California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier professional management journal for practitioners published at UC Berkeley Haas School of Business.

by Raj Sharma, Rob Handfield, and Daniel J. Finkenstadt

Image Credit | fanjianhua

In the current environment, the media is calling for bringing more manufacturing and production of pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, electric vehicles, electronics, and many other elements back to the United States. Government innovation programs as well as procurement agencies such as GSA, the Department of Defense, the Department of Homeland Security, and many others are struggling to find the right suppliers. Many of the requirements established by the Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR) and other regulations specify the need for domestic sources (aka the Berry Amendment), diverse and minority owned suppliers, and increased supply chain resilience. Congress has established commissions to evaluate weaknesses within their own planning, programming, budgeting and execution functions in an effort to improve the speed and effectiveness of fielding commercial technologies. And yet, the number of suppliers responding to government RFP’s remains relatively unchanged, despite the plethora of opportunities that abound for US suppliers. So what drives firms away from government markets, and when they’re in the market, what drives them away from specific opportunities? This paper examines this issue and develops insights based on a survey of government suppliers.

“Reassessing the Boundaries of Government,” Anup Srivastava, Felipe B. G. Silva, Hassan Ilyas, and Luminita Enache. California Management Review Insights. Nov 14, 2022.

In 1979 Michael Porter’s prolific article, How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy1 was published describing “Five Forces” of competition that help shape an industry. These forces are primarily sell-side forces in a commercial market. The Porter paper does not account for the host of forces that create barriers in public markets. These public market forces are introduced by government agencies trying to balance the three objectives of public procurement: 1) transparency; 2) value for money; and 3) meeting agency requirements. High public scrutiny blended with governmental policy goals can skew public markets in ways not seen on the commercial side. Researchers have found that government markets differ from commercial markets in terms of customer base, value propositions, risk tolerance, regulation, relationships, size and planning horizon (Josephson et al., 2019).

The landscape of government procurement is evolving rapidly, with increasing pressure to expand domestic manufacturing across sectors from pharmaceuticals to semiconductors. Yet despite abundant opportunities, suppliers remain hesitant to enter government markets. Understanding these barriers—and how to overcome them—has become critical for both public agencies and potential contractors.

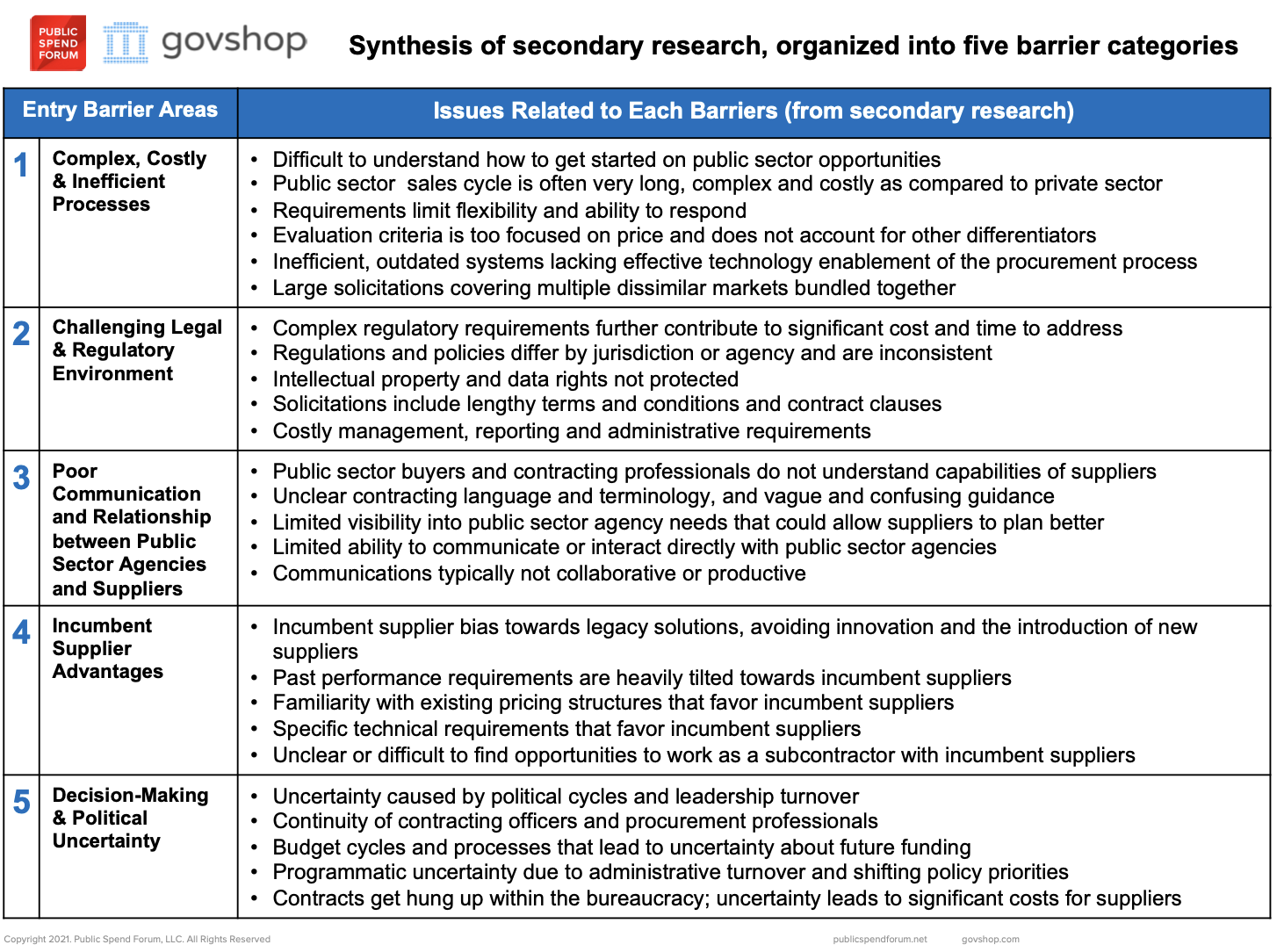

To explore this challenge, Public Spend Forum and NC State University conducted the Barriers to Entry in Government Markets study, building on previous supplier perception research with agencies like the Veterans Affairs Department. Our research began with a comprehensive review of over 20 reports from organizations including the World Bank, Department of Defense 809 Panel, IJIS Institute, OECD, and the White House Office of Federal Procurement Policy.

This analysis revealed five primary barriers that deter U.S. suppliers from entering and exchanging in government markets. While some barriers, like bureaucratic processes, are well-documented, others—including poor communication channels and budget uncertainty—have received less attention despite their significant impact. To validate these findings and gather deeper insights, we surveyed more than 800 suppliers across federal, state, and local markets. The following sections examine each barrier in detail and propose practical solutions for government contracting officers seeking to build more diverse and resilient supplier networks.

Figure 1: Five Barriers to Government Market Entry

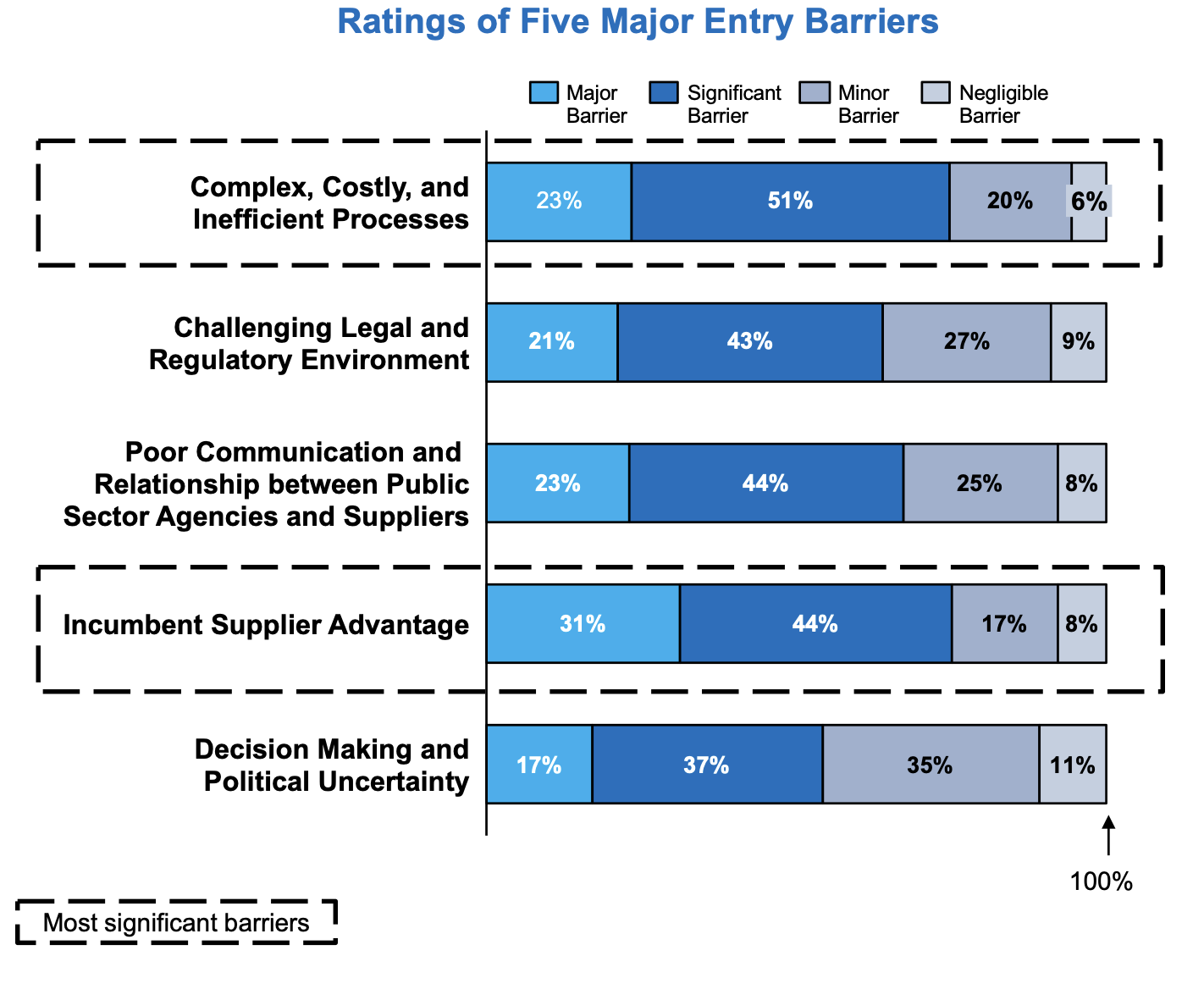

We first examined the strength of each of the barriers. All five major entry barriers were rated as a major or significant barrier by at least 50% of suppliers we surveyed (see Figure 1). Two categories stood out as having the largest total percent of respondents deeming them “major” or “significant” barriers: 1) Incumbent Supplier Advantages and 2) Complex, Costly Processes.

“Decision Making & Political Uncertainty”, to our surprise, had a relatively low rating as a barrier to suppliers. This may indicate that respondents had more challenges in participating in the market versus simply entering it. The other four barriers tend to involve discreet, idiosyncratic impacts that may be within the government’s control whereas “Decision Making and Political Uncertainty” may be seen as issues that are just the standard cost of doing business in any market. These items were explored in more depth, to uncover what some of the underlying issues were.

The single biggest barrier (rated as total barrier rating, less negligible) is the long and costly procurement cycle time for getting an award of new business, which has negative impacts on both companies and government.

Sales cycle time can easily pass 12 months into 2 years. Government programs with critical missions also suffer, unable to bring in emerging technologies and other innovative solutions that are so needed in a time-sensitive manner.

Each year, the U.S. defense industrial base competitively outsources billions of domestically contracted goods and services. Best numbers from USASpending.gov show that figure at around $488 billion for 2022 alone. While this is a sizeable and attractive market, business practices within this industry are quite complex and specialized due to a highly regulated federal acquisition environment. Smaller (often innovative) companies that are bringing new solutions to the market are disproportionately affected due to greater resource constraints. The number of “hoops” small suppliers are required to pass through can be daunting. For example, any firm with a new tech solution has to first pass through a rigorous process called FedRamp, to be granted an “Authority to Operate” designation. Going through this can take 12 to 18 months. This is required to pass the rigorous cybersecurity standards imposed. Other suppliers need to apply under special operating criteria, often associated with SBIR approval. The government cannot simply drop cybersecurity protocols when cyberattacks have been on a dramatic rise in occurrence and sophistication. And FedRamp doesn’t translate to the firm’s commercial business in any value-added way (what is known in transaction cost theory as “asset specificity”). Many investments needed to get government contracts cannot be recovered through use on commercial sales. This creates a tension between investments in public market access and national security that must be adroitly balanced. The mismanagement of this tension leads to a great deal of frustration from all parties.

The FAR (Federal Acquisition Regulations) is one of the most prominent complexities facing new firms. This is a book of acquisition regulations that is several inches thick – and contains multiple criteria and regulations that federal buyers must use to develop requirements, communicate with industry, make sourcing decisions and manage contracts. Many of the pages contain terms and conditions to be levied on firms themselves. Given the nearly 2,000 pages of FAR governance policies defense contracting and procurement activities are highly controlled, if not onerous, relative to commercial practices. This has led to calls to “improve efficiency, reduce red-tape, and provide greater benefit for taxpayer dollars” (Rung, 2014). No less than eight major acquisition reform initiatives have been undertaken since the 1980s (Gansler and Lucyshyn, 2013). The most recent initiative dubbed the Section 809 Panel, was created in 2016 with a charge to “to deliver recommendations that could transform the defense acquisition system to meet the threats and demands of the 21st century.” This panel provided 98 recommendations for improving the US federal defense acquisition system alone.

While such initiatives have focused broadly on contracting activities, strategic supplier management represents a recurring focus for cost improvements and performance benefits (GAO Forum, 2006). For these and many other reasons, evaluation criteria and requirements are seen as onerous and locking out competition. Compounding the sales cycle challenges are evaluation criteria which are seen as generic and too rigid, precluding innovative companies from fully demonstrating the value they can bring to supporting public agency missions. Rigidity of requirements also further prevents suppliers from proposing innovative and potentially more cost-effective solutions. What makes it worse is when an investment is made on an RFP, and it is suddenly cancelled. Volume uncertainty is a transaction cost incurred from the firms’ inability to forecast volume requirements in a relationship (contract etc.). For example, the uncertainty the firm has regarding options being exercised on current contracts or the probability of winning new government contracts in the future. Nontraditional defense firms have more to lose from unsuccessful offerings and from using capital to support the government at the expense of competition in the commercial market due to finite resources.

As one supplier noted:

[It is] Costly for small business to allocate funding for opportunities when the Government then proceeds and cancels the entire opportunity with rationale they changed their mind”

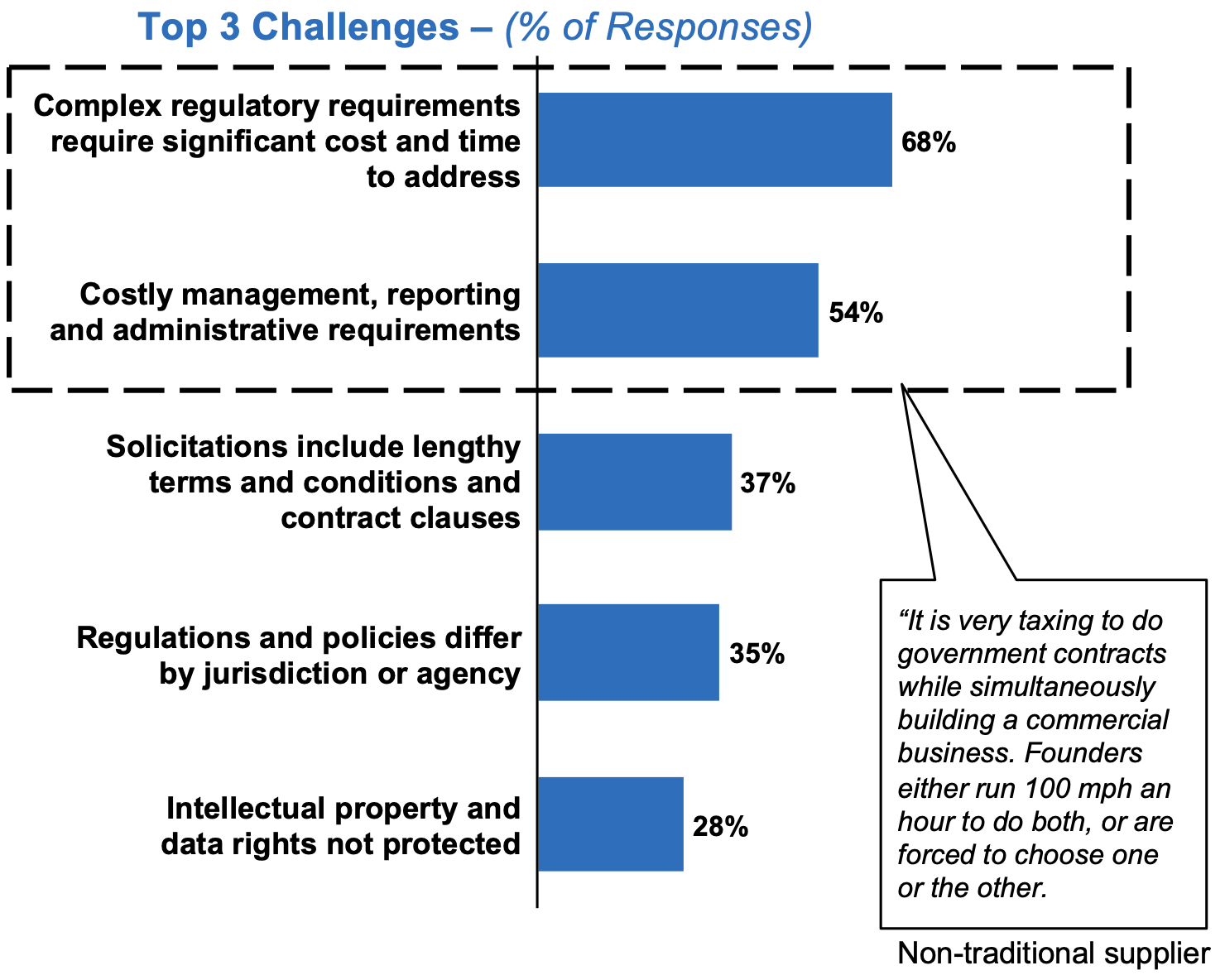

Regulatory and administrative requirements often act as barriers and result in significant additional costs. Businesses are directly impacted by regulations and administrative requirements that impose immediate costs and require scarce resources. In fact, smaller businesses are often forced into a position where they simply cannot compete due to resource constraints which larger businesses are better positioned to absorb. As one supplier noted:

“It is very taxing to do government contracts while simultaneously building a commercial business. Founders either run 100 mph an hour to do both, or are forced to choose one or the other.

Researchers have suggested that firms wishing to operate in government markets should become “purists” vs. “tourists”, essentially devoting all efforts to government sales and relationship management. Their findings seem to resonate with the data in our survey. This is an unfortunate outcome given the government’s increased focus on non-traditional sourcing partnerships that draw benefit from the innovations generated through commercial market forces.

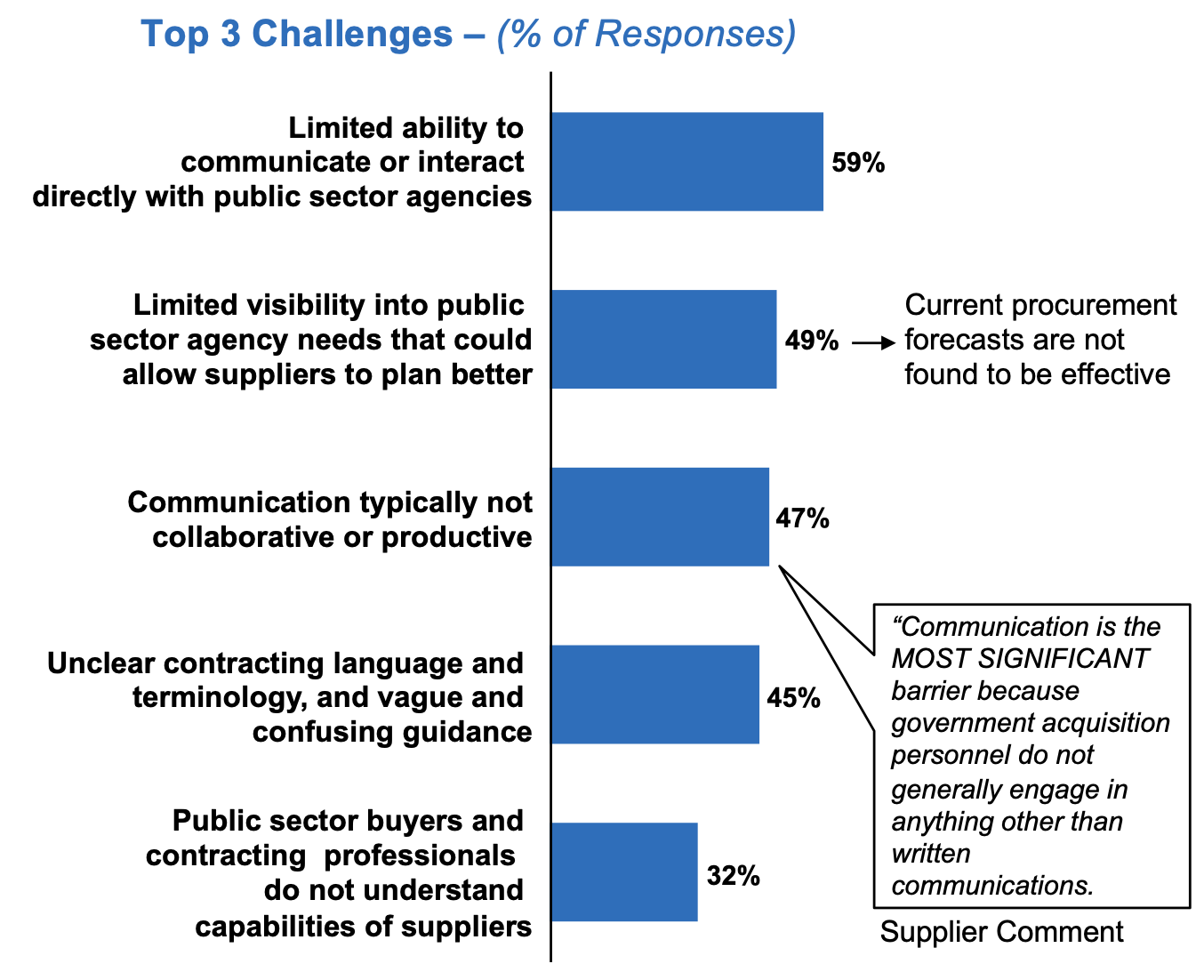

The ability to communicate with government officials continues to be a major barrier, although it has improved over time. Simply finding someone who can explain the requirements is impossible – program and acquisition officers are often overwhelmed with work, and cannot answer the phone. Also rooted in the widespread norms and culture of public procurement are the practices that keep government officials from communicating with suppliers. But the good news is that this is widely acknowledged with some level of movement towards solutions and culture change. The government has been trying to mandate improvements to its communication with the public since The Plain Writing Act of 2010. Lawmakers continue to push for the law to be expanded to ensure regulations are easier to understand by the general public. The Section 809 Panel also suggested simplifying language by reducing government-unique terms and following commercial terminology when possible. However, to date, little has changed in acquisition communications since the Act was codified.

Suppliers can gain significant efficiencies and save time/money if agencies were to be provide better data and information regarding their procurement plans. While larger companies can put resources to do adequate market research, smaller suppliers lack the resources to seek out information, leaving them to respond at a moment’s notice to new and emerging opportunities.

“Communication is the MOST SIGNIFICANT barrier because government acquisition personnel do not generally engage in anything other than written communications.

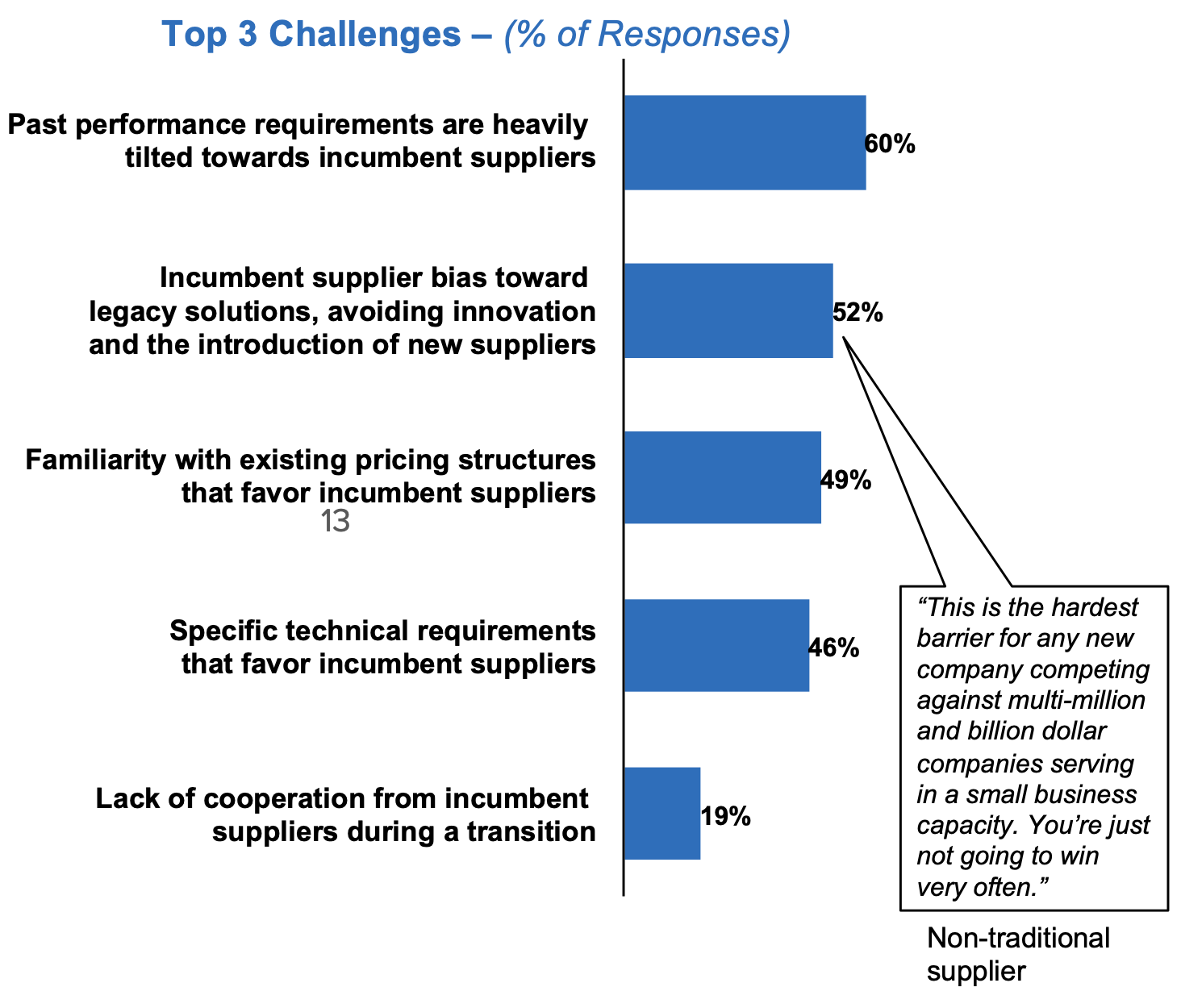

Finally, it is almost universally believed that incumbent suppliers have a distinct advantage over new entrants. While this may be true in any industry, this is especially true for the Department of Defense, which has the usual government focused players such as RTX, Northrop, Lockheed, and Boeing who have a virtual lock on many government contracts. These “primes” also have their own set of suppliers that they often are locked into.

Past performance and other criteria that favor incumbents seen as significant barriers. While past performance is critical and an important factor that should be a key evaluation criteria, it is seen as sometimes too generic or on the other spectrum, over prescriptive even when not deemed critical to successful future performance. Public officials should use more discretion as to which part of past performance is most critical (e.g. experience with a specific agency vs. technical expertise and experience). Past performance questionnaires are also often biased since they are “self-administered”, and rarely are suppliers evaluated based on actual performance which is measurable and reviewed by actual acquisition officers. The government’s main means of recording past performance at the federal level has been criticized for years for being late, incomplete, inconsistent and inaccurate. Rating systems of that caliber do not engender trust and tend to push buyers and evaluators towards household names versus nontraditional sources.

Lack of understanding of business models and pricing structures often drives away qualified companies. Feedback from suppliers also indicates a lack of understanding of business and pricing models leads to many suppliers walking away. This generally aligns with previous research related to lack of strategic market intelligence conducted by government to better understand suppliers, their capabilities and their business strategies including pricing.

Engage suppliers early: Meaningful and collaborative supplier engagement early in the procurement process. The government needs to increase its value co-creation behaviors. Researchers have found for years that value co-creation (collaborative, joint, concurrent and peer-like process of developing requirements and solutions with your exchange partners) leads to better solutions and consumption experiences. Two of the primary co-creation behaviors for successful exchange are communication openness and shared problem solving. While government cannot reasonably commit to such behaviors with every possible source, they can take on strategic communication and market intelligence practices early and often to improve engagement. Examples include Reverse Industry Days and better designed RFIs.

Early and ongoing engagement of suppliers should become a critical priority. Whether it is in general outside of a specific procurement or in support of a procurement, government professionals must focus on engaging suppliers early and having two-sided collaborative dialogue. A second element is to provide suppliers’ visibility and clarity on procurement goals and better forecasts, including visibility into an agency’s goals and procurement forecasts can help suppliers plan better and be more prepared to respond to government needs. Finally, invest in educating suppliers with world-class resources. Too many government websites provide poorly structured information to suppliers. Government leaders should focus on providing clear guidance, messaging and resources that can help small businesses and entrepreneurs learn quickly about their needs and then want to engage. For example, researchers at the Naval Postgraduate School are employing commercial language analysis software to evaluate the readability and complexity of public sector communications such as policies, regulations, laws and standard contract terms and conditions. The results identify major flaws and weaknesses in these communications. Researchers are then using large language model platforms like ChatGPT to suggest rewrites to these public communications in an effort to better comply with the Plain Writing Act of 2010. This is a novel experiment, but needs to make its way into daily operations.

Program and acquisition officers should find ways to streamline requirements including more use of “problem statements”; align supplier evaluation criteria to goals and differentiators. Procurement requirements often limit flexibility and ability to respond with new and innovative solutions to meet the underlying need. Leading government organizations are now focusing on reducing the volume of requirements, focusing on problem statements and engaging suppliers to ensure their input is incorporated. Some researchers from Naval Postgraduate School and the University of Missouri are demonstrating the use of generative AI to help merge early design requirements across a wide swath of stakeholders.

Second, align evaluation criteria should focus on what matters most. Instead of using “schedule, cost, performance” criteria, more sophisticated procurement organizations are aligning evaluation criteria to key differ specific outcomes. Additionally, focus on the key differentiators between suppliers, weighting those discriminators that are directly tied to outcomes and success. As an example, researchers at the University of North Carolina and Naval Postgraduate School have successfully demonstrated the use of commercial discrete choice modeling typically used for marketing, to assist government personnel in identifying the most important and discriminatory evaluation criteria in advance of a solicitation to ensure evaluation criteria are efficient and meaningful. The Department of Homeland Security is looking at text analysis as a means of evaluating past performance relevancy to increase efficiency and effectiveness in proposal evaluations.

Actively develop and implement programs and procedures targeted specifically at innovative and emerging suppliers. This will involve going beyond leveraging new channels and methods for public agency opportunity marketing - leading agencies are making a focused effort to attract emerging and innovative suppliers. These techniques range from facilitating introductions between existing “larger” companies and the smaller emerging companies (e.g. for purposes of subcontracting opportunity participation) to using new authorities to modifying traditional procurement requirements to ensure barriers to participation are reduced, such as relaxing asset specificity transaction costs for accounting-compliance by utilizing what are known as “other transaction” authorities. Leading organizations are also addressing financial and cost pressures faced by smaller companies. Leaders recommend a variety of tactics to further address economic challenges faced by smaller companies. One example, for instance, a “milestone zero” payment can be structured to ensure there is some cash made available at the outset. Typical public contract financing rules make early cash payments more difficult.

However, this creates a delicate balance: while early financing helps innovative small businesses participate in government contracts, it also increases financial risk if those companies fail to deliver. Procurement officers must carefully evaluate financial stability and past performance while still maintaining opportunities for new entrants. Some organizations are exploring alternative approaches like reduced payment terms, lower proposal costs, and strategic teaming arrangements with established contractors to mitigate these risks while still enabling broader market participation. The goal is to reduce entry barriers without compromising fiscal responsibility.

Remove unneeded terms and conditions and onerous paperwork that increases costs for both suppliers and government. Leading procurement organizations in government recognize the cost of doing business with government for smaller companies is too high, leaving many on the sidelines. They are focusing efforts to take out as much cost as possible so the “cost of sale” as well as timeline is reduced. More focus is shifting towards automation of the procurement process. Automation offers many benefits including compliance, standardization and reduction ins costs/time. All of these benefit government as well as suppliers.

Improve messaging, materials and resources; provide more transparency into public agency opportunities and aggressively market to non-traditional suppliers. Leading organizations see marketing to suppliers as a key role of procurement and the responsibility of the leadership and not just procurement staff. They are using various methods and investing meaningful resources to educate companies on why they should work with government and to attract more companies to the market. Innovators are meeting companies where they may gather, for example on social media or through innovative mediums. Finally, it is key to build on transparency and open access to public agency opportunities, by providing open and transparent information on opportunities is just the start to marketing public agency opportunities for suppliers. Leaders recommend going beyond simply posting opportunities on public agency web sites as well as going beyond “traditional” channels.

Government contracting is never going to be easy. However, there are many steps that can be taken to improve the situation, and to develop a more diverse, nationally secure, and resilient government supply chain. It will require significant changes in the manner in which government contracting occurs. Many of these initiatives have been underway for years, yet our findings show that firms are still struggling in many of the same areas as they always have. It is a difficult task to optimize public trust, government requirements and non-traditional sourcing. However, it is a critical endeavor for national defense that we must continue to pursue. The first step is to admit we have a problem and listen.