California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier academic management journal published at UC Berkeley

by Debbie Haski-Leventhal, Daniel Korschun, and Martina Linnenluecke

Image Credit | Li-An Lim

For decades, climate activism has mainly been the domain of individuals and anti-capitalism groups. Those activists applied pressure campaigns aimed at embarrassing companies to clean up their act. But in a surprising turn of events, some companies are now among those leading the charge, becoming climate activists themselves. These companies are shifting their focus from fixing their own house to influencing public opinion and policy through climate activism and advocacy. We contend that if we are to make real progress on addressing climate change, more companies are required to do the same. Here is what you need to know.

“Linking Executive Compensation to Climate Performance” by Robert A. Ritz

“Patagonia: Driving Sustainable Innovation by Embracing Tensions” by Dara O’Rourke & Robert Strand

The clock is ticking on climate change. Each of the last four decades has been successively warmer than any decade that preceded it. Warming surface temperatures and oceans are leading to changes in the frequency and severity of extreme weather events, disruptions in food supplies, and the migration of millions. Unless we collectively change course, global temperatures will reach a tipping point, after which it will be all but impossible to fully recover. According to the IPCC’s AR6 Climate Change 2021 report, these alarming trends are “unequivocally caused by human activities”, and it is therefore up to humans to fix it.

If we are to tackle this challenge, industry needs to play a significant role. Businesses are undeniably major contributors to climate change, with 71% of greenhouse gas emissions to be traced to the energy sector alone, and the commercial sector accounts for another one-fifth1. But businesses are also increasingly feeling the impacts of climate change themselves. For example, the increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events2 place an economic burden on many businesses. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reported that 2020 was the sixth consecutive year with ten or more natural disasters that cost more than $1 billion, so-called “billion-dollar events” (the average since 1980, when NOAA began tracking, is 7.1). Worldwide, the picture is even bleaker. Suppliers report that they are bracing for $1.2 trillion in revenue losses over the next five years due to climate factors and may pass $120 billion of that burden down to their buyers. With the stakes this high, it is not surprising that an increasing number of businesses realize that the status quo is falling short of what’s needed to forestall a worst-case scenario.

The business community has indeed made sizable commitments to sustainability, requiring substantial changes to operations. One would be hard-pressed to find a Fortune 500 company that did not acknowledge that it must act responsibly, be a good steward of the environment, and reduce its respective burden on the environment3. Worldwide, companies have become involved in sustainability initiatives for various motivations, including voluntary commitments to reduce emissions and compliance with carbon emission regulations.

However, while most companies are well-intentioned in their sustainability efforts, the traditional approach is no longer enough to achieve the substantial transitions required to mitigate climate change. The root of the problem is that most companies think of climate change through a company-centric lens. The U.N.’s guidelines to business suggest that, at a minimum, companies ensure that their assets are resilient to climate impact, reduce emissions associated with their supply chain, and develop products with negligible emissions. This approach encourages the corporate world to look at its benefits and behavior, such as energy consumption and waste management. However, a company-centric approach is insufficient to tackle what is a much larger collective problem.

This is why some forward-looking companies are shifting toward corporate activism. Corporate political activism refers to the company’s willingness to advocate on sometimes controversial socio-political issues in ways that heighten awareness and influence public behavior to achieve social or political change4. While many companies still have a lot of work to do to recognize their full climate impact, activist companies are pushing ahead with more ambitious emission reduction targets, demanding more stringent regulation, and placing climate change action at the heart of their strategy. This can be seen as the fifth phase of corporate climate action.

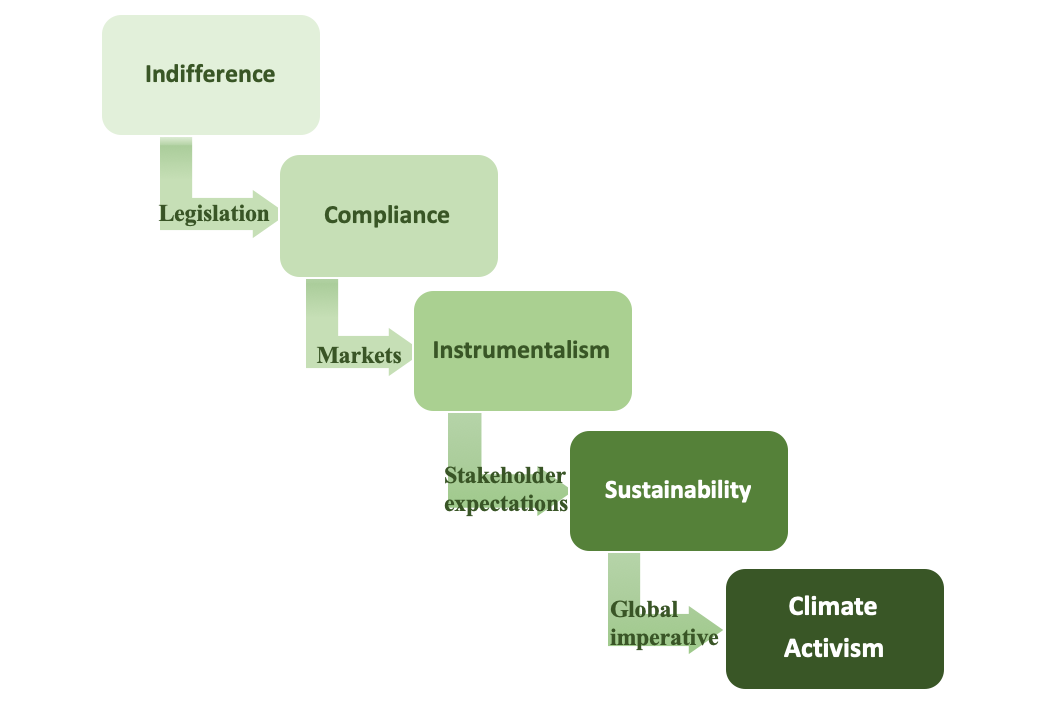

It is possible to trace the evolution of climate action in the last fifty years as a process of five distinct stages with four critical transitions between them (Figure 1). Until the 1970s and through some of the 1980s, most business leaders gave little heed to climate change as an issue, let alone making changes in their organizations to address it. The predominant stance, and the first stage in this model, was indifference. Natural resources were extracted, and waste was disposed-of with little consideration to the environment. It was only after the release of the Brundtland Report in 1987 that a few visionary executives began to consider the issue of sustainability and the dire reality of climate change.

Figure 1 – Five Phases of Corporate Climate Action

The second stage, compliance with legal requirements or voluntary guidelines, develops when companies conform to legislation, industry norms, and international protocols such as the Kyoto Protocol in 2007 or the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals adopted in 2015. For instance, over 11,000 heavy European energy-using installations and airlines are captured under the European Emissions Trading Scheme. They are thus required by law to surrender sizable emissions allowances or pay hefty fines for non-compliance. Unfortunately, compliance can sometimes result in companies doing the bare minimum to meet requirements. And worse, some research suggests that as environmental regulations tighten, companies find innovative ways to pollute elsewhere5. Thus, compliance is a beneficial step, yet still a long way from what is needed. Moreover, compliance ignores the potential business opportunities that a focus on climate change can provide (e.g., environmentally responsible products).

The third stage, instrumentalism, occurs when companies realize that there is a market for being sustainable6. Evidence from the last two decades shows that customers often reward environmental responsibility, leading to potential financial gain for the company7. Sustainability can also reduce waste in materials of operations, resulting in monetary savings. Companies in this phase commonly look for “win-win” outcomes, whereby activities help the environment while simultaneously increasing revenues8 or reducing costs. Of course, companies that use sustainability simply as a tool to make more money may invite criticism that they are motivated more by profit-seeking than a genuine concern for the environment. Greenwashing9 can lead to pressure from employees, customers, suppliers, and other interest groups.

The penultimate stage in our model is sustainability, which is where many well-intentioned companies are today. Rather than look for short-term solutions as companies in the instrumentalism phase do, companies working to achieve sustainability seek longer-term balance and compromise between people, profit, and the planet10. These companies confront tradeoffs between potentially competing interests and adapting to best meet the needs of that stakeholder network11. Sustainable companies change business structure and conduct to minimize negative environmental impact (e.g., reducing emissions) while maximizing positive impact (e.g., replenishing groundwater supply).

However, there is an emerging sense of urgency around climate change and a need for companies to become more active participants in the worldwide conversation. There is a need for companies to consider not only the pressure they sustain from stakeholders but also the potential influence they might have on the public and their stakeholder base.

Therefore, we recommend a shift to the fifth stage, climate activism, which involves using the power of the brand and the company’s resources to promote or counter changes to the existing social order. It targets the public, consumers, governments, other businesses, and all stakeholders, either as allies or opponents fighting for a cause. When companies support controversial issues and movements such as Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, or the LGBTQ+ community, they use their power to change public opinion and behavior. The benefits of addressing climate change go beyond this to include our survival on this planet. Such a shift requires a more transformative approach. Instead of the traditional internal approach, companies elevate toward external influence through leadership, advocacy, and activism.

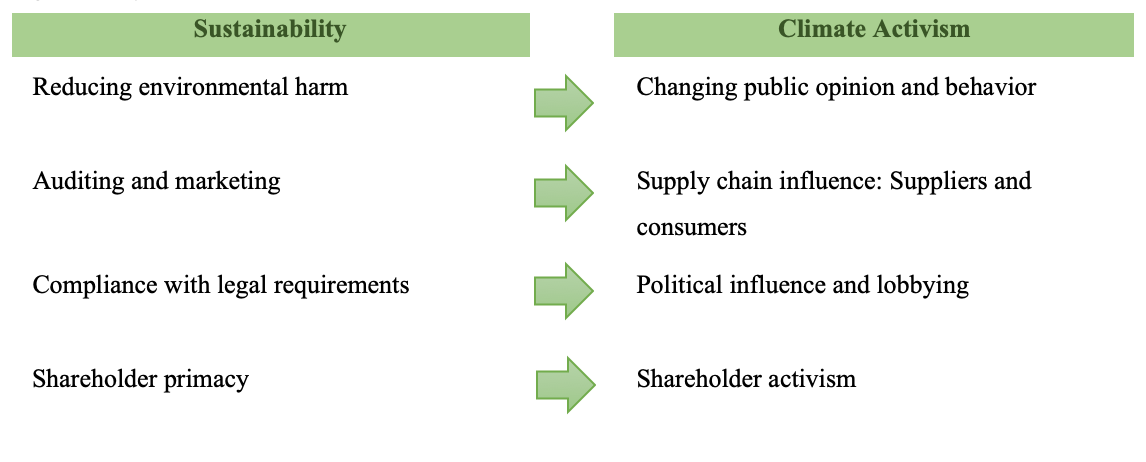

While it is still necessary, we maintain that it is no longer sufficient for companies to focus on reducing their own environmental harm, auditing, and using sustainability in their marketing, complying with legal requirements, and using sustainability to generate wealth for shareholders. The activist company must go further.

Climate activism is a movement mobilizing people and organizations to participate in direct efforts to make individual behavior changes and indirect actions that aim to pressure economic and political actors12. Lyons et al. (2019) defined corporate political responsibility (CPR) as a firm’s disclosure of its political activities and advocacy of socially and environmentally beneficial public policies - not just CSR13. This implies not only giving up old habits but adopting a new mindset. Rather than identify opportunities in the market and adapt to benefit from those opportunities, companies are to start thinking like activists. There are four vital transformations that companies need to take to become climate activists (Figure 2).

Figure 2 – Key Paths to Climate Activism

Companies have voice, agency, and power, which they can channel toward climate activism by influencing public opinion. Some companies are already ahead of the game and support or even initiate social movements with the hope of addressing the most burning issue humanity has ever faced. Companies like Patagonia have paved the way for climate action and now trailblaze a path of climate activism. The American outdoor apparel and equipment company declares it is in the business of saving the planet, and its climate action is holistic and comprehensive. Moving onto climate activism, Patagonia closed its stores in major cities on the climate strike in 2019 and led the Facing Extinction campaign. Founder Yvon Chouinard realized that we must shift to political activism to alter people’s minds and behavior. In the 2020 U.S. elections, Patagonia called voters to vote for those who care about the planet - in a bold political move.

An increasing number of firms now align their corporate identity and values with climate activism. Mike Cannon-Brookes, co-founder & CEO of Atlassian, published a blog titled ‘Don’t F#$% the Planet’, linking climate activism to the company’s core values (‘Don’t F#$% the Client’) and aiming to change public opinion on climate change:

Humanity faces a climate change emergency. It’s a crisis that demands leadership and action. But we can’t rely on governments alone. Sadly, in Australia, we can’t rely on them at all. Businesses and individuals must also play their part and this responsibility is even more urgent when governments fail.

In 2019, IKEA Canada released the ‘The IKEA Climate Change Effect’ ad, showing how the temperatures were increased by four degrees in one of its stores, resulting in complaining customers. ‘We only increased temperatures by 4 degrees’, said the ad. ‘The same amount average global temperature could rise if emissions continue to increase’. The ad ended with IKEA’s promise to reduce its climate footprint by 70 percent before 2030. While IKEA still has sustainability issues in its supply chain, it also aims to change its consumers’ and the public opinion and behavior toward climate action and activism.

These companies utilize their resources, power, and consumer relationship to change public opinion and drive a comprehensive change. They understand that going “carbon neutral” is an essential first step, yet insufficient without a worldwide movement. As IKEA says in its sustainability ad One Little Thing: one little thing done by many can solve many big problems.

The second pathway from sustainability to activism passes through the supply chain. This is important because many large multinational companies have significant supply chains vulnerable to climate change. With a supply chain that extends across various commodities (e.g., cocoa and coffee plantations), Mars could be at risk if farmers face impacts on their crops due to heatwaves, droughts, and floods. Along with Danone, Unilever, and others, Mars formed the Sustainable Food Policy Alliance to advocate for agricultural carbon markets.

However, many companies go further by aiming to create a cascade of sustainability with their suppliers and their suppliers’ suppliers. One recent study shows that supplier compliance with sustainability standards usually does not work. Instead, companies need to create partnerships to change how individuals, groups, and organizations think and act14.

Consumers are also a vital part of climate activism through supply chains. Companies that only concentrate on sustainability often focus on making and selling products to create less waste and pollution. However, without the full collaboration of the consumers, this work is limited. Unilever discovered that for many of its products, from Lipton Tea to OMO laundry detergents, the most significant segment of the environmental footprint occurs with the customer. Through its climate actions and activism, Unilever aims to change this:

We connect with 2.5 billion consumers who use our products every day. Two-thirds of our greenhouse gas (GHG) footprint is from consumer use, and we take responsibility for reducing our impact. But it’s also an enormous opportunity to drive change.

Unilever does this by providing solutions through better products (e.g., laundry detergents that work in cold water), platforms (refill stations for OMO), and educating its customers to change their behavior beyond product use, illustrated in its Take Action website.

Companies have always tried to influence legislation and public policy. CEOs consider regulation to have an enormous impact on performance, which is why many CEOs are spending more and more time with regulators and government officials. According to one recent study, spending on political management efforts can have higher returns than R&D investments . The traditional goal of lobbying has been to protect industries and create market opportunities through legislation and other governmental mechanisms. A pharmaceutical company might seek changes in how the government purchases its medicines.

Using lobbying in climate activism goes beyond the instrumental goals that we have traditionally seen. It is defined as the extent to which firms support public policies that contribute to sustainability16. Berkey and Orts argue that “the climate imperative requires business to ‘get political’ and to lobby and speak out in favor of pro-climate policies, especially given that fossil fuel interests lobby and support candidates in an anti-regulation direction17.

For some companies, climate change presents a business opportunity to increase their competitive advantage and market share. These companies take climate action because of competitive advantages: lucrative investment opportunities in energy-saving or emission-reduction technologies, clean energy solutions, or new options such as the hydrogen economy. However, some companies are pushing legislation that will change the business sector. Beauty Counter, a personal care company, has positioned itself as an advocacy brand in the cosmetics industry. It has been a vocal promoter of legislative reform in the make-up industry and joined “We Are Still In,” a national initiative to push the United States to rejoin the Paris Climate Accord.

Recently, CEOs from over 170 businesses have issued a letter to the Heads of State and Government and European Commissioners supporting the European Green Deal and a clearly defined target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030. As an increasing number of companies realize the urgency of this matter to their business continuity and the survival of humanity, we expect to see more such lobbying and advocacy.

Another critical driver behind the increased action on climate change has been shareholder activism, demanding that companies act on climate change and becoming an essential driver for legitimizing corporate climate activism.

Shareholders were initially urged by the grassroots-led divestment movement to sell off any shares in fossil fuel-intensive investments (and to redirect investments to low-carbon technologies instead) and promote lasting change. Mark Carney, the former Bank of England and Bank of Canada governor, is promoting investors to drive change from within: “Go where the emissions are […] assisting there with the transition is going to make the difference.”

Institutional shareholders are particularly well placed to demand action on climate change, mainly because there is often a social and environmental argument to act on climate change and economic considerations, such as minimizing risk exposure arising from investments in fossil fuels. When companies ignore the environment for too long, their shareholders and employees may start pressuring them more to do so. In 2019, over 7000 Amazon employees signed a petition demanding climate action and justice. Although Bezos refused to meet them, shareholders pressured Amazon to be more sustainable and report its activities. Shareholder activism is an opportunity for companies to work closely with them and other stakeholders toward climate activism.

Climate change is a collective problem demanding a collaborative solution. The current do-it-alone approach, where companies and organizations improve their own performance without much regard for the behaviors of others, is too little too late. If companies are serious about dealing with climate change, they must do the hard work themselves and bring others along for the ride. Because unless we take a joint attempt at this mammoth task, the planet will survive, but we will not be able to survive in it.