to perceived first mover disadvantages that are costly in the short term with uncertain future payoffs5. To really drive the required gains in the fight against climate change, a spirit of cooperation, rather than competition is therefore required - businesses in and across sectors, pulling together towards a common goal. But how can this be squared with free market businesses that have competition as their very raison d’etre?

We have revisited the concept of Co-opetition to resolve this dilemma. This is an approach drawn from early Game Theory that brought together previously adversarial businesses, for the achievement of common goals. It was successfully applied by computer giants in the 1980s to share protocols that would allow benefits for all and avoid wasteful development. Becoming more embedded in business practice over time, it is presently being applied to lower costs, innovate, and save effort, in the technology, transportation, automotive and clothing sectors6.

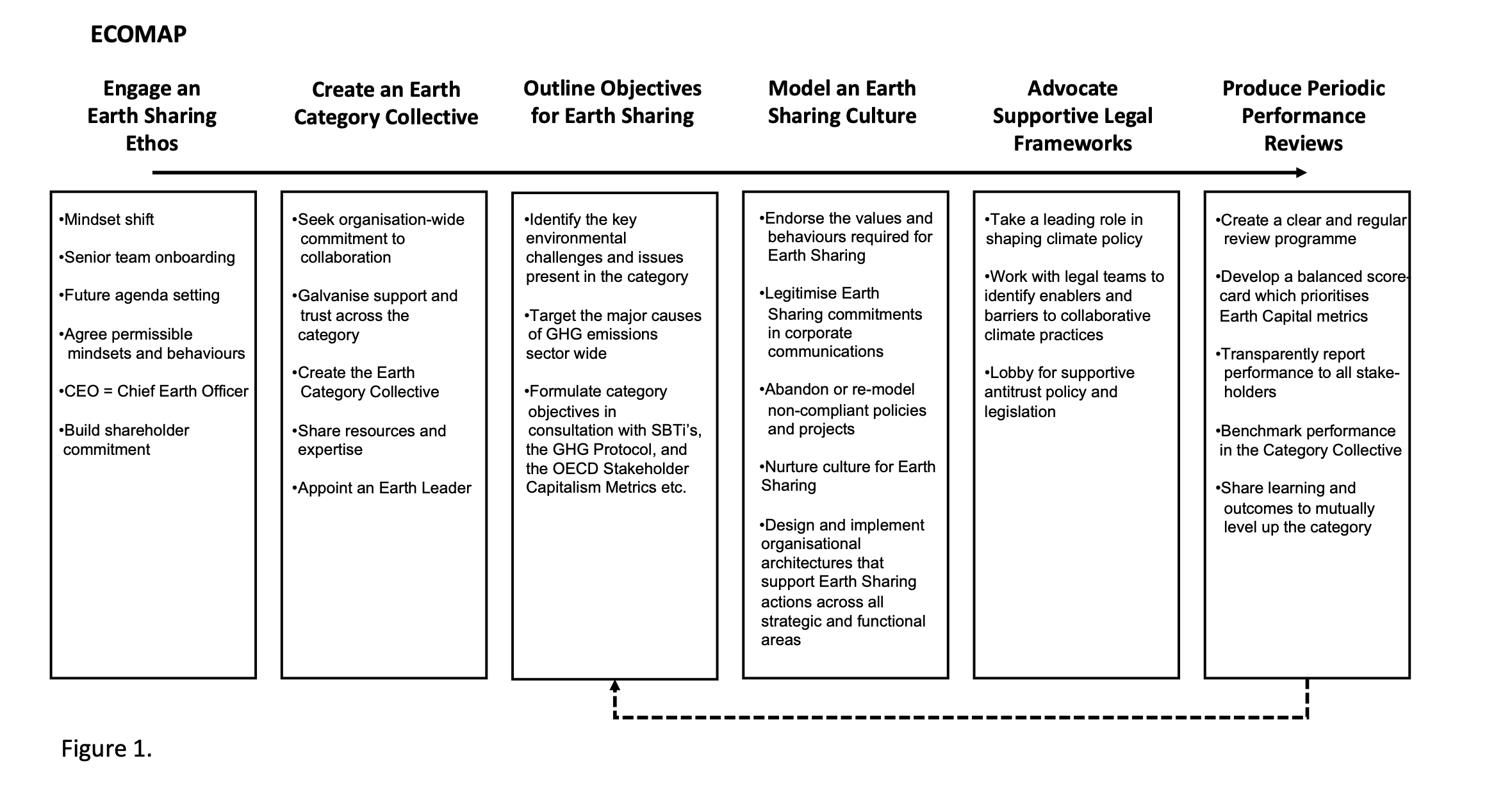

By incorporating these ideas into our thinking, alongside a wider body of climate management research and scholarship, we offer a strategic framework in the form of the ECOMAP (Figure 1) to define six steps for managers to accelerate and support company efforts in the transition to net zero. The logic of the framework is based around collaboration and stakeholder engagement being crucial to confronting the climate challenge through a process we call Earth Sharing. This is premised upon a philosophy of companies pulling together with their category competition to bring about the lasting change that is required to meet the Paris Agreement of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees C above pre-industrial levels. In this respect it shares the sentiment of leading voices in this fight including Mark Carney and the CDP, who are arguing that ‘change needs to happen now’ and that this ‘cannot happen in silos’7.

Most senior leaders have been schooled and incentivised in a profit only paradigm8. A shift in mindset is therefore the first step towards Earth Sharing. Senior teams must foreground environmental sustainability in their corporate mission and embrace nature positive collaborative relationships with their product category competition across the entirety of their value chains.

In outdoor apparel for instance, Patagonia has for many decades been using its products and voice to push an activism agenda to help protect the natural environment9. Most visibly through its ‘Tools for Grassroot Activists’ programme and ‘Patagonia Action Works’. Patagonia’s founder Yves Chouinard was instrumental in the creation of ‘1% for the Planet’ - where businesses contribute 1% of total annual sales to environmental group projects. In 2023, Yves went further and gave his company away, declaring “Earth is now the only shareholder”. The Earth Sharing mindset is fully rooted at this pioneering company.

To underscore its trailblazing spirit, in 2009 Patagonia forged an unlikely partnership with Walmart to kickstart a step change in how companies in the clothing, textiles, footwear and outdoor industries work together to combat climate change. In co-founding the Sustainable Apparel Coalition, Patagonia has been instrumental in shaping the industries response to its record on unsustainability. Having recently rebranded to Cascale (collective action at scale), this coalition, now boasts 300 partners across 34 countries, and draws companies and experts together on a pre-competitive basis to co-create solutions for ‘a nature-positive future’. Amongst other things, this has led to the development of the HIGG index which is a standardized platform for measuring sustainability in the value chain of the consumer goods industries to bring about greater accountability and promote action10.

This is one of the most promising Earth Leadership coalitions to date, and one that is being echoed in Scandinavia by the Swedish Textile Initiative for Climate Action (STICA). Similar in scope to Cascale, STICA has been instigated to bring Nordic brands and climate experts together to develop an action learning network and workstreams to support the wider industry in meeting the ambition of the Paris Agreement. This includes a list of members comprising H&M, Haglofs, Norrana, Peak Performance, and Fjällräven. Their declared mission is clear, “It’s time for action. It’s time for industry innovation. It’s time for Scandinavian and EU leadership”11.

Initiatives like STICA are setting a precedent for Earth Sharing; forging an approach for other companies to follow. Indeed, a recent California Management Review article demonstrates how Nordic companies have pioneered the requisite corporate approach and posture to tackle wicked problems such as climate change through stakeholder cooperation and civic custodianship. This, they call ‘Nordic cooperative advantage’12. It is therefore encouraging to note that US brands, and Patagonia in particular, have set a precedent by being instrumental in shaping cooperative advantage for climate action and sustainability with Cascale.

Earth Sharing entails an organisation-wide commitment to collaboration for climate action across all companies in a competitive category. What we call, an Earth Category Collective. This will require transparency to build trust with partners to facilitate the ongoing commitment that will be necessary to level up the category through the sharing of resources, innovation, and target setting. Each company should identify an Earth Leader, to sit in the C-Suite, with clear ownership and responsibility to facilitate and drive the required commitments across each respective business. This is an area where speed is of the essence, meaningful progress cannot wait decades to be realised.

Environmental priorities inevitably vary across categories and industries. For example, some of the pressing issues in fashion are how to reduce the frequency of purchase, over production, the low levels of product quality, and disposability. Whereas with outdoor clothing the products are generally more robust and enduring. Here the headline focus is on repair, recycling and product renting. Both are chasing better circularity. All must significantly bring down emissions in the value chain. To be effective, the Earth Category Collective must work to identify the key challenges present in their sectors, and how to resolve them. This is about targeting the major causes of GHG emissions sector wide, not tinkering with headline projects that hardly move the needle. This is certainly the case in Fashion, where from 2018, the UNs Fashion Industry Charter for Climate Action began to galvanise the industry towards meaningful progress with greater transparency13. A useful place to start is to consult the SBTi (Science Based Target initiative), which defines targets as needing to be ‘science-based’ - i.e. in line with current climate science to meet the Paris Agreement14. When priorities are established, teams must work to formulate mutually agreed category sustainability objectives with clear targets and timescales for delivery.

Any strategy should match the required culture. Therefore, the bold changes required for Earth Sharing will necessitate a change in organisational climate and priorities. It is vital for the culture to dovetail with the objectives set by the category collective. To minimise their impact on the planet for example, Kartell, the innovative Italian design company, is shaping its sustainability strategy around its “Kartell loves the planet” cultural manifesto “to bring about a convergence of interests” in its value chain15.

Senior teams in each organisation must be clear about the values and behaviours required for subscribing to Earth Sharing. To cement the new organisational culture, these need to be clearly endorsed and disseminated to all stakeholders. With the duty to embed the Earth Sharing Ethos into their organisations and promote cross category climate collaboration, the CEO will inevitably become the Chief Earth Officer.

This step will require new initiatives and practices to be developed and implemented. Importantly, old behaviours and outdated projects should be abandoned or reconfigured. Contradictions will need reconciling. For example, a company cannot espouse a drive to eradicate overconsumption while promoting seasonal discounts for their clothing. All teams and individuals in the organisation must be empowered to deliver on the mutually agreed category targets.

To take root, Earth Sharing must be at the very heart of the re-imagined business model, entwined with operations, marketing, sales, human resources and so on. Crucially this new area needs to be resourced and not simply a loading on top of existing roles and responsibilities. This will require specialist individuals as well as other cross functional talent to be engaged in day-to-day ongoing sustainability focused teams.

Cooperation among competitors, raises antitrust concerns and fears of legal redress. This, in part, spans collective efforts to fight climate change. The authors of a recent Harvard Business Review (HBR) article for example, use an estimate which shows that such fears may presently deter up to 60% of companies from cooperating in this way. They point to building evidence in the US where law makers have sought to investigate companies that may have fallen foul of antitrust legislation based on sustainability projects as a basis for these fears16. The resulting PR piece from these high-profile news stories is clearly off-putting; potentially driving a wedge between companies from collaborating. This can’t set a precedent. So, while the debate between policy makers continues to unfold as to what constitutes legitimate climate collaboration, on a national and international level, companies should not be deterred. They must act and act collectively. To paraphrase the authors of the HBR article, companies need to seek out the necessary assurances from their legal teams as to what constitutes appropriate co-operative behaviour and to build their networks and category collectives accordingly. Second, as the legal context remains fluid, companies seeking to collaborate need to use their combined voices to shape the emerging green antitrust policies to ensure they play a complimentary role in the push to Net Zero. The nascent category collectives must advocate supportive legal frameworks for Earth Sharing and lobby for collaborative climate policy17.

The fixation on shareholder value has in recent decades been an easy measure of the success of a business. It has led many businesses down the wrong path as opposed to looking at a mixed scorecard which includes sustainability, DEI and other desirable areas of progress. It is therefore critical to keep a focus on relevant KPIs. This may well require some serious readjustment versus previous narrow definitions of profit and TSR (Total Shareholder Returns) focused success. Earth Capital metrics should be developed and regularly reported on the balanced scorecard18. The category collective can support each other in defining these so that they are relevant and transparent for all stakeholders in the value chain. This is precisely what is happening amongst the organisations collaborating with STICA and Cascale.

How to design and implement an effective eco-scorecard is a rapidly moving space, so benchmarking and tracking best practice will become a key part of this area. The GHG Protocol is proving an effective starting point, with 9 out of 10 Fortune 500 companies already reporting to the CDP and committing to transparency about their emissions and environmental impact19. The core and expanded set of ‘Stakeholder Capitalism Metrics’ is another20. These ESG performance reporting tools are being jointly developed by the World Economic Forums International Business Council and teams from Deloitte, EY, KPMG and PwC and is a further example of positive collaboration in the fight against climate change and the support of social value creation. This framework brings together ‘universal’ metrics and disclosures that can be periodically reported by companies across all sectors and countries, and contains strategic pillars related to Principles of Governance, People, Prosperity, and the Planet. It is the latter that is most relevant in the cause of Earth Sharing. Herein, the framework details indicators related to climate change, nature loss, freshwater availability, air pollution, water pollution, solid waste, and resource availability.

In conclusion, the immediate global outlook appears to be one of great uncertainty. One of the certainties that we must focus energy upon is the need to mitigate climate change. Without question, we have a clear agenda as business leaders to re-imagine our companies and industries to meet this crisis. We propose a collaborative approach to surmounting this challenge through Earth Sharing.

World Meteorological Organization. (2024). 2023 shatters climate records, with major impacts, November 30. Available at: wmo.int.

Mazutis, D., & Eckardt A. (2017). Sleepwalking into Catastrophe: Cognitive Biases and Corporate Climate Change Inertia. California Management Review, 59(3),74-108.

Almquist, E., Edwards, K., Dowling, P., & King, A. (2023). Does a Purpose Help Brands Grow?. Bain & Company, November 13. Available at: bain.com.

Henisz, W., Koller, T., & Nuttall, R. (2019). Five ways that ESG creates value. McKinsey Quarterly, (November). Available at: mckinsey.com; Also see, Jamison, S., Laue, J., & Coppola, M. (2024). From compliance to competitive advantage: Harnessing ESG regulation to accelerate your sustainability strategy. Accenture. Available at: www.accenture.com.

Culhane-Husain, A., (2023). Reframing Antitrust Law as an Environmental Problem. Yale Environment Review, November 17. Available at: environment-review.yale.edu.

Brandenburger, A., & Nalebuff, B. (2021) The Rules of Co-opetition. Harvard Business Review, 99(1): 48-57.

CDP (2021). “Working Together to Beat the Climate Crisis”. Available at: www.cdn.cdp.net; Also see, United Nations. (2021). Mark Carney: Investing in net-zero climate solutions creates value and rewards. Available at: un.org - :~:Interview, Mark Carney, Investing in net-zero climate solutions creates value,of the Bank of England.

Ritz, R., (2022). Linking Executive Compensation to Climate Performance. California Management Review 64(3), 124-140; Also see Farri, E., Cervini, P., & Rosani, G. (2022). How Sustainability Efforts Fall Apart. Harvard Business Review, [Online], Available: hbr.org [September 2022].

O’Rourke, D., & Strand, R. (2017). Patagonia: Driving sustainable innovation by embracing tensions. California Management Review, 60(1), 102-125.

Kammen, D. M., Hendricks, P., Pendleton-Knoll, S., Stanley, V., & Strand, R. (2018). “Patagonia’s Path to Carbon Neutrality by 2025”, Berkeley Haas Case Series, Haas Scholl of Business, University of California Berkeley.

Sustainable Fashion Academy. (2024). The Scandinavian Textile Initiative for Climate Action. Available at: www.sustainablefashionacademy.org.

Strand, R. (2024). Global Sustainability Frontrunners: Lessons from the Nordics. California Management Review, 66, no. 3 (2024): 5-26.

United Nations, (2024). Fashion Industry Charter for Climate Action. United Nations Climate Change. Available at: https://unfccc.int.

Science Based Targets. (2024). Science Based Targets. Available at: https://sciencebasedtargets.org/.

Kartell (2024) Sustainable Growth and Development in View Of The Agenda For 2030,” Available at: kartell.com.

Gasparini M., Haanaes K., and Tufano P. (2022). When Climate Collaboration Is Treated as an Antitrust Violation. Harvard Business Review, [Online], Available: hbr.org.

Roberts, R. (2024). Why Companies Need to Lobby for Climate Policy, MIT Sloan Management Review , [Online], Available: sloanreview.mit.edu. [22 April 2024].

Thomas M., & McElroy M.W. (2015). “A Better Scorecard for Your Company’s Sustainability Efforts,” Harvard Business Review, [Online], Available: hbr.org [23rd October 2017] (2015).

Greenhouse Gas Protocol. (2024). Available: www.ghgprotocol.org.

World Economic Forum. (2020). Measuring Stakeholder Capitalism: Towards Common Metrics and Consistent Reporting of Sustainable Value Creation, World Economic Forum White Paper, (September 2020). Available: weforum.org.