California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier professional management journal for practitioners published at UC Berkeley Haas School of Business.

Tobias Gutmann, Christopher Chochoiek, and Henry Chesbrough

Image Credit | Skye Studios

Open Innovation is one of the most impactful approaches within the field of innovation and a top priority to almost every innovation manager and Tech-Company CTO. In 2003, Henry Chesbrough introduced Open Innovation to the world in his book “Open Innovation: The new Imperative for creating and profiting from Technology”,1 urging firms to look outside themselves for knowledge, license and share their own innovations as well.

“Extending Open Innovation: Orchestrating Knowledge Flows from Corporate Venture Capital Investments” by Tobias Gutmann, Christopher Chochoiek, & Henry Chesbrough. (Vol. 65/2) 2023.

Fast forward to today, and a quick Google search on “Open Innovation” returns over a billion-page links. Looking at LinkedIn, hundreds of thousands of people have job descriptions related to Open Innovation.

Open Innovation covers a wide range of topics, including open source, crowdsourcing, IP licensing, university collaborations, startup engagements, corporate venture capital, supplier-driven innovation, and user innovation – to name a few. All of these processes involve the flow of knowledge across organizational boundaries.

However, large firms face two main challenges when engaging in Open Innovation. The first is managing the associated organizational change internally, and the second is managing external relationships with innovation sources.2 These challenges don’t fit perfectly within the traditional Open Innovation framework, which focuses on Outside-In and Inside-Out knowledge flows.

Additionally, our research found that many of the practices used by the most innovative corporate venture capital units (CVCs) don’t fit within this framework either. In response, we developed an extended framework to guide Open Innovation entities in overcoming these most pressing barriers and increasing their innovation effectiveness.

Let’s start with the traditional Open Innovation Funnel to understand our extended model. In this model, the walls of the product development or innovation funnel are permeable, allowing knowledge to flow across the boundaries between the inside and outside of the organization. This offers the opportunity to manage Outside-In knowledge flows, such as a big corporation partnering with a startup and bringing the startup’s innovation inside the corporate boundaries. It also allows for Inside-Out knowledge flows, such as established firms licensing their IP to the outside world or spinning off corporate ventures.

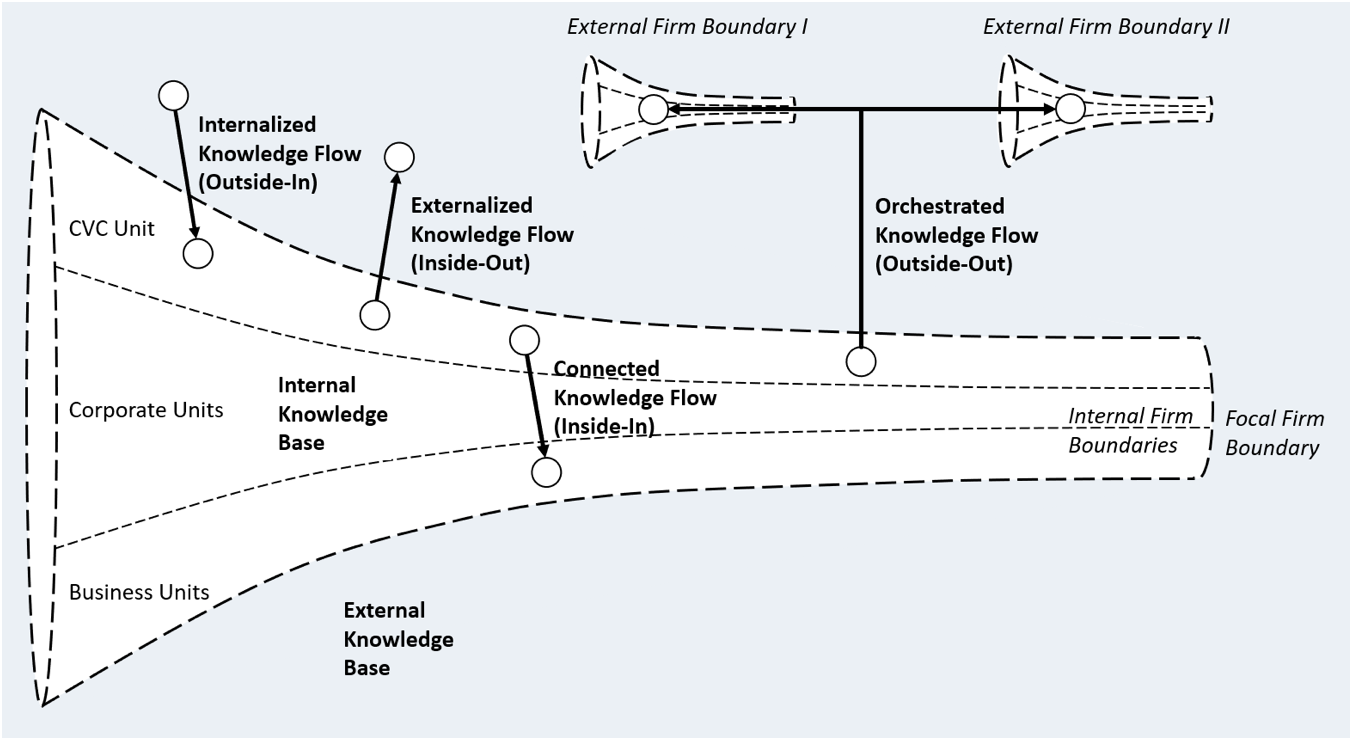

Figure 1: The Extended Open Innovation Model – A CVC Perspective

However, the reality for CVC units (and presumably many other Open Innovation units) looks different. Many internal boundaries prevent them to be effective. A more complete understanding of Open Innovation (incl. CVC) and its successful implementation requires an understanding of its role in increasing the permeability of internal knowledge boundaries, allowing for Inside-In knowledge flows from an Open Innovation/CVC unit to another corporate or business units.

Additionally, some of the most prominent current concepts from innovation management, such as ecosystems, are driven by knowledge flows that also don’t fit within the traditional Open Innovation model. These include Outside-Out knowledge flows, which connect startups to each other and to important customers or complementary partners outside of the firm’s internal boundaries.

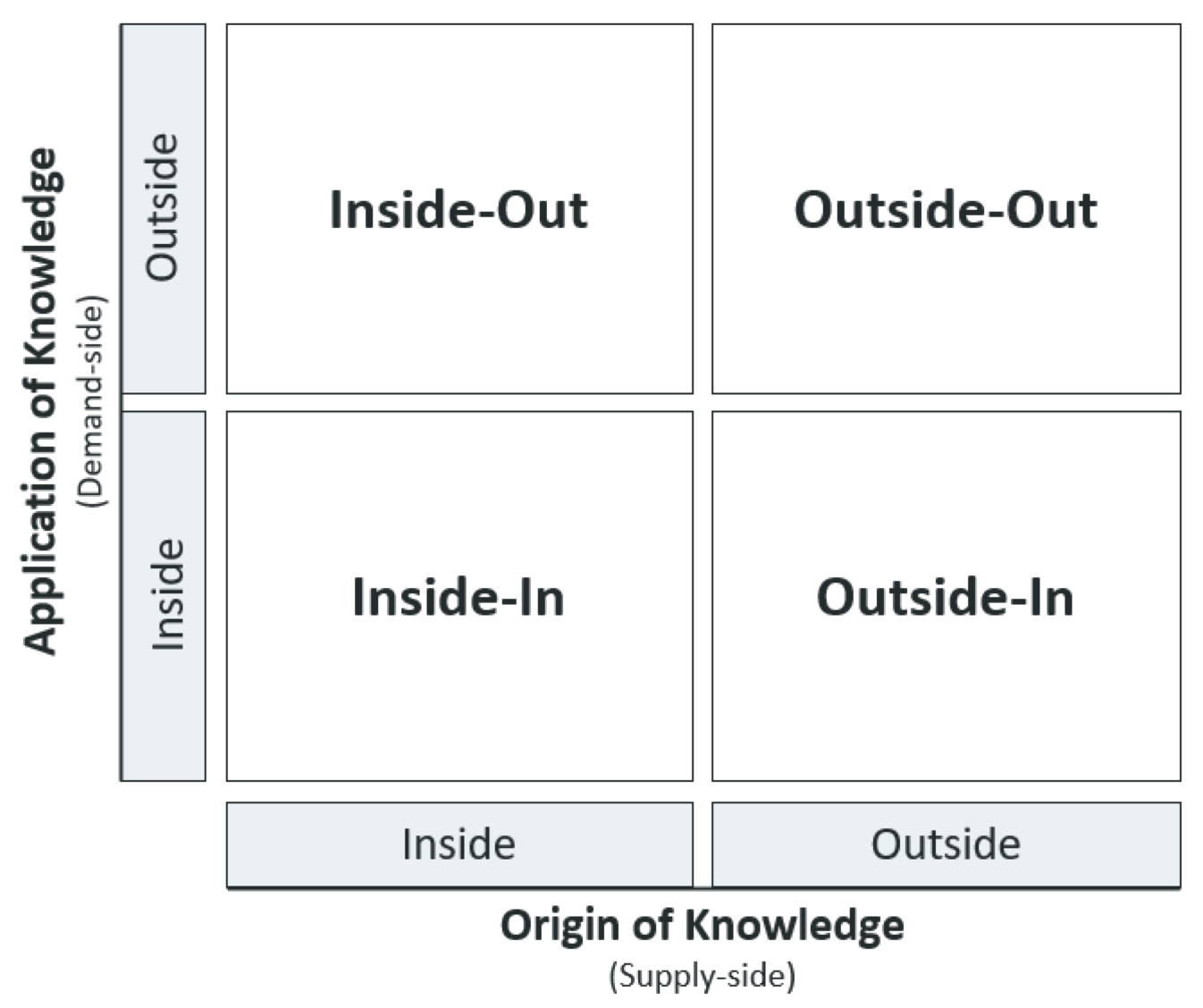

We can introduce our new framework based on this updated view of the Open Innovation Funnel. On the supply side, we look at the origin of knowledge and distinguish between knowledge that originates inside or outside of the corporate boundaries. On the demand side, we look at where knowledge is applied, either inside or outside the corporate boundaries.

Figure 2: Open Innovation – Knowledge Flow Framework

Through our research, we’ve uncovered some practices of CVC units that manage knowledge within and across internal and external boundaries. These include leveraging Outside-In and Inside-Out knowledge flows, as well as Outside-Out and Inside-In knowledge flows, to drive innovation and increase their effectiveness.

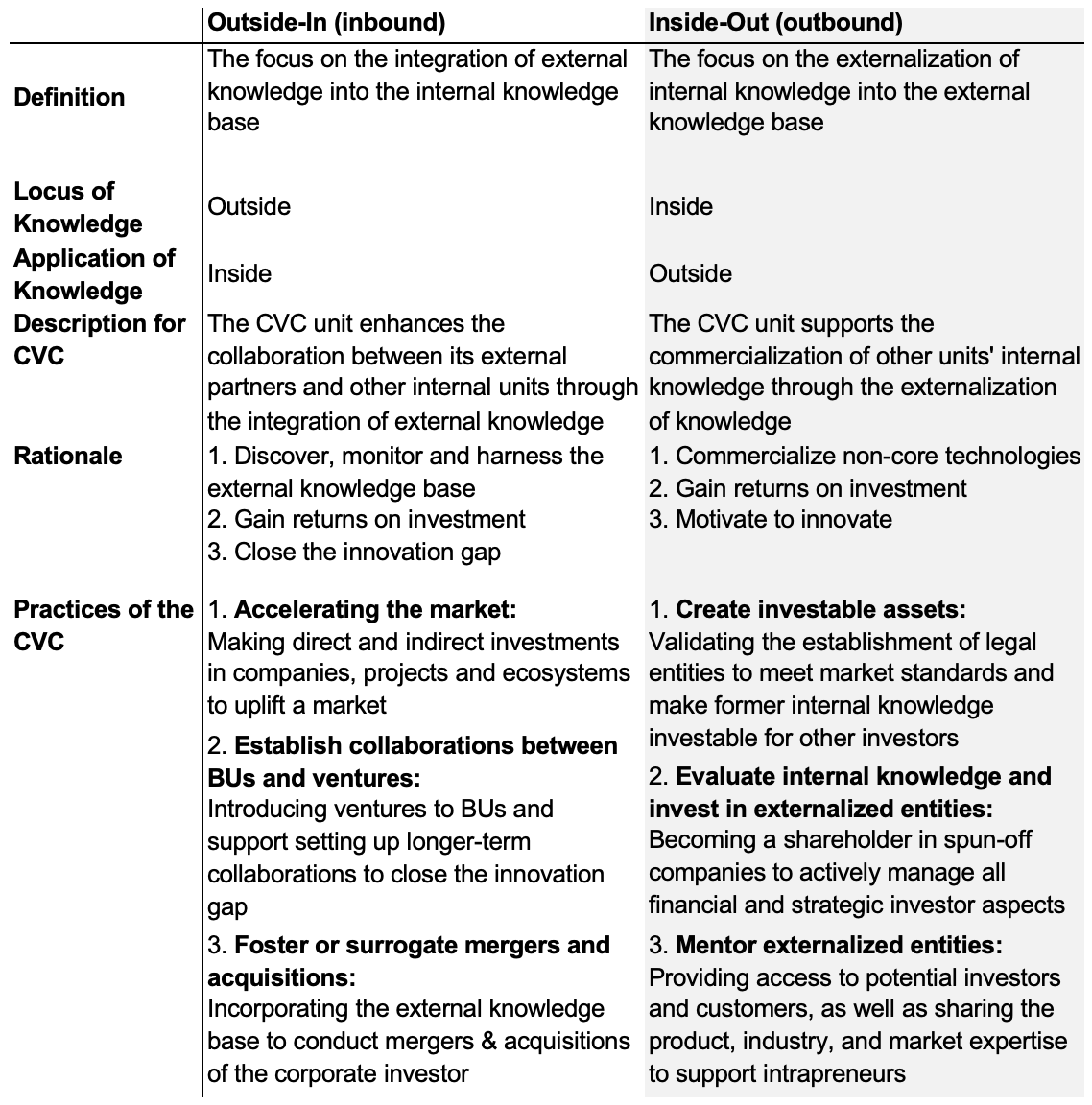

The traditional knowledge flow that CVC focuses on is known as Outside-In. This is already well known, and involves, for instance, accelerating the market through investments in companies, projects, and ecosystems. CVC also works to establish collaborations between businesses and ventures, helping to close the innovation gap. In addition, CVC fosters and surrogates M&A, incorporating external knowledge to support these transactions.

CVC’s role then shifts to Inside-Out, where the focus is on creating investable assets by validating if it makes sense to spin-off a corporate venture. CVC also evaluates internal knowledge and invests in corporate spin-offs. Finally, CVC serves as a mentor to corporate ventures, providing access to investors and customers, as well as sharing industry expertise to support intrapreneurs.

Overall, CVC’s mandate is to support and accelerate innovation by bridging the gap between internal and external knowledge. By investing in companies and providing mentorship and expertise, CVC helps to create a thriving market for innovative ideas.

Now, let’s examine the newly introduced knowledge flows.

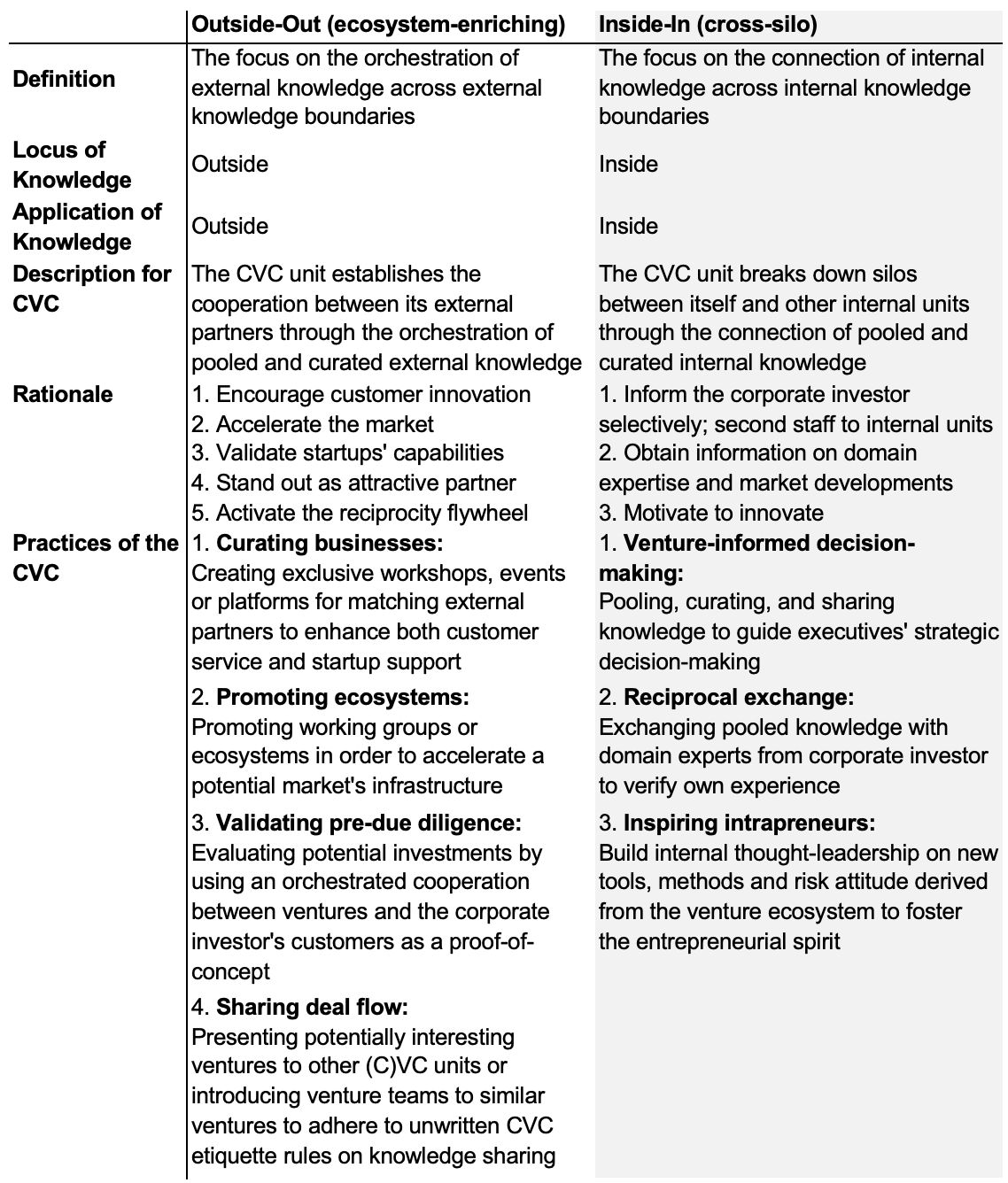

In the Outside-Out model, CVC acts as an Ecosystem Enricher and Shaper, focusing on orchestrating external knowledge across boundaries.

Curating businesses - For instance, SAP.io, BASF Venture Capital, and Hitachi Ventures create exclusive workshops, events, or platforms for matching external partners to enhance both customer service and startup support.

Another practice is promoting ecosystems – which we saw at Hyundai Cradle and their involvement in H2 Mobility. Here, the CVC promotes working groups or ecosystems in order to accelerate a potential market’s infrastructure.

Another practice is validating pre-due diligence – For example, in the case of an anonymized CVC we look at in the paper, where a customer of the corporate mother planned to do a proof of concept (PoC) with a startup the CVC wanted to invest in. To do so, the CVC leveraged the relationship of the mothership with the client, to incorporate the results of that PoC prior to a real due diligence. This saved time and money.

Sharing deal flow - Intel Capital highlighted the importance of sharing interesting ventures with other (C)VC units. This is part of the Venture Capital game and follows kind of a pay-it-forward principle.

At the Inside-In knowledge flow, CVC can be seen as Cross-Silo Knowledge Brokers. Here, the focus lies on connecting internal knowledge across internal knowledge boundaries.

For example, one practice is what we call venture-informed decision-making. Many of the CVCs we investigated were curating and sharing their external venture knowledge to guide the corporate executives’ strategic decision-making. BASF Venture Capital, for instance, is regularly invited to strategy meetings to share their venture insights, that ultimately inform BASF’s corporate (and business unit) strategy.

Another practice from BASF Venture Capital is reciprocal exchange, where CVC managers talk to experts from the business units. They ultimately invested in a company that a colleague from the corporate parent recommended and would have been missed otherwise.

Finally, CVCs can inspire intrapreneurs; for example, Hitachi Ventures established a residency program, in which corporate employees have the opportunity to be mentored by CVC employees and work on real-world valuations and application within the venture world, to ultimately foster the entrepreneurial spirit of the mothership.

To summarize, our new framework for Open Innovation offers a novel approach that can be easily adopted by CVC and Open Innovation managers. By mapping activities onto a 2x2 matrix and identifying gaps, managers can develop a strategic orientation that is tailored to their needs. The 13 actionable practices provide guidance on how to implement new knowledge flows and overcome barriers to increase innovation effectiveness. Overall, this framework offers a valuable tool for companies looking to improve their innovation processes.

Finally, Open Innovation has been defined by Henry Chesbrough and Marcel Bogers as a “distributed innovation process based on purposively managed knowledge flows across organizational boundaries, using pecuniary and non-pecuniary mechanisms in line with the organization’s business model.”3 Our extend framework for Open Innovation builds upon this definition by including inter- and intra-organizational boundaries, as demonstrated in our updated Open Innovation funnel.

Henry W. Chesbrough, Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology (Harvard Business Press, 2003)

Henry W. Chesbrough and Sabine Brunswicker, Managing Open Innovation in Large Firms: Survey Report; Executive Survey on Open Innovation 2013 (Stuttgart: Fraunhofer-Verl., 2013)

Henry Chesbrough and Marcel Bogers, “Explicating Open Innovation: Clarifying an Emerging Paradigm for Understanding Innovation,” New Frontiers in Open Innovation. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014): 3–28.

Insight

Ashley Gambhir et al.

Insight

Ashley Gambhir et al.

Insight

Michele Sharp et al.

Insight

Michele Sharp et al.