California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier professional management journal for practitioners published at UC Berkeley Haas School of Business.

Herman Vantrappen, Francois Barbellion, and Olivier Feix

Image Credit | mrmj

Leaders who are familiar with the “black swan” metaphor, yet never managed to read Nassim Taleb’s eponymous book, might claim that black swans in the past few years have become the new normal.1 That of course is an oxymoron: a “black swan” by definition is a rare and unpredictable event. Nevertheless, it feels to businesses as if every year, if not day, springs a big surprise: a local virus outbreak unleashes a pandemic (COVID), a mega-acquisition changes the name of the game in the industry (Twitter), political insouciance encourages the start of a deadly war (Ukraine), a technological breakthrough captures users’ imagination by storm (generative AI), interest rate hikes trigger the collapse of a beloved bank (Silicon Valley Bank), a new class of drugs promises remedies far beyond the initial indication (GLP-1 receptor agonists), an industrial icon stumbles direly (Boeing), the abusive exploitation of social media algorithms catapults an obscure presidential candidate into pole position (Romania), a structural mismatch between supply and demand multiplies prices and delivery times across the supply chain (electrical power equipment), etc.2

P. J. Schoemaker and G. Day, “Preparing Organizations for Greater Turbulence,” California Management Review, 63/4 (2021): 66-88.

Especially the last example shows that, depending on one’s position, a surprise can be positive or negative, and constitute an opportunity or a threat. The question is: What could and should leaders do to deal as well as possible with uncertain trend inflections and discontinuities (e.g., the slowdown of globalization) or with surprise events (e.g., Credit Suisse’s rescue by UBS)?3 “Corporate foresight” serves as an umbrella term for a variety of concepts and tools that businesses have come to use over the past decades to interpret changes in their business environment, then outline and evaluate plausible futures based on these changes, and finally utilize this information to build and sustain competitive advantages (see Exhibit 1).4,5 Unfortunately, leaders may find that these tools are still failing them whenever they must make sense of unfolding events.

Exhibit 1. Corporate foresight concepts and tools

Various terms have entered the jargon of practitioners involved in corporate foresight.6 Here is a selection:

In this article we describe a pragmatic logic for reflecting on uncertain inflections and surprise events. It helps leaders prepare for the moment when such inflections and events materialize, and to respond to them effectively. It is particularly well suited to guide a discussion about vigilance, vulnerability and resilience at a strategy off-site by the senior leadership team. The logic consists of four steps:

Dealing with uncertainty may feel like being trapped in a giant, frenzied and endless whack-a-mole game. To avoid that fate, one must resist an instinctive, knee-jerk reaction to each and every (weak) signal that is detected. One should first try to make sense of the signal, thereby differentiating secular trends and pivotal events from background noise and one-offs that may be annoying but otherwise of little consequence.

As an example, Russia’s interference in the former Soviet republics is a secular trend, and its annexation of Crimea in 2014 a pivotal event. By contrast, the gyrations of the gold price could be considered background noise, and the occasional repatriation of physical gold reserves by central banks a one-off. The latter example shows also that sensemaking is contextual: What happens to gold is fundamental to commodity-traders, but much less so to biscuit-makers.

The next step after sensemaking is to determine how to deal with each of the retained uncertainties. Of the various factors relevant for qualifying an uncertainty, two stand out:

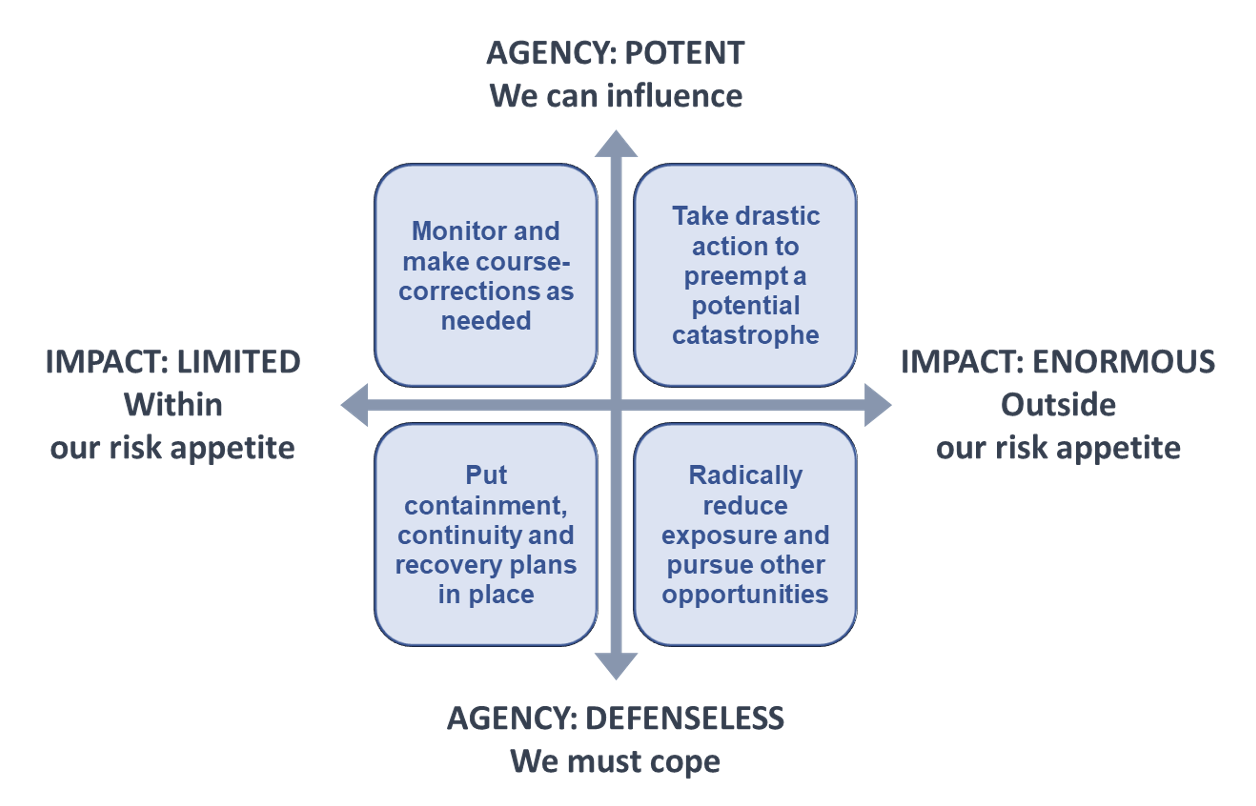

These two factors form a 2x2 grid. The quadrant into which a given uncertainty is categorized informs the type of response to that uncertainty (see Exhibit 2). Exhibit 2. 2x2 grid to qualify an uncertainty

Here are examples for each quadrant:

The next step is to convert the generic responses shown in Exhibit 2 into specific strategic moves. That is because the impact of any specific uncertain inflection or surprise event on a particular company depends on various factors, such as: the clockspeed of the industry in which it operates (for example, life insurance or aircraft manufacturing companies can afford to be more stoical about turbulence than non-life insurance or footwear manufacturing companies); its business model (for example, commodity traders and providers of back-up systems thrive on volatility); and its ownership (private firms in general may have more patient and forgiving owners than listed firms).14

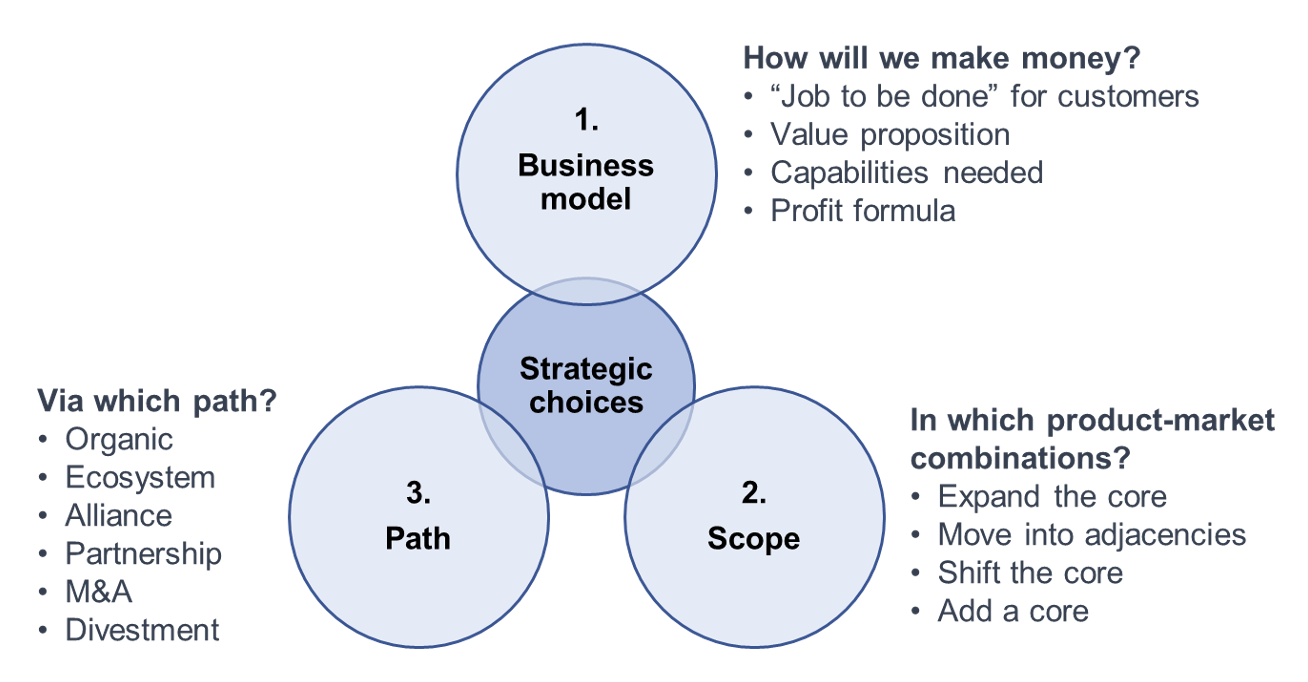

In the context of preparedness for uncertainty we find it useful to formulate a strategic move through three well-known types of choices (see Exhibit 3):

Exhibit 3. The three components of a strategic choice within the context of uncertainty

Let’s take the example of Schneider Electric, a global leader in energy management and industrial automation solutions.15 For a company that is deeply involved in digitization, electrification and sustainability, continual disruption in emerging areas is a source of both opportunity and vulnerability for its core business: The downward trend in the cost curve of a core component may suddenly accelerate or be discontinued; a mainstream technology may be rendered obsolete through a radical innovation; the belief and investment in a disruptive technology may turn out to be a bet on the wrong horse; a new entrant’s legacy-free business model may lead to customer churn; etc. Within that context, Schneider Electric (SE) set up SE Ventures, a venture capital (VC) platform with a broad mandate to invest in emerging areas. One can describe this strategic move in terms of the three abovementioned choices:

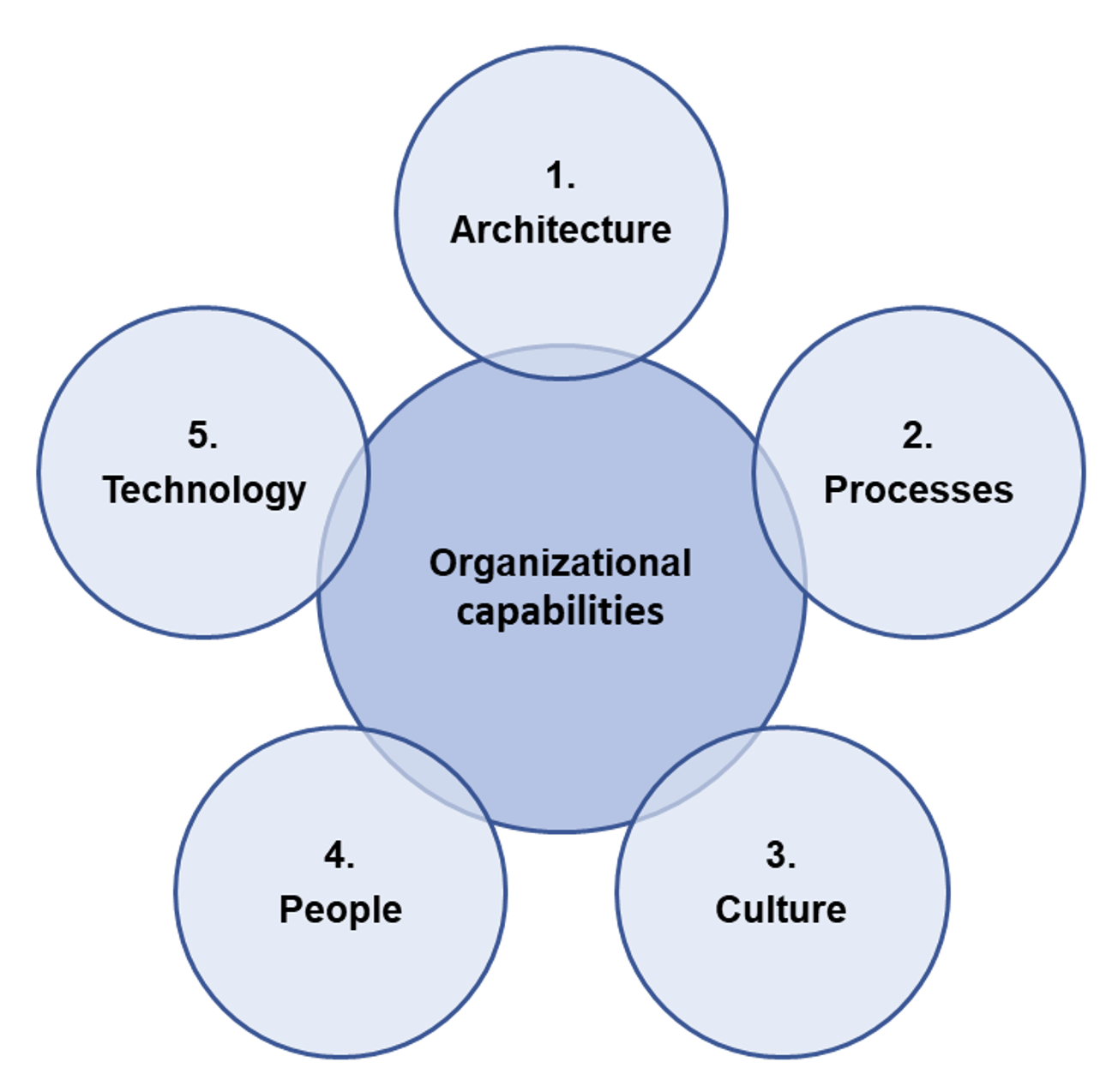

The final step of the logic is to explore whether and where the company may need to strengthen its organizational capabilities in support of its strategic choices. Any such changes are company-specific, but they tend to relate to one of five well-known aspects (see Exhibit 4):16

Exhibit 4. The five aspects of organizational capabilities

The world continues to be rife with uncertainty linked to inflections in trends and surprise events. Uncertainty may be seen as a well of opportunities, but more often it feels like a puddle of vulnerabilities. To prepare an effective response to inflections and surprises, leaders should not rush head over heels into strategic moves or organizational changes. They should make a habit of first qualifying any given uncertainty in terms of its potential impact on the business and in terms of the company’s agency vis-à-vis that uncertainty.

Taleb, Nassim Nicholas. “The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable.” Second Edition, Penguin Random House, 2010.

Shea, G.P. and Allon, G. (2025), “Boeing: wait, there’s more”, Strategy & Leadership, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/SL-10-2024-0111

DHL’s Global Connectedness report of March 2024 strongly challenges the notion that the world has entered a period of deglobalization. The report has been published regularly since 2011 in partnership with NYU Stern School of Business. https://www.dhl.com/global-en/microsites/core/global-connectedness/report.html

Schoemaker, Paul JH, and George Day. “Preparing organizations for greater turbulence.” California Management Review 63.4 (2021): 66-88.

Marinković, Milan, et al. “Corporate foresight: A systematic literature review and future research trajectories.” Journal of Business Research 144 (2022): 289-311.

Gordon, Adam Vigdor. “The place and limits of futures analysis: Strategy under uncertainty 25 years on.” Futures & Foresight Science 6.2 (2024): e176.

Saritas, Ozcan, and Jack E. Smith. “The big picture–trends, drivers, wild cards, discontinuities and weak signals.” Futures 43.3 (2011): 292-312.

Govindarajan, Vijay. “Planned opportunism.” Harvard Business Review 94.5 (2016): 54-61.

Rowe, Emily, George Wright, and James Derbyshire. “Enhancing horizon scanning by utilizing pre-developed scenarios: Analysis of current practice and specification of a process improvement to aid the identification of important ‘weak signals’.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 125 (2017): 224-235.

Schoemaker, Paul JH, George S. Day, and Scott A. Snyder. “Integrating organizational networks, weak signals, strategic radars and scenario planning.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 80.4 (2013): 815-824.

Schoemaker, Paul JH. “Scenario planning: a tool for strategic thinking.” MIT Sloan Management Review (1995).

Kishita, Yusuke, Mattias Höjer, and Jaco Quist. “Consolidating backcasting: A design framework towards a users’ guide.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 202 (2024): 123285.

Chintakananda, Asda, David P. McIntyre, and Tony W. Tong. “Real options: Connecting with other perspectives and exploring new frontiers.” Academy of Management Perspectives ja (2024): amp-2022.

Nadkarni, Sucheta, and Vadake K. Narayanan. “Strategic schemas, strategic flexibility, and firm performance: The moderating role of industry clockspeed.” Strategic Management Journal 28.3 (2007): 243-270.

All factual information about Schneider Electric is drawn from publicly available sources, such as websites, investor presentations and press releases.

Vantrappen, Herman, and Frederic Wirtz. The Organization Design Guide: A Pragmatic Framework for Thoughtful, Efficient and Successful Redesigns. Routledge, 2023.

Webb, Amy. “Bringing True Strategic Foresight Back to Business.” Harvard Business Review, January 12, 2024.

Tunney, Orlaith C., and Jaap Oude Mulders. “When and why do employers (re) hire employees beyond normal retirement age?.” Work, Aging and Retirement 8.1 (2022): 25-37.

Ivanov, Dmitry. “Intelligent digital twin (iDT) for supply chain stress-testing, resilience, and viability.” International Journal of Production Economics 263 (2023): 108938.

Insight

Olaf J. Groth et al.

Insight

Olaf J. Groth et al.

Insight

Egi Nazeraj

Insight

Egi Nazeraj