California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier professional management journal for practitioners published at UC Berkeley Haas School of Business.

by Gilbert Kofi Adarkwah

Image Credit | Markus Spiske

Since the early 1990s, global business interest in developing countries has skyrocketed as many formerly closed economies began opening up to firms from Western economies. During this period of growth, a key mantra was introduced—that executives should “think globally and act locally.” This mantra persists to this day in business schools and has even found its way into several academic articles and textbooks. In 2000, Coca-Cola even made it their main strategy. At its core, the mantra posits that to succeed abroad, firms must adapt their products, services, and practices to the host country’s (local) way of doing business.

“CSR Needs CPR: Corporate Sustainability and Politics” by Thomas P. Lyon, Magali A. Delmas, John W. Maxwell, Pratima (Tima) Bansal, Mireille Chiroleu-Assouline, Patricia Crifo, Rodolphe Durand, Jean-Pascal Gond, Andrew King, Michael Lenox, Michael Toffel, David Vogel, & Frank Wijen. (Vol. 60/4) 2018.

“Friedman at 50: Is It Still the Social Responsibility of Business to Increase Profits?” by Karthik Ramanna. (Vol. 62/3) 2020.

I argue that this approach is risky as it (i) adds significantly to the cost of doing business and (ii) exposes executives to increased personal liability. For instance, it is estimated that illicit payments increase international business costs by more than 10% and add over 25% to the cost of procurement contracts in some countries. Moreover, recent enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act in the US, the EU and the OECD that regard illicit payments to foreign officials as a criminal offense have raised the stakes. Individuals can now be prosecuted in their home country, even when the illicit act occurs abroad. For instance, in 2016, Odebrecht and its subsidiary, Braskem, were fined USD 3.5 billion by the US, Brazil, and Switzerland for bribery of government officials abroad. In addition to the fine, its CEO, Marcelo Odebrecht, was sentenced to a 19-year prison term.1 Thus, “acting locally,” which may require unethical adaptation to local norms and even crossing legal and ethical lines, may put firms and executives at risk. Accordingly, there is a need to reconsider how firms should conduct themselves in distant cultures.

My intent with this essay is not to argue that respect for local cultural norms is bad for business— making products and services relevant to local tastes and preferences remains essential. Instead, I draw on my unique experiences and insights to caution that blind adaptation to the local ways of doing business is a dangerous strategy for firms seeking to enter or grow their businesses in emerging markets. Specifically, I focus on organizational form, internal processes, and procedures as a counterbalance to a national culture of acceptance and perhaps even encouragement of illicit behaviors.

Between 2018 and 2020, I found myself frequently traveling between Europe and several African countries to assist executives of a large European multinational oil and gas company (hereafter, EnergyCo) in identifying and evaluating business opportunities and seizing on them. On one trip, we decided to pay a courtesy call to the tribal chief of the area we were considering investing in. We intended to keep it brief, as it was the first introductory meeting. “We need to bring something for them,” said the Country Director, a local native. “We cannot go to the ɔhene num (chief in the local Akan language) empty-handed!” she insisted. “Why do we need to bring something? asked the CEO. “So that they will like us,” replied the Country Director.After a few seconds of awkward silence, the CEO remarked, “Well, I guess it’s think globally, act locally.”There were laughs all-round the room, but this confusion underscores a real issue facing many Western firms seeking to build or expand their business in emerging markets: how to navigate local cultural and institutional complexities while remaining compliant with home country rules and regulations.

The phrase “think globally, act locally” was born in the early 1970s by environmentalists to encourage individuals to improve their impact on the environment through local action. The phrase was subsequently imported into business schools—marketing and international business programs—in the early 1990s. The argument is that firms, especially those seeking to expand and grow in distant markets, must meet new strategic demands by developing a cadre of globally-minded leaders who can “think globally” but “act locally” on the premise that a lack of local responsiveness is disadvantageous for foreign firms. For instance, in their influential book, Bartlett and Ghoshal (1998)2 suggest that firms must develop strong local management to sense, analyze, and respond to the local market’s needs. I caution that while having a product/service organization to balance local needs is essential to success in culturally distant markets, having flexible internal processes and procedures and succumbing to pressures from unscrupulous local stakeholders, e.g., government officials, chiefs, suppliers, is not. In fact, it may be counterproductive as it creates increased uncertainty regarding firms’ expectations and operational costs in the country. When operating in environments with lax regulations, local stakeholders, especially government officials, are incentivized to engage in opportunistic behaviors whenever they perceive that they have discretion over firms’ behavior. Examples include asking for gifts and payments to facilitate transactions and speed up procedures.3 However, acquiescing to such requests results in wasteful use of firm resources and increased exposure to personal liability for individual executives at home.

The idea for this essay came in 2019 while I was working as CEO Advisor for EnergyCo. At the time, the firm had no presence in Africa, but its executive Chairman and majority shareholder were concerned that continuing to ignore the continent would be at their peril. The Chairman had identified Ghana—one of Africa’s most developed economies and democracies—as key to its aspirations. Ghana discovered oil in commercial quantities in the early 2000s. Consequently, Ghana was billed as the “next African tiger.” “We’re going to really zoom, accelerate… and you’ll see that Ghana truly is the African tiger,” boasted Ghana’s President, John Kufuor. Like Kufuor, EnergyCo’s Chairman was extremely confident about Ghana’s oil prospects. Thus, in 2007, EnergyCo applied for and received a concession contract to explore and produce oil and gas offshore Ghana. However, this contract was abrogated a year later.

In 2007, when EnergyCo applied for a concession contract, its management decided to “act locally.” For instance, in its application, which required partnering with a local firm (to fulfill local content requirements), EnergyCo did not select the most qualified local partner but the most politically connected: a newly established company created by a close friend of the president who had no experience in the oil and gas industry. In 2007, EnergyCo and its inexperienced but well-connected local partner were awarded an exploration contract for a 3,500 km² block. In 2008, John Kufuor’s party was defeated by the opposing candidate, John Atta Mills. The Mills administration decided to investigate all oil and gas concessions agreements awarded by the previous administration prior to the elections. Not surprisingly, the investigations found that EnergyCo’s local partner lacked the qualifications to be awarded a concession agreement. On December 30, 2009, the Energy Ministry revoked the concession award, stating, “The 5 November 2008 agreement was flawed to the extent that it failed to meet the requirements demanded by PNDC L 84. Therefore, the assignment you have requested is legally impossible because of the underlying failure of compliance with the law.” Thus, “acting locally” cost EnergyCo the concessions contract hundreds of millions of dollars and posed a considerable risk to their reputation. Not long after, EnergyCo exited the country.

In January 2018, the Chairman assembled a team of top executives from the parent company to develop a plan for re-entry into Ghana as he continued to see vast potential. To this end, a two-time CEO of publicly traded companies and industry veteran with experience from several culturally distant and institutionally volatile countries such as Qatar, Iran, and Russia was entrusted to lead the company’s second attempt to break into the Ghanaian market. In May 2018, I was recruited to advise the management.

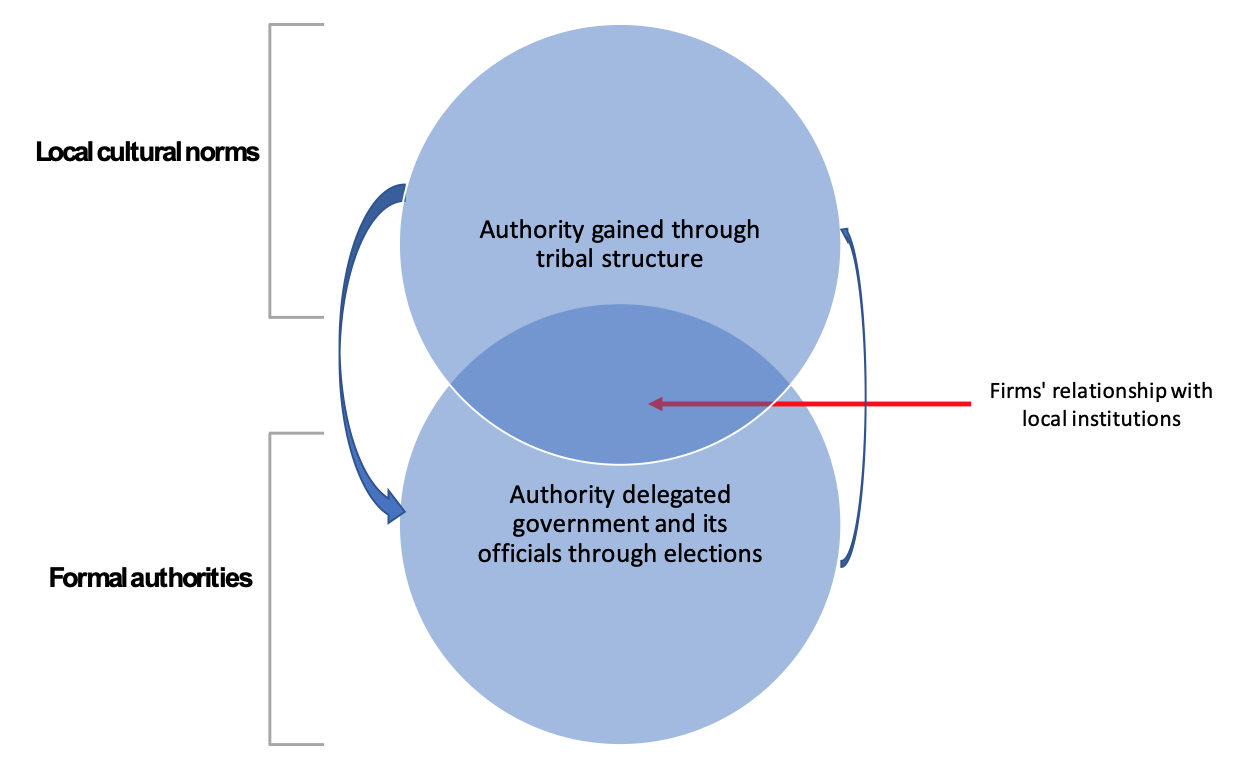

The leadership understood and extensively discussed the critical role of local norms and the need to respect and take them seriously. However, what came as a surprise was the seamlessness and preponderancy of cultural norms in daily business dealings. In Ghana, like many emerging markets, formal authorities and informal norms and practices are thoroughly intertwined. For instance, tribal chiefs and clan elites—informal leadership positions based on kinship and bonds— have long been a central component of the social structure and the system of governance. Individuals occupying these positions are respected and charged with balancing tribal interests and stabilizing the republic. At a more grassroots level, they play a role somewhat similar to that assumed by an official member of the formal government—they adjudicate cases between citizens, codify customary law, celebrate and preserve the tribal culture, and promote socio-economic development. To help clarify the relation between formal authorities and informal norms experienced in Ghana and other emerging markets, I have depicted the formal authorities with informal cultural norms we experienced in Figure 1. As the figure highlights, firms operate at the intersection of formal and informal institutions. Executives’ ability to navigate and manage demands from both formal institutions and informal norms without breaking laws—both locally and abroad—or crossing ethical boundaries is crucial for success in distant markets.

Figure 1: Firms operate at the intersection of formal institutions and informal norms

In emerging markets, informal institutions, shape formal ones and delegate authority to formal institutions. In the remainder of this essay, I highlight how these interpenetrated institutional dynamics affect firms and how executives can navigate such institutions without exposing themselves to liabilities.

Emerging markets are characterized by volatile institutions that are difficult for many firms to navigate.4 Consequently, firms rely on various risk mitigation tools to safeguard their interests in such markets. For EnergyCo in Ghana, this meant de-risking the general institutional environment by pushing for an amendment of local regulations. Among others, EnergyCo wanted the government to relax the rules that required oil and gas firms to seek approval from the petroleum commission for every contract award, viewing this requirement as “unnecessary bureaucracy” that could cause project delays.

Unlike the US or the EU, Ghana, like many developing countries, has no standardized lobbying form. Instead, firms rely on informal networks of influential figures to persuade policymakers. In September 2018, after several months of unsuccessful meetings and discussions with the Ministry of Energy, EnergyCo decided to call on the chiefs to present its case to them. The hope was that they would understand EnergyCo’s point of view and persuade the ministry to amend the laws as the local communities stand to benefit from the projects. As aforementioned, during the preparation for our visit, the Country Director insisted that we bring “something [valuable] for the chiefs.” While laws against corruption abroad have made it possible to prosecute illicit payments to foreign officials and facilitating agents at home, thereby deterring many Western executives from such practices, the same cannot be said of local managers, perhaps due to a lack of social sanctions and generally limited enforceability of accepted practices in these countries. Even after the CEO rejected the suggestion to “bring something” to the chiefs, the Country Director was adamant that such gifts should be given because it is the “local custom.” This may explain why although most firms consider illicit payment and gift-giving a significant obstacle to business, many continue to engage in these activities. From my experience with EnergyCo, the explanation lies in nebulous “local norms” and the desire to be “locally responsive.”

“Your people, they do not understand our culture.”

Acts of gift-giving and illicit payments, aside from increasing the cost of doing business and executives’ liability, also present significant impediments to countries’ economic growth. Although it is hard to estimate, the World Economic Forum5 estimates that such petty payments cost countries more than USD 1 trillion each year. They also undermine the functioning of governments and erode investors’ trust. However, pressure from local representatives, together with the desire to “act locally,” has resulted in neutralizing attempts to enforce uniform organizational forms, internal processes, and procedures to prevent the risk of engaging in acts that may put the firm and its executives at increased risk.

After our meeting with the local chiefs, the Country Director pulled me aside and complained, “Your people, they do not understand our culture. You must advise them! We must be on the good side of all the ɔhene num.” To her, a scenario where the firms operate in Ghana without bowing to pressure of the local norms was unthinkable. She saw the informal institutional structures as essential norms and customs regulating social and economic life that no one should transgress, and she was not alone. Upon reaching an impasse with the commission responsible for awarding licenses for foreign firms, I confided in one senior official to understand their point of view. He counseled me to advise “my people” to make a donation to the commission because “the commission is self-funded,” and a donation from an organization like ours “can go a long way to help the commission’s work.” Clearly, the official was implying that a monetary donation (bribe) would change the commission’s decision.

Back at headquarters, when discussing these gray issues, the CEO revealed that the Country Director had “floated” the idea with him. The CEO looked at the Chief Procurement Officer and recounted, “Remember what I told you when I brought you on board?” “Oh, yes,” he nodded and smiled. “I am not going to prison [for this project].” The CEO continued and recounted the “sad story” of Thorleif Enger, the president and CEO of Yara International, who was accused and convicted along with three other former executives by the Norwegian authorities for paying bribes to officials in India and Libya.6

After several unsuccessful rounds of discussions with government officials and local leaders, we decided to adopt an open approach, that is, to indirectly generate pressure on the ministry by appealing to the public. We were confident this approach would work because it would de-risk the oil and gas sector, making it internationally competitive for investors, something the country desperately needed. We informed all employees of the plan, emphasizing that we were equally interested in the process as we were in the results. We agreed on a one-liner to inform potential stakeholders who may request something in exchange for their help: “I can’t give you a bribe or gifts as this is against headquarters guidelines.” This statement was specifically crafted to ensure that local employees could save face by putting the “blame” on headquarters. We held several meetings with journalists, civil society organizations, formal ministers, and traditional leaders. In fact, we met with almost anyone who would listen, which was an unconventional approach. We did not “act locally.” Instead, we thought globally and acted globally. Finally, on November 1, 2019, the government announced that it would amend the petroleum laws to encourage more investment, and we achieved our goal.

Figure 2: Daily Graphic, announcing the decision to amend the laws

This approach is noteworthy as it safeguards firms against a person or group holding leverage over them or demanding illicit payments. Thus, the experience with EnergyCo shows that foreign firms need not “act locally” to succeed in distant cultures.

Managing firms in distinct cultures is not a walk in the park. As executives catapult into uncharted territories, they may be tempted and even encouraged by the philosophy they acquired from business school to “think globally, act locally.” The temptation is even greater for Western firms because of their ability to pay. Reflecting on it, I cannot help but caution that executives who (i) blindly adopt the adage of “think globally, act locally” can endanger both firms and themselves; (ii) local adaptation may be at the expense of more consequential solutions for both the firm and the host country’s institutional development; and (iii) as a concept, “think globally, act locally” is liable to misinterpretation, which may lead to illegal and/or unethical behaviors. Thus, as business executives, consultants and educators tasked with training the next generation of executives, we must reflect on how we operate in distant cultures. Specifically, we must stress that the process of achieving a result is equally important as the result itself and that firms and executives have a responsibility that extends beyond the area in which they currently operate. An executive may give “gifts” or even pay a bribe to win a contract and, in the short term, increase the firm’s profitability. However, if such illicit payments are uncovered, they may lead to hefty fines and even prosecution, eroding profitability. To resist such temptations to “act locally,” I argue that firms must equally cherish and reward the quality of the process of achieving results as the actual result itself. This requires a strong corporate culture to counterbalance local norms and pressures. Because executives and firms, even foreign ones, have an obligation beyond the communities where they turn a profit. This is particularly so today in a globalized society where both consumers and investors expect firms to do more to help local communities. “Acting locally,” which may require unethical adaptation to local norms and can result in illicit payments, may not be a good strategy since it puts both the firm and the executives at risk.

Dickerson, M., Magalhaes, L., & Lewis, J. T. (2016). Odebrecht ex-CEO sentenced to 19 years in prison in Petrobras scandal. Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/odebrecht-ex-ceo-sentenced-to-19-years-in-prison-1457449835

Bartlett, C., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Managing Across Borders: The Transnational Solution (Vol. 16).

Pinto, J., Leana, C. R., & Pil, F. K. (2008). Corrupt organizations or organizations of corrupt individuals? Two types of organization-level corruption. Academy of Management Review, 33(3), 685-709.

Khanna, T., & Palepu, K. G. (2010). Winning in emerging markets: A road map for strategy and execution. Harvard Business Press

World Economic Forum. (2018). Corruption is costing the global economy $3.6 trillion dollars every year. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/12/the-global-economy-loses-3-6-trillion-to-corruption-each-year-says-u-n

For a recount of this story, see Thomson Reuters. (2016, December 2). Former Yara CEO acquitted of corruption, legal chief convicted. Reuters. Retrieved April 3, 2022, from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yara-intl-corruption-idUSKBN13R0YF