California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier professional management journal for practitioners published at UC Berkeley Haas School of Business.

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented humanity with an existential crisis. The scientific community – epidemiologists, microbiologists, immunologists and others – will learn many lessons in this battle against the pandemic. The situation should also cause deep reflection among business management scholars, particularly those who study global production and supply networks (GPSNs) which have come under societal scrutiny during the COVID-19 outbreak.

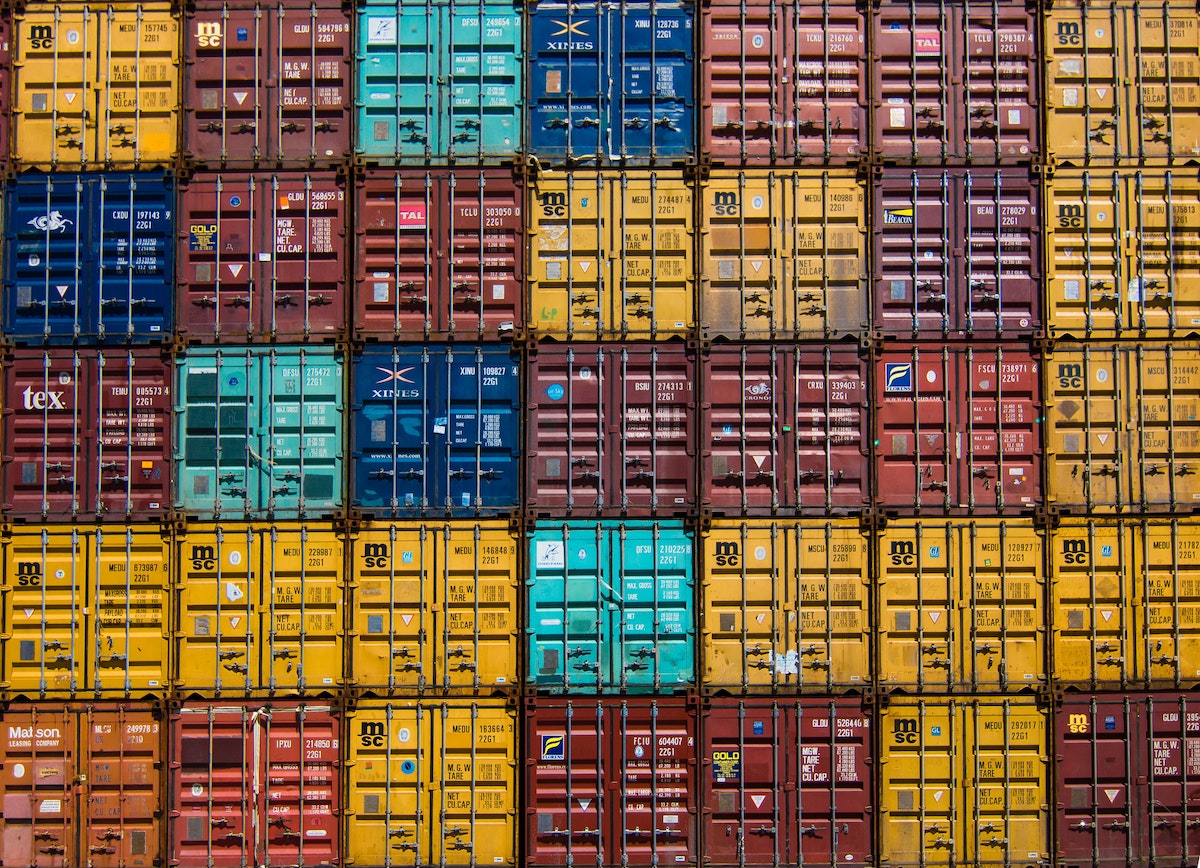

Previously, scholars and activists (comprising concerned investors, consumers, and organizations) have argued that GPSNs are problematic because they fuel human rights violations and cause destruction of the natural environment. It is no news that our garments often come from a factory that subjects children to forced labor; and that ingredients used in our cosmetics, toiletries, and even edibles often cause decimation of the world’s most biologically diverse forests. The COVID-19 pandemic is triggering concerns about GPSNs for yet another alarming reason: public health. As consumers learn that their essential drugs and food items come from far-flung places through extended GPSNs, health concerns are legitimate, as COVID-19 has rendered GPSNs vulnerable.

Management and supply-chain scholars have long argued that any social and environmental concerns emanating from GPSNs can be addressed through collaborative efforts among members of supply networks. However, such collaborative efforts are often ineffective because all members in a given network do not have the same level of commitment to addressing social and environmental problems. An even more profound and critical challenge is intractability of partners in each network. In some sectors – e.g., garment manufacturing – companies downstream in supply networks cannot even precisely identify their GSPNs partners due to largescale unauthorized subcontracting. In other sectors – e.g., forest products – companies downstream in GPSNs are often unable to verify whether their products are free from illegal timber harvesting practices. Even worse, in some sectors – e.g., minerals trade – only a small proportion of companies can confidently state the country of origins of the products that they sell. Using a large, multi-industry dataset, a recent study found that, because of insurmountable challenges of intractability and inherent difficulties in collaborating with far-flung suppliers, global companies are turning to vertical integration so that they can directly control upstream activities.

Vertical integration, however, is likely to cause other complications. This approach is concerning from a social justice perspective, it could lead to marginalization of local communities and hegemonizing of resources by (mostly) Western corporations and local elites in developing countries. This is already evident in natural resource sectors: many Indigenous communities in developing countries have been pushed to the fringes by forestry and mining corporations; and food sector corporations have essentially taken away lands from small farmers through what is dubbed land grabbing. As such, vertical integration is, to put it mildly, a highly undesirable solution to the social and environmental problems that GSPNs create. It sure can help global corporations, but it will quite likely hurt many voiceless, powerless communities throughout the world.

We have been going back, time and again, to corporate-led solutions to address the social and environmental problems that GPSNs create and exacerbate, but to little avail. Management scholars have for the most part, shied away from challenging the basic assumptions of economic globalization. They rather axiomatically assume that economic globalization is good for all and that by designing “effective” collaborative arrangements among GPSN partners, we can address social and environmental challenges that emanate from GPSNs. Sociologists, political scientists, and industrial ecologists have argued that economic globalization might well be pushing us down a dangerous road. It is incumbent upon business management scholars to consider this warning and analyze how local production and supply networks – as opposed to GPSNs – can be fostered. Business Management scholarship that focuses on GPSNs has for long served corporations. Can we be more audacious and address questions that can help protect us from the wraths of GPSNs? It is timely to take up such research that would bring about fundamental transformations in how economies work. Economic de-globalization should be on our research agenda, and the development of local production and supply networks on our list of objectives.

1. Butt, N., Lambrick, F., Menton, M. et al. The supply chain of violence. Nat Sustain 2, 742–747 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0349-4

2. Lambin, E.F., Gibbs, H.K., Heilmayr, R. et al. The role of supply-chain initiatives in reducing deforestation. Nature Clim Change 8, 109–116 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-017-0061-1

3. Simatupang, T. and Sridharan, R. (2005), "An integrative framework for supply chain collaboration", International Journal of Logistics Management, 16 (2), 257-274. https://doi.org/10.1108/09574090510634548

4. Barratt, M. (2004), "Understanding the meaning of collaboration in the supply chain", Supply Chain Management, 9 (1),30-42. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598540410517566

5. Kim, Y.H. and Davis, G.F., 2016. Challenges for global supply chain sustainability: Evidence from conflict minerals reports. Academy of Management Journal, 59(6), 1896-1916.

6. Murcia, MJ, Panwar, R., & Tarzijan, J. 2020. Socially responsible firms outsource less. Business & Society, https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650319898490

7. Saturnino M. B. Jr., Franco, JC, Gómez S., Kay, C., & Spoor, M. (2012) Land grabbing in Latin America and the Caribbean. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 39:3-4, 845-872, DOI: 10.1080/03066150.2012.679931

Spotlight

Sayan Chatterjee

Spotlight

Sayan Chatterjee

Spotlight

Mohammad Rajib Uddin et al.

Spotlight

Mohammad Rajib Uddin et al.