California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier academic management journal published at UC Berkeley

by Daniel Jolles, Odessa Hamilton, and Grace Lordan

Image Credit | Markus Spiske

Generational labels like ‘Baby Boomer’, ‘Gen Z’ and ‘Millennial’ make for seductive clickbait. News feeds are flooded with research articles, editorials and whitepapers that claim to unlock the mysteries of what each generation knows and wants. Meanwhile, social media dishes up satirical videos that stereotype how each generation ‘shows up’ (or doesn’t) at work. But, there is growing concern about the negative influence that these cohort labels can have on workplace attitudes, in addition to the lack of scientific rigour that underpins them.1 A report from the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine questioned the use of generational labels in the workplace, fearing that many generational studies lack rigour and give oxygen to age-related stereotypes that reinforce discriminative practices. Our view, as behavioural scientists, is that we should use generational labels responsibly and do more to understand when and how generations matter.

“Are You Ready for Gen Z in the Workplace?” by Holly Schroth. (Vol. 61/3) 2019.

As it stands, there is no official taxonomy or oversight committee who decide when a new generation starts or ends, or what to name it. Although these labels often evolve organically through popular media and public discourse, many originate from the Pew Research Center, a US Think Tank. Pew defines Generation Z as those born between 1997 and 2004, Generation Y or Millennials as those born 1981-1996, Generation X as those born 1965-1980, and Baby Boomers as those born 1952-1964. Pew has been facing mounting pressure to end their use of generational labels. Last month, they clarified how they will (and will not) use these labels in future research, while encouraging their readers to bring “a healthy dose of skepticism to the generational discussions”.

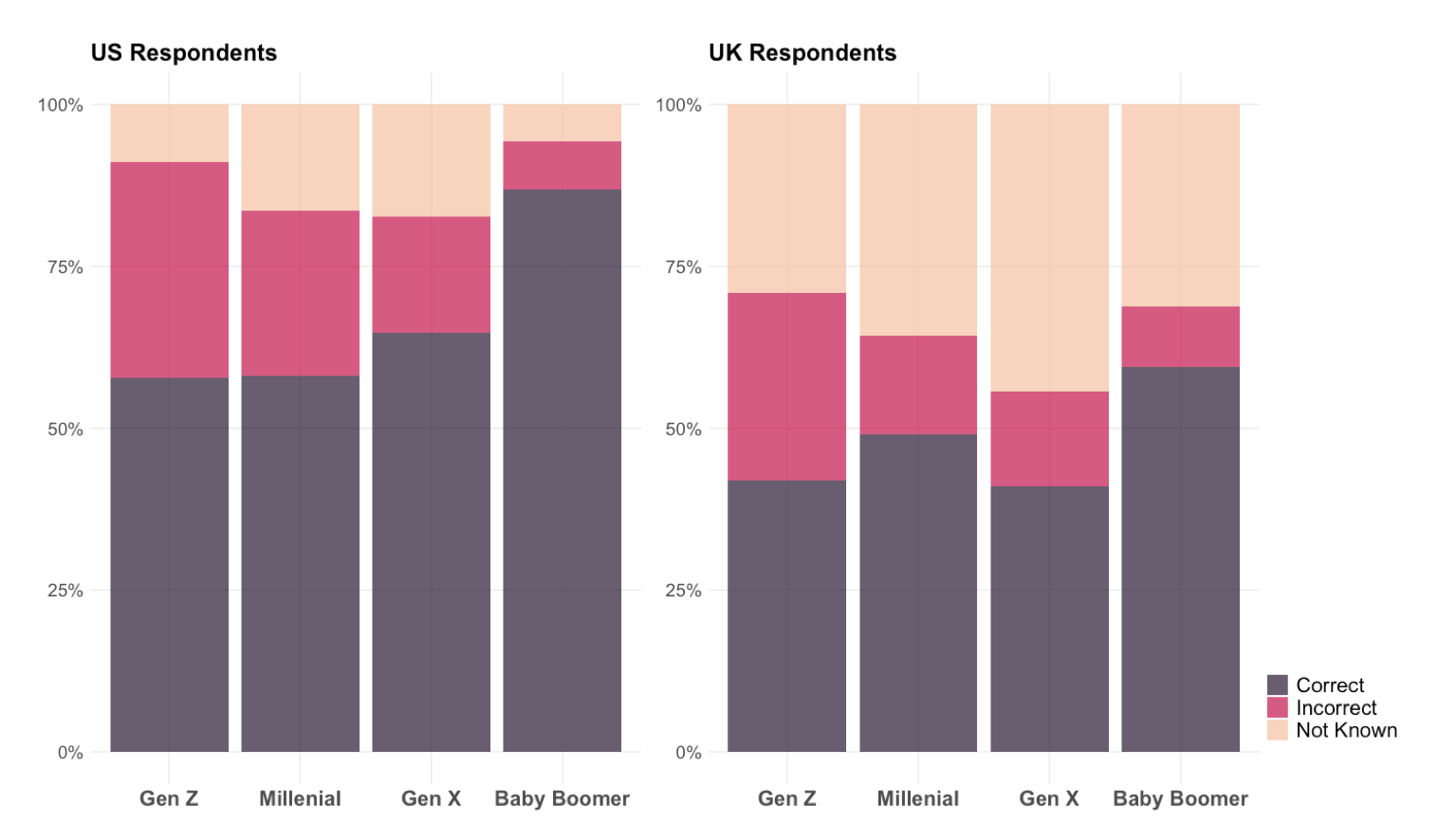

Given the widespread use of generational labels, we set out to understand what they meant to workers. Surveying 1,500 workers across the UK and US using Pew definitions, nearly 60% identified with the generation that they belong to. Within the sample, ‘Baby Boomers’ were most accurate, with 81% identifying their generation, as compared to 51% of the ‘Gen Z’ sample (Figure 1). Many workers thought of themselves as belonging to one of the generations on either side of their own. For example, 9% of Millennials self-identified as Gen Z, while 7% identified as Gen X. This raises the inherent challenges of arbitrary generational cut-off points. Generational labels seem to have much stronger salience in the US than the UK, with only 15% of US workers not knowing which generation they belonged to, compared to 40% in the UK.

Figure 1: Percentage of workers who correctly identify their Generation.

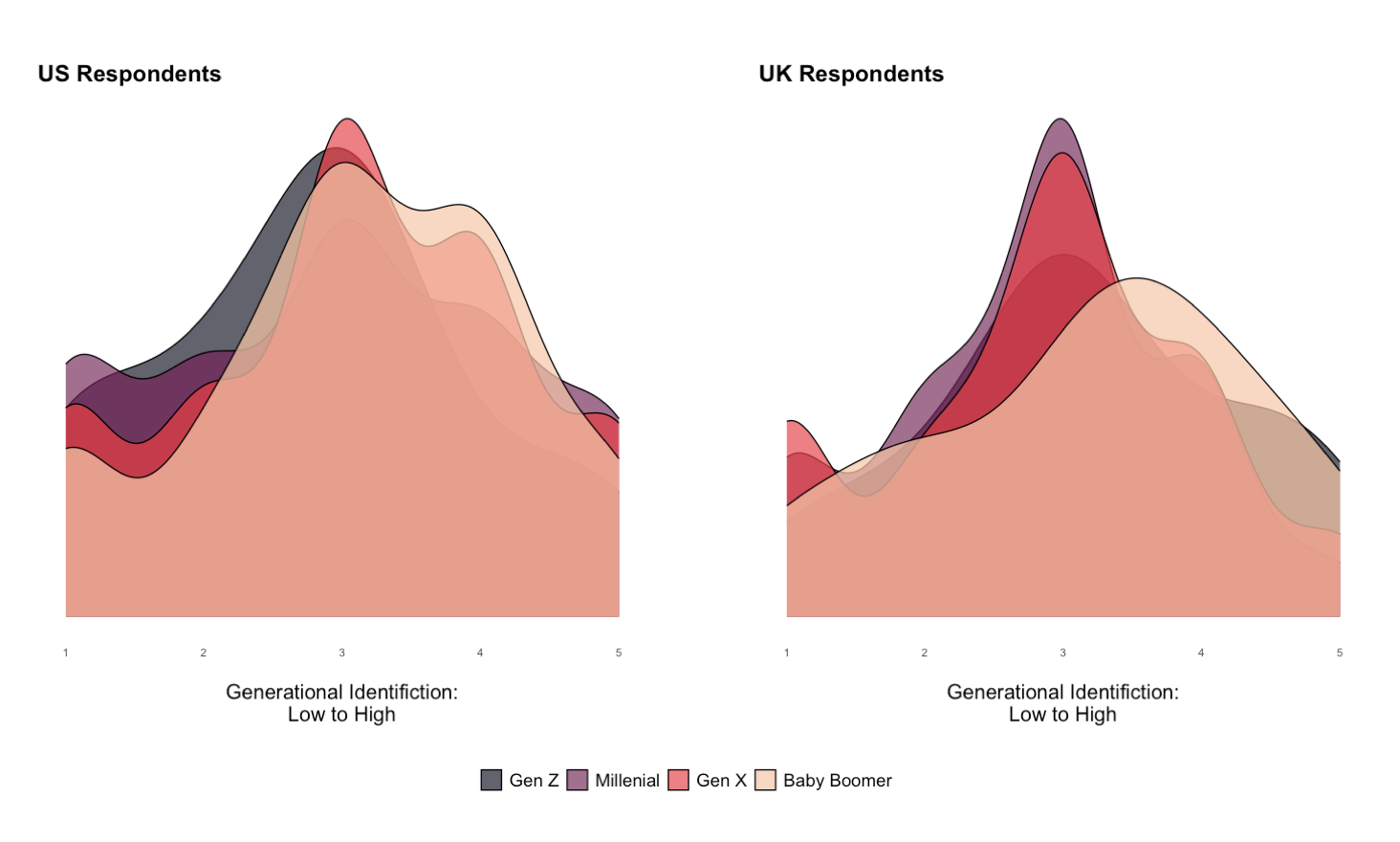

One-third of the sample also felt that the generation that they belonged to was important to their personal identity. This importance was greater for older workers than for younger workers (Figure 2). Thus, not only are generational labels widespread, for many workers they are meaningful to how they see themselves and their place in the world.

Figure 2: Importance of Generation to worker’s identity (by Generation).

Labels aside, ‘generations’ and ‘generational thinking’ are important concepts that can be beneficial when used appropriately. Given that we are living and ,therefore, working longer, most major firms will have five generations working side by side. But regrettably, the productivity benefit of generational diversity often goes unrealised, with generations failing to relate to each other. For example, those from younger generations are sometimes unfairly labelled as ‘snowflakes’ for placing greater importance on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), corporate social responsibility (CSR), and work-life balance than those who came before them.2,3,4 Meanwhile older generations can be unfairly stereotyped as resistant to change or lower performing, leaving older talent undervalued or cast aside too early.5,6 These misunderstandings can create tensions that prevent successful intergenerational inclusion and collaboration.7

It is hard to deny that differences between age cohorts exist when the era that people were born into will have invariably shaped their shared experiences of history. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic will have affected people differently based on multiple factors, including their country of residence, their financial status and, of course, their age.8 Similarly, workplace learning and communication preferences can be influenced by the technologies available to each generation during formative years.9

Generational labels are widespread and widely understood. But rather than rely too heavily on them as a ‘one size fits all’ notion, management decisions about attracting, developing, and retaining talent are better guided by an understanding of ‘generational thinking that recognises and responds to the challenges of an increasingly intergenerational workforce. The challenge ahead then becomes how to acknowledge the importance of generational experience and diversity, while avoiding unhelpful stereotypes and subsequent discrimination. Here, we offer 4 ‘do’s and don’ts’ that will help to this end:

Do recognise the value of intergenerational diversity. Complex problems demand a wide variety of perspectives. Generational diversity is particularly important to tackling complex business problems as it delivers the knowledge, perspectives and connections to increase creativity, innovation, and performance.10,11,12 Sales and service benefit from teams that reflect the generational diversity of their customers, and working in an organisation where people of different ages enjoy positive relationships, free from discrimination, is good for the job satisfaction of every generation.13,14

Don’t use generational labels to reinforce negative stereotypes. Generational labels are socially widespread. There are situations where cohorts share similar experiences or attitudes that are influenced by the era that they were born into. But, as we have shown, there are no absolutes and individuals are not definitively defined by their generation. Labels can be inexact and can veer into unhelpful stereotypes and pseudoscience. They can also be hurtful when they become discriminatory. Creating a team culture that discourages generational divisions and promotes generational diversity drives increased performance.15

Do acknowledge that generational differences exist… Social and economic influences can affect different generational groups differently. For example, degree-educated Gen X’s who graduated university and entered the job market in the 1990s, will have likely had qualitatively different experiences to degree-educated Millennials entering the market post the Global Financial Crisis. For some, these experiences and the labels that accompany them might speak to directly to their experience and how they want to be understood.

…But don’t overstate these differences. Our findings revealed that most workers do not consider their generation to be overly important to who they are as a person, suggesting that managers must not ignore individual experiences by focusing too much on someone’s generational category. And rather than attempt to coin provocative new categories, like ‘Geriatric Millennials’, we must distinguish generational experiences from societal shifts that affect everyone (e.g., increased mobile phone use), or age-related trends that occur at different stages of the life course (e.g., ageing; developing careers; relational changes).

The popularity of generational labels cannot be expected to fade anytime soon. The categorizations provide greater nuance than simply referring to ‘older and younger’ workers and are less arbitrary than referring to groups based on their age bracket. But rather than focusing too heavily on labels, managers can move towards ‘generational thinking’ by recognising the value of intergenerational teams and avoiding stereotypes. This means questioning if the characteristics we observe might persist or change in groups as they age, or if these characteristics reflect broader changes that affect workers of all generations.

Rudolph, C. W., Rauvola, R. S., & Zacher, H. (2018). Leadership and generations at work: A critical review. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(1), 44-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.09.004

Schroth, H. (2019). Are you ready for Gen Z in the workplace? California Management Review, 61(3), 5-18. cmr.sagepub.com.

Singh, R., Chaudhuri, S., Sihag, P., & Shuck, B. (2023). Unpacking generation Y’s engagement using employee experience as the lens: an integrative literature review. Human Resource Development International, 1-29. Human Resource Development International.

Sánchez-Hernández, M. I., González-López, Ó. R., Buenadicha-Mateos, M., & Tato-Jiménez, J. L. (2019). Work-life balance in great companies and pending issues for engaging new generations at work. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(24), 5122. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

Ng, T. W., & Feldman, D. C. (2012). Evaluating six common stereotypes about older workers with meta‐analytical data. Personnel psychology, 65(4), 821-858. Personnel Psychology.

Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2008). The relationship of age to ten dimensions of job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(2), 392–423. Journal of Applied Psychology.

North, M. S., & Fiske, S. T. (2015). Intergenerational resource tensions in the workplace and beyond: Individual, interpersonal, institutional, international. Research in Organizational Behavior, 35, 159-179. Research in Organizational Behavior.

Hamilton, O. S., Cadar, D., & Steptoe, A. (2021). Systemic inflammation and emotional responses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Translational Psychiatry, 11(1), 626. Translational Psychiatry.

Lowell, V. L., & Morris Jr, J. (2019). Leading changes to professional training in the multigenerational office: Generational attitudes and preferences toward learning and technology. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 32(2), 111-135. Performance Improvement Quarterly.

Salas, E., Reyes, D. L., & McDaniel, S. H. (2018). The science of teamwork: Progress, reflections, and the road ahead. American Psychologist, 73(4), 593–600. American Psychologist.

Wegge, J., Jungmann, F., Liebermann, S., Shemla, M., Ries, B. C., Diestel, S., & Schmidt, K. H. (2012). What makes age diverse teams effective? Results from a six-year research program. Work, 41(Supplement 1), 5145-5151. IOS Press

Li, Y., Gong, Y., Burmeister, A., Wang, M., Alterman, V., Alonso, A., & Robinson, S. (2021). Leveraging age diversity for organizational performance: An intellectual capital perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(1), 71–91. Journal of Applied Psychology

Cavusgil, E., Yayla, S., Kutlubay, O. C., & Yeniyurt, S. (2022). The impact of demographic similarity on customers in a service setting. Journal of Business Research, 139, 145-160. Journal of Business Research.

King, S. P., & Bryant, F. B. (2017). The Workplace Intergenerational Climate Scale (WICS): A self‐report instrument measuring ageism in the workplace. Journal of Organizational behavior, 38(1), 124-151. Journal of Organizational Behavior.

Homan, A. C. (2019). Dealing with diversity in workgroups: Preventing problems and promoting potential. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 13(5), e12465. Social and Personality Psychology Compass.