California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier professional management journal for practitioners published at UC Berkeley Haas School of Business.

Image Credit | Maxime

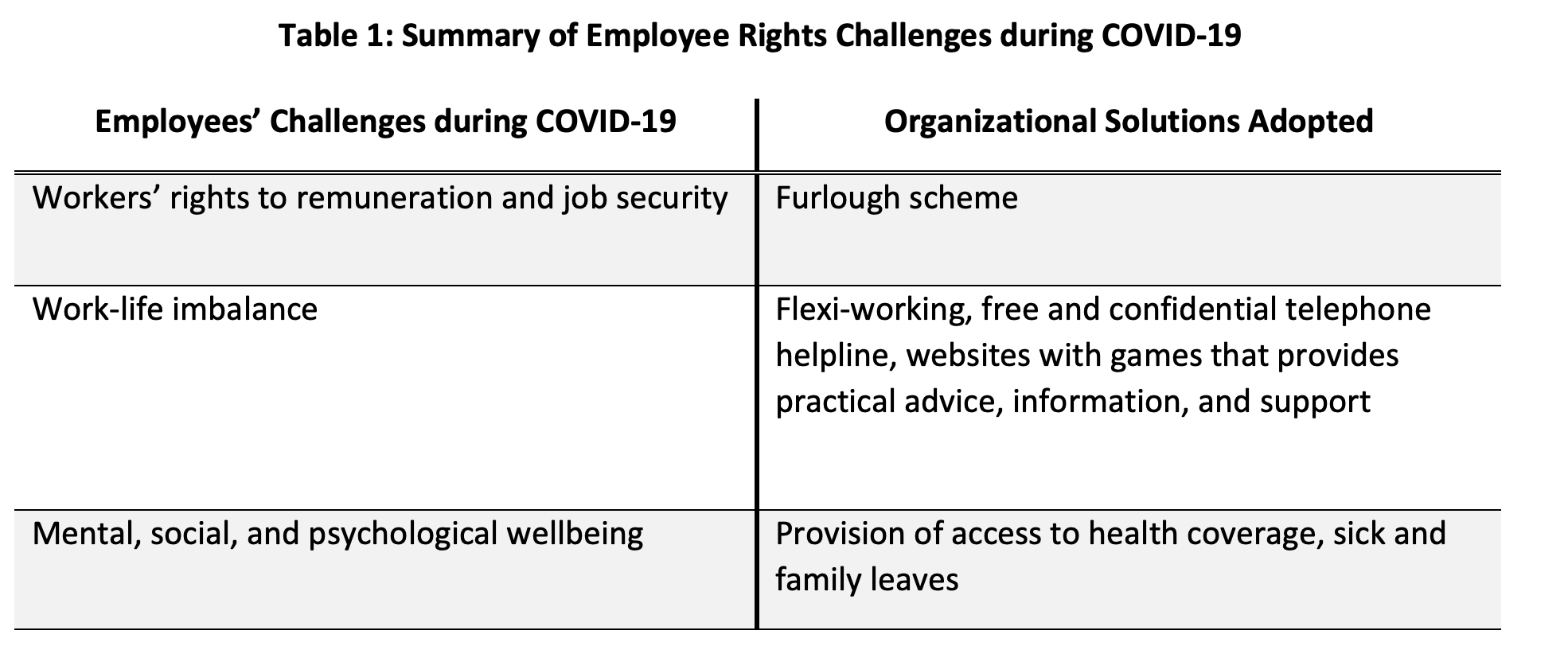

The COVID-19 crisis has impelled the introduction of exceptional measures by organizations to contain the pandemic to ensure employee safety. Protecting workers’ rights is germane in the economy, especially those most vulnerable to limited social protection and income losses. It is important to ensure workers’ rights advance to mitigate the adverse distributional effects of the COVID-19 crisis on workers.1 This issue is even more significant given a setting in which the changing idea of work has been related with a slow ascent in new, non-standard types of business, along these lines testing the capacity of current social protection frameworks to arrive at the employee liable to be in most need of help. Rather than injecting businesses from liability, giving room to engaging in unsafe practices, the staff is encouraged to ensure that safety precautions are in effect. Most of all, employees must be able to avoid working in dangerous conditions without becoming at risk for negative outcomes. Other important measures include proactive outreach to staff to ensure that they recognize their rights, improved access to complaints helplines, and severe punishments for any harassment against such whistle-blowers. Importantly, all staff, including personnel of contractors and suppliers, must have recourse to such guarantees.

“Friedman at 50: Is It Still the Social Responsibility of Business to Increase Profits?” by Karthik Ramanna. (Vol. 62/3) 2020.

“No Team is an Island: How Leaders Shape Networked Ecosystems for Team Success” by Inga Carboni, Rob Cross, and Amy C. Edmondson. (Vol. 64/1) 2021.

Parakh2 acknowledged that while governments are taking steps to bring about a difference in the lives of its citizens during the crisis, it is noted that safeguarding and protecting the health and wellbeing of the public, especially workers entails the implementation of stringent social distancing measures, closure, and lockdown of some business and economic premises and activities, and for employers using bespoke measures in terms of work processes and patterns to ensure their employees’ wellbeing and safety, as well as respecting and honoring their employment contracts and rights. In this regard and recognition of the considerable impact the pandemic has on the mental health of workers, employers of labor need to ensure that even while juggling between office work and domestic chores, employees have their share of mental peace. Hence, firms have launched series of initiatives and activities to help their employees differentiate work time and their family time (a dichotomy that can lead to extended working hours, if not well managed) such as dedicated, free, and confidential telephone helpline; website with games that provides practical advice, information, and support.

To protect the mental, social, and psychological wellbeing of workers, many organizations have mandated and encourage their staff to embark on their vacation as they would do under normal working conditions before the pandemic. From HR and organizations perspectives and about the recent and ongoing Corona Virus (COVID 19) pandemic, the International Labor Organization (ILO) policy brief (Pillar 3: Protecting workers in the workplace) acknowledges that amidst unprecedented worldwide job loss, many workers continue to work in the middle of the crisis and emphasizes the need for organizations across the world to ensure that the workplace is safe and secure for those working and the wages of those not in the frontline is protect no matter what, since the crisis is no fault of theirs.

Statistics from the Business Group on Health3 resonates with ILO (2020) recommendation that the implementation of adequate health and safety measures in critical sectors and well as promoting a supportive working environment to help workers cope during the pandemic is crucial. The ILO further advocate strengthening occupational safety and health measures and facilitating the implementation of public health measures in workplaces; adapting work arrangements thorough measures such as Flexi-working, reduce working hours and work-from-home practices; preventing discrimination and exclusion that can manifest during the crisis for the vulnerable class of workers (such as women, people with disabilities, people living with HIV, indigenous people, ethnic minorities and those in informal sectors); provision of access to health coverage for everyone and improve access of access to paid sick leave and family leave by ensuring immediate access to sickness benefits and reducing waiting periods for payments and developing faster delivery mechanism.

Additionally, Murphy et al.4advocated the need for firms to consider the spectrum of knowledge, skills, and judgment (competencies) during a turbulent period, such as a global health pandemic, as required for smooth operation and safe guiding of workers and the general populace. They were noting that a unique mix of competencies is incredibly valuable in situations of a shortage of workers in critical sectors. In a similar vein, Torda5 catalog a list of ethical and considerable planning decisions necessary during a pandemic, including rationing drugs, rostering of staff, essential resource allocation, evaluation of occupational risk, quarantine, and palliative measures governance issues in affected communities. This decision-making process must, aside from being open, honest, and dynamic, must involve input from a broad of experts across all strata of the economy.

Understanding that workers’ rights during a crisis (pandemic) management would focus more on safeguarding the health and livelihood of the entire society, Almaghrabi et al.6 opined and recommended “adequate and steady provision of PPE, reducing psychological stress, financial support and safety to family members of healthcare workers will increase the willingness to report to work.” More recently, in the bid to protect workers’ rights, most governments have had to issue executive orders and legislations prohibiting all companies and firms from forcing their staff to leave their homes, with perhaps the exemption of workers in vital sectors whose employment is required to preserve or secure their lives or to carry out essential core functions. Companies themselves appoint employees who meet these requirements and are required to follow social distancing strategies and other protection strategies to protect staff as well as the managers in the delivery of the requisite in-person work.7

Economic recovery from the COVID-19 crisis should include protecting workers from economic weakness and from the infection itself. Plans that place workers in perilous conditions will build the danger of the more noteworthy spread of the Coronavirus, making it harder for a vigorous recuperation to grab hold. Policymakers, although find it challenging, are expected to set up more grounded working environment protections while finding a way to help both the employee and employer. Organizations should know that an employee’s psychological wellness difficulties might be set off during this exceptional time of COVID-19 like this. Workers may not be at their best. Their conduct may come from an incapacity that you could conceivably think about; therefore, ensuring employee rights protection will motivate the employee and improve the organization’s performance.

More so, employment rights cannot be overruled even during a crisis; this protect and give the employees the right to refuse any work that may pose a danger to their lives (e.g., contracting COVID-19), the right to be aware of the hazards at work and access to safety information and facilities (e.g., personal protective equipment - PPE), and likewise, the right to participate in programs or committees that associated with health and safety at work. Although, in economic crises, employers may be persuaded to alter some employment pay, benefits, and contract type, however, these changes are not expected to impose decisions that may adversely affect employees’ rights to holidays and leaves, parental rights, flexible working and equal opportunities.

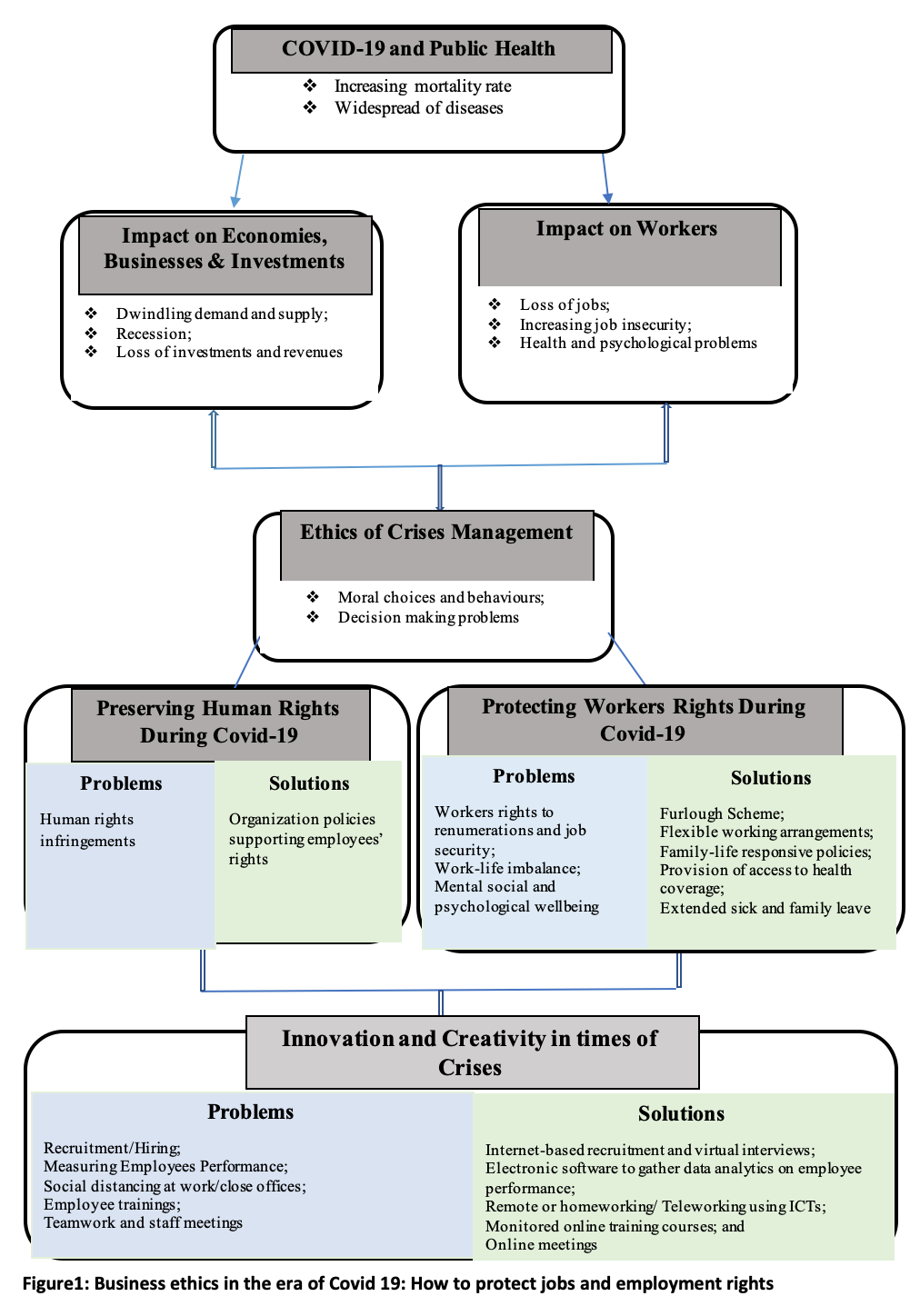

The COVID-19 crisis has imposed certain changes in the organization and the economy at large. In order to stop the rapid progress of the virus and protect public health, most the world’s governmental authorities were under enormous pressure to make necessary but difficult decisions.

While some countries moved quickly to close their territories, stopped international flight, and ordered the general confinement of the population. The crisis has sharply changed the traditional work practice into a greater remote and flexible setting. Employees’ health and safety should be management’s top priority as they are the key factor in building and sustaining performance in the organization. As summarized in figure 1, through the appreciation of the advent of technology, the organization must adopt innovative platforms for collaboration, socialization, and learning to fit the current economic situation. Adaptability in terms of job design, health and safety, and employee wellbeing will be a key attribute of the post-COVID-19 work setting.

Adoption of innovative mechanisms and programs will not only protect the rights of employees but also help to maintain jobs during pandemic situations and economic crisis. Adhering to business ethics will enhance the use of technology and boost the sense of innovation/creativity of both employees and their organizations. The importance of the collaboration between the public Administration, policy makers, entrepreneurs, and employees in order to maintain the fundamentals of business ethics and protect employee’s rights is adjudged to be critical to speedy recovery from the losses and disruptions caused by the pandemic.

Organizations that have just adopted teleworking as a COVID-19 response strategy may consider adopting it as working policies and practices. Therefore, gained experience during the COVID-19 crisis may fit into developing a teleworking policy and procedures within the organization or revising existing ones to ensure employees safety and enhanced organizational performance.

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet, 395, 92–920.

COVID-9. Business World, Retrieved from http://ezproxy.hct.ac.ae/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.hct.ac.ae/docview/2408703?accountid=25

Business Group on Health (2020). Rising health care costs: A Business Group on Health infographic. Retrieved from https://www.businessgrouphealth.org/en/resources/rising-health-care-costs-a-business-group-on-health-infographic

Murphy, G. T., MacKenzie, A., Alder, R., Langley, J., Hickey, M., & Cook, A. (2013). Pilot-testing an applied competency-based approach to health human resources planning. Health Policy and Planning, 28(7), 739. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.hct.ac.ae/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.hct.ac.ae/docview/44280722?accountid=25

Torda, A. (2006). Ethical issues in pandemic planning. Medical Journal of Australia, 85(0), S73-6. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.hct.ac.ae/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.hct.ac.ae/docview/23574986?accountid=25

Almaghrabi, R. H., Alfaradi, H., Al Hebshi, W. A., & Albaadani, M. M. (2020). Healthcare workers experience in dealing with Coronavirus (COVID-9) pandemic. Saudi Medical Journal, 4(6), 657–660. https://doi-org.ezproxy.hct.ac.ae/0.5537/smj.2020.6.250

Abbas, H. (2020, March 28). Whitmer orders Michiganders to stay home during COVID-9 pandemic, except critical workers who “sustain life.” Arab American News, 36(78), 2–3.

Spotlight

Sayan Chatterjee

Spotlight

Sayan Chatterjee

Spotlight

Mohammad Rajib Uddin et al.

Spotlight

Mohammad Rajib Uddin et al.